Gianduiotto options in America are few. Of those commonly available, most are bad.

Two factors contribute to prevalence of junk gianduiotti on the American market: cost and shelf stability. Bad gianduiotti tend to be cheaper than good. They’re often made by large industrial operators that benefit from economies of scale. Further, price is driven down—along with quality—by skewing the ingredient mix towards inexpensive sugar over more costly cacao solids and hazelnuts. Reducing the hazelnut content and loading the product with sugar also reduce the risk of noticeable oxidation, allowing retailers to keep the product on the shelf much longer.

Before discussing the few rays of light, here are some of the most common, yet least worthy, gianduiotti available in America.

Zàini gianduiotti

The Milan-based company Zàini sells cartons of cheap gianduiotti under the name GianduiOttimi (1). Scanning the ingredient list raises several red flags: leading with sugar (Rule #6), containing aromi (Rule #7), having no disclosure of hazelnut content (Rule #9), and no TGL (Rule #10). From the image on the box, one can see that they’re molded (Rule #2). And, on the box I purchased, no expiration date was to be found (Rule #8). Opening the package releases the harsh smell of sugar and vanillin, not hazelnuts. The molded pieces have none of the softness or velvety texture of good gianduia. Hard, extremely sweet (despite being dark chocolate), and with a foul aftertaste. (The extreme hardness of Zàini’s gianduiotti were demonstrated in a video in Part 28.)

Ferrara gianduiotti are described as a “Product of Italy,” without specifying exactly where. The brand is owned by New Jersey-based Cento Fine Foods, an importer and distributor of a variety of Italian goods. Whatever the provenance, Ferrara shows all the hallmarks of cheap industrial gianduiotti, violating over half of the buying rules (e.g., 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10). The pieces are rock hard, very sweet, with little hazelnut aroma, and with a lingering, unpleasant aftertaste (2).

Perugina began as an artisanal chocolate company in Perugia in the early twentieth century and, with its second generation, became increasingly industrial. (Founder Luisa Spagnoli’s son Mario, whose 1926 manual Fabbricazione del Cioccolato has been cited previously, was largely responsible for that transition.) Today, the company is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Nestlé, which may account for their relatively wide availability in the US. Rule violations abound, as the gianduiotti are molded, lead with sugar, contain artificial flavors, fail to disclose the hazelnut content, do not use TGL, and—with the box I bought—do not come with an expiration date. Though the pieces melt quickly, sugar overwhelms all else, with only vanillin and faint woody hazelnut aromas in the background (3).

Pernigotti is a Piedmont-based company (in Novi Ligure), though industrial and with significant exports. Unlike most of the bad gianduiotti seen in America, Pernigotti products do occasionally appear on non-gourmet supermarket and convenience store shelves within Piedmont. The company makes versions in both milk chocolate (“Classici” or “OroGianduia”) and dark chocolate (“Fondenti” or “NeroGianduia”), though the former is more common in the US. Both versions are molded (Rule #2), lead with sugar (Rule #6), include artificial flavors (Rule #7), fail to disclose hazelnut content (Rule #9), and fail to use Tonda Gentile delle Langhe (Rule #10). The molded pieces are very firm, weak in hazelnut aroma, overly sweet, and can leave a chalky mouthfeel. Though not as bad as the gianduiotti described above, these still aren’t worth eating (4).

At present, only four brands of gianduiotti commonly available in America are close enough to what gianduia should be to warrant recommendation.

Domori gianduiotti

First is Domori. Gianluca Franzoni’s company, located in None (about halfway between Turin and Pinerolo), developed a worldwide reputation for quality on the basis of single-origin bean-to-bar dark chocolate. After Gruppo Illy acquired a majority stake in Domori in 2006, the company began expanding the line from dark chocolate bars to include more “value added” products such as flavored bars, “energy” bars, cross-promotion bundles with other Illy wares, and, recently, gianduiotti.

Domori’s gianduiotti have a lot going from them. They come from one of the world’s most respected chocolate makers. The lack of milk solids makes them one of the few dark chocolate gianduiotti available in the US. They contain no artificial or extraneous ingredients—not even vanilla or soy lecithin. Hazelnut content is high (37%), using Tonda Gentile delle Langhe. They’re even extruded.

Domori (None)

Domori follows all of the “rules” except #6. The ingredient list leads with sugar. Therein lies a problem. Since the gianduiotti have 37% hazelnut content, at least as much sugar, plus a little cocoa butter, it means that the flavor-bearing cacao content is less than 25%. This skews the flavor profile away from chocolate—which one would expect to be Domori’s strength—towards sugar and, secondarily, hazelnut. Many will consider these, as I do, too sweet (5). Still, Domori’s gianduiotti are good enough to merit recommendation, given the options in the US (6).

Baratti & Milano gianduiotti

Second is Baratti & Milano. Though Baratti & Milano’s roots lie in 19th century Turin, Gruppo Elah-Dufour (headquartered in Novi Ligure, Piedmont) bought the company a little over a decade ago. Despite the acquisition, the Baratti & Milano brand continues production in facilities just north of Bra, home of Carlo Petrini and the Slow Food movement.

As an industrial product, Baratti & Milano’s gianduiotti break quite a few of the rules. They’re molded, made with milk chocolate, lead with sugar, contain “aromi,” do not disclose hazelnut content (in the packages I’ve found), and do not claim to contain TGL. Though these factors lower expectations, the gianduiotti easily surpass them. While hazelnut content is undisclosed, it’s high enough to manifest itself in the aroma and flavor. They’re sweet, but not unbearably so. They melt quickly into a smooth mouthfeel, more slick than velvety, but not unpleasant. Sugar and vanillin overstay their welcome on the palate; but there’s no foulness in the aftertaste, as with some of the rubbish previously described. Corner cutting notwithstanding, Baratti & Milano capture enough of what makes gianduia great to earn attention for those in the US (7).

Caffarel gianduiotti (milk chocolate)

Third is Caffarel, a name that will be familiar to those who have followed this series. Caffarel has passed through several changes in ownership, culminating in the acquisition by the Swiss company Lindt & Sprüngli in 1997. Despite Swiss ownership, Caffarel continues to operate in Piedmont—specifically, in Luserna San Giovanni, Paul Caffarel’s birthplace in the Waldensian Val Pellice, to which the company relocated from Turin in 1968.

Though Caffarel makes a respectable dark chocolate gianduiotto (labeled fondente or antica ricetta), their milk chocolate gianduiotti are far more common in the United States. The gold wrapper remains much as it has since the mid-1930s, with the “Gianduia 1865” logo. Caffarel’s gianduiotti comply with most of the “rules,” including the use of extrusion rather than molding. Hazelnut content is a reasonable 28%, though not TGL. The ingredient list leads with sugar, but the significant hazelnut content and balance of other ingredients avoids the fault of oversweetness. The use of vanillin is unfortunate, as is the unnecessary inclusion of a small amount of almonds (8).

Caffarel (Luserna San Giovanni)

Extrusion and meaningful hazelnut content leave Caffarel’s gianduiotti firm, but with some give when squeezed. They melt quickly into a tongue-coating, velvety texture. Though sweet overall, the hazelnuts and milk chocolate are well balanced. Though Caffarel’s gianduiotti cannot stand shoulder to shoulder with the best of Piedmont, they are a fair representation of gianduia for those who’ve never tasted it (9).

Venchi gianduiotti

The best gianduiotti readily available in the US at present are from Venchi. The Piedmontese company bears the name of Silvano Venchi, who opened for business in Turin in 1878; however, through a series of mergers, Venchi also continues the legacy of UNICA, Cuba, Dora Biscuits, and such early masters of gianduia as Moriondo & Gariglio and Talmone (10). Though too large to be considered an artisanal operation, Venchi’s factory remains fairly small for a chocolate company, occupying one modest building in Castelletto Stura, outside of Cuneo.

Venchi gianduiotti ripieni

Venchi’s only deviations from the “rules” are in molding (rather than extruding or hand-cutting) and in the failure to offer traditional dark chocolate gianduiotti (though gianduia fondente does appear elsewhere in their product line). The ingredient list leads with hazelnuts, at 30%. Tonda Gentile delle Langhe. Natural vanilla. The fragrance of hazelnuts emerges even before unwrapping a gianduiotto. Though molded, the hazelnut content is high enough to leave the gianduia soft. Texture is very smooth. Hazelnut sweetness predominates. The chocolate has a slightly caramelized milkiness. While one can find better in Piedmont, Venchi’s gianduiotti are nothing to sneeze at even there, especially in an apples-to-apples comparison with other milk chocolate versions (11).

Though Venchi doesn’t currently make a dark chocolate gianduiotto, they do have “gianduiotti ripieni” (i.e., filled gianduiotti) (12). With these, the gianduiotti molds are coated with a thin layer of dark chocolate, before being filled with gianduia. In addition to offsetting the gianduia’s sweetness, the dark chocolate shell melts more slowly than the gianduia filling, making for a pleasant and addictive textural contrast. While a few Piedmontese makers do gianduiotti ripieni (most notably Silvio Bessone in Vicoforte), I have yet to find any better than Venchi’s (13).

Venchi (Castelleto Stura)

Notes:

1. Ingredients listed (Zàini): Sugar, hazelnuts, cacao mass, cocoa butter, soy lecithin, flavorings.

2. The one-letter difference between this brand name and that of Ferrero could easily create brand confusion. Surely that’s mere coincidence. Ingredients listed (Ferrera): Sugar, hazelnuts (22%), cacao mass, cocoa butter, powdered whole milk, soy lecithin, flavorings.

3. Ingredients listed (Perugina): Sugar, hazelnuts, chocolate, cocoa butter, soy lecithin, artificial flavors.

4. Ingredients listed (Pernigotti, OroGianduia): Sugar, hazelnuts, cacao mass, cocoa butter, powdered whole milk, soy lecithin, flavorings.

5. Intense sweetness is not foreign to tradition. In fact, compared to recipes published by Spagnoli (1926) and Kemeny (1949), Domori’s gianduiotti are lower in sugar and cocoa butter, while higher in hazelnuts and cacao liquor.

6. Ingredients listed (Domori): Sugar, Piedmont hazelnuts PGI (37%), cacao mass, cocoa butter.

7. Ingredients listed (Baratti & Milano): Sugar, hazelnuts, cacao mass, cocoa butter, whole milk powder, soy lecithin, flavorings. Baratti & Milano’s parent company also produces gianduiotti in Piedmont under the Novi brand name. The ingredient list for Novi gianduiotti is identical to that for Baratti & Milano, except that it specifies the hazelnut content of 26%.

8. See Rule #7 and Note #10 in Part 28.

9. Ingredients listed (Caffarel): Sugar, hazelnuts (28%), cacao mass, powdered whole milk, cocoa butter, almonds, vanillin.

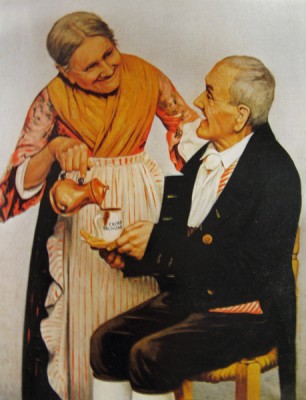

Talmone/Venchi, “Cacao Due Vecchi”

10. Venchi continues to use Talmone’s iconic marketing piece featuring Ochsner’s 1890 illustration, Due Vecchi. It’s a pity that Venchi has abandoned the Talmone brand name, since: (i) Talmone was in business 28 years before Venchi; (ii) Talmone was a Waldensian company; (iii) Talmone was, first and foremost, a chocolate company (while Venchi was best known for caramels); (iv) whether or not Talmone invented gianduia (a hypothesis set forth in Part 13), the company was at the forefront of gianduia through the closing decades of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth; and (v) Talmone (especially in its second generation) set trends in product development and marketing that continue today.

11. Ingredients listed (Venchi, Gianduiotti): Piedmont hazelnut paste PGI (30%), sugar, cocoa butter, cacao mass, whole powdered milk, soy lecithin, natural vanilla flavor.

12. Ingredients listed (Venchi, Gianduiotti Ripieni): Sugar, Piedmont hazelnut paste PGI (20%), cacao mass, cocoa butter, whole powdered milk, soy lecithin, natural vanilla flavor.

Bloom from fat migration in Venchi gianduiotti ripieni

13. There is one quirk to be aware of, when buying and consuming gianduiotti ripieni (from Venchi or anyone else): fat bloom due to fat migration. When the liquid fat (i.e., hazelnut oil) from the gianduia filling makes contact with the solid fat (i.e., cocoa butter) in the dark chocolate shell, the fat phase gradually moves towards equilibrium, with the solid fat moving inwards and liquid fat moving outwards. When the liquid fat approaches the dark chocolate surface, it can carry cocoa butter along with it, which will crystallize on the surface (i.e., fat bloom). With enough time, the movement of fat can soften the shell and firm up the center, though you’ll usually have eaten the gianduiotti before they reach that point. In any event, the white, chalky substance that you see in the photo above is fat bloom—not “mold” or anything that should keep you from eating the piece.