This week, we return to the myth of the early nineteenth century invention of gianduia. The setting of the story—the Continental System and its impact on industry and individuals—can be easily established. Yet there are no known contemporary sources describing gianduia or a gianduia-like substance in Piedmont during the six years between the Berlin Decree and the de facto collapse of the Continental System in the summer of 1812 when Russia and England made peace with the Treaty of Örebro.

Like Lupini for Chocolate?

The only contemporary source for a chocolate surrogate, identified by Gigi and Clara Padovani, is an 1813 booklet by Antonio Bazzarini, Piano Teorico-pratico di Sostituzione Nazionale al Cioccolato (i.e., Theoretic-practical Plan for National Substitution of Chocolate). Bazzarini noted the high cost of chocolate at the time and, indeed, proposed a substitute using more economical and locally common ingredients.

However, Bazzarini published his booklet in Venice (Veneto), not in Piedmont. Bazzarini’s recipe did not include hazelnuts at all, but combined (in descending order by weight) well-roasted almonds, sugar, cornmeal, toasted and ground lupini, cinnamon, and vanilla (1). Furthermore, there is no reason to believe that the young Istrian’s concoction ever caught on in Venice or surrounding regions, let alone in Piedmont, thus undercutting any potential claim of a chain of influence with the subsequent invention of gianduia.

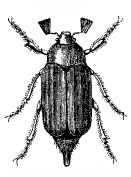

May Bug (from The Microscope: Its History, Construction, and Application; Jabez Hogg, 1861)

Some authors claim that the Continental System saw the invention, not of gianduia itself, but of a conceptual forerunner known in the Piedmontese dialect as givo (2). Givo is Piedmontese for a beetle (specifically, Melolontha melolontha L., or the May bug), used figuratively to mean a “cigar butt.” The figurative usage was further extended to reflect the presumed shape of a stubby confection consisting of chocolate and, according to some modern authors, bits of hazelnut.

As is the case with gianduia, however, there are no extant early nineteenth century sources describing givo as a confection. The earliest source describing such a thing—and the one on which most authors rely (directly or, more often, indirectly)—was a booklet (Il Cioccolato ed il Suo Valore Alimentare) published in 1933, more than a century after the supposed invention (3).

Addressing the limitations of that booklet at this point would take us unnecessarily into the weeds (4). For now, it suffices to note that the booklet does not provide any source for the claim and that it relies extensively on secondary sources—particularly a series of trade magazine articles by A. Cagliano published in 1932—that did not even claim that givo existed in the early 1800s (5). More importantly, neither Cagliano nor Il Cioccolato ed il Suo Valore Alimentare assert that givo contained hazelnuts. That claim appears to be an elaboration by more recent authors, probably conflating the early nineteenth century givo described in Il Cioccolato ed il Suo Valore Alimentare with a product called by the same name in the mid-1860s (about which, more later) (6).

Vocabolario Piemontese-Italiano (Michele Ponza, 1877)

Absence of early documentary evidence raises doubt about claims that early nineteenth century givo were a forerunner of gianduia. Examination of nineteenth century Piedmontese and Piedmontese-Italian dictionaries deepens that doubt. From 1815 to 1893, whenever authors of dictionaries and glossaries defined givo, the term referred primarily to a beetle and, in later years, a cigar butt (7). Twentieth century Piedmontese and Piedmontese-Italian dictionaries also fail to mention a chocolate-related meaning for givo (8). Camillo Brero’s multi-volume Dissionari Piemontèis includes both established meanings of givo, as well as five Piedmontese idioms employing the word, none of which have anything to do with chocolate (9).

May Bug (from Dr. Schlich's Manual of Forestry, Vol. IV, 1895)

Since the authors of dictionaries, glossaries, and lexicons over the course of two centuries have consistently failed to recognize givo as a confection, it appears that it either was not one or, perhaps, was so rare or obscure as to escape notice.

At present, the historical record provides no credible evidence for the production of a gianduia-like substance in early nineteenth century Piedmont.

Notes:

1. Padovani, Gigi, and Clara Padovani. Gianduiotto Mania — La Via Italiana al Cioccolato: Storia, Fortuna, Ricette. Giunti, 2007. Pp. 31-4.

2. Marsero, Mario. Dolci, Delizie Subalpine: Piccola Storia dell’Arte Dolciaria a Torino e in Piemonte. Lindau. Turin. 1995. P. 73.

3. “Il Cioccolato ed il Suo Valore Alimentare,” Rivista Semestrale di Studi Economici e Tecnici, Anno 1, n. 3. Edited by the Federazione Nazionale Fascista dell’Industria Dolciaria. Turin. November, 1933. P. 20.

4. Don’t worry, though. We’ll be neck-deep in those weeds in time.

5. Cagliano, A. “Frammenti di Storia del Cacao e del Cioccolato con Particolari Cenni all’Italia e Torino.” Il Dolce: Rivista delle Industrie Italiane del Cioccolato, Biscotti, Caramelle, Confetture ed Affini. No. 72, February 1932. The specificity of the claim in “Il Cioccolato ed il Suo Valore Alimentare” suggests that the author did have some source in mind, referencing production in Turin of 350 kilograms of givo in 1802.

6. The author of “Il Cioccolato ed il Suo Valore Alimentare” refers to givo as the “ancestor” of the product improved and perfected by Michele Prochet and named “Gianduia” in 1867, but without describing any connection other than the shared name (p. 20). The failure to say anything about hazelnut content in early nineteenth century givo does not mean that the anonymous author denies the existence of a gianduia-like product before the mid-nineteenth century. On the contrary, he inaccurately claims that Piedmontese chocolate makers were making bars of hazelnut chocolate as early as the 1600s (p. 19).

7. Zalli, Casimiro. Disionari Piemontèis, Italian, Latin e Fransèis (Volume 1). Peder Barbiè. Carmagnola. 1815. See also, Zalli, Casimiro. Dizionario Piemontese, Italiano, Latino, e Francese (Volume 1). Second Edition. Pietro Barbiè. Carmagnola. 1830. See also, Sant’Albino, Vittorio di. Gran Dizionario Piemontese-Italiano. Societá L’Unione Tipografico-Editrice. Turin. 1859. See also, Ponza, Michele. Vocabolario Piemontese-Italiano. Ninth Edition. G. Lobetti-Bodoni. Pinerolo. 1877. See also, Rosa, Ugo. Glossario Storico Popolare Piemontese. Ermanno Loescher di Carlo Clausen. Turin. 1889. See also, Dal Pozzo, Giuseppe. Glossario Etimologico Piemontese. Second Edition. F. Casanova. Turin. 1893.

8. Levi, Attilio. Dizionario Etimologico del Dialetto Piemontese. G.B. Paravia & C. Turin. 1927. See also, Brero, Camillo. Dissionari Piemontèis (G-N). Ij Brandé. Turin. 1974. See also, Brero, Camillo. Vocabolario Piemontese Italiano. Editrice Piemonte in Bancarella. Turin. 1982.

9. Brero (1974), 407.