No discussion of gianduia would be complete without consideration of Ferrero SpA and its flagship product, Nutella. Though a detailed examination of the company and its products is beyond the scope of this series, a brief historical sketch will suffice as background for some more specific observations to come.

Pietro Ferrero was born on September 2, 1898, in Farigliano, a small agricultural community on the western fringe of the Langhe. Determined not to work the land, Ferrero left Farigliano for Dogliani (less than two miles away) where he apprenticed in a bakery. In 1923, he opened his own pastry shop in Dogliani. One year later, he married Piera Cillario, and the couple’s only child, Michele Ferrero, was born on April 26, 1925 (1).

Pietro Ferrero was born on September 2, 1898, in Farigliano, a small agricultural community on the western fringe of the Langhe. Determined not to work the land, Ferrero left Farigliano for Dogliani (less than two miles away) where he apprenticed in a bakery. In 1923, he opened his own pastry shop in Dogliani. One year later, he married Piera Cillario, and the couple’s only child, Michele Ferrero, was born on April 26, 1925 (1).

Ferrero relocated to Alba in 1926 and built a fairly successful business over the following years, before trying his luck in Turin with a small pastry shop near Porta Nuova in 1934. After two years of struggle, Pietro Ferrero left Turin to seek opportunity in Asmara, Eritrea, hoping to sell bread and pastries to Italian colonists and troops after Mussolini ordered the invasion of Abyssinia. Finding little to gain in Africa, Ferrero returned to Italy and opened a new and larger pastry shop in Turin in 1940. Italy entered the war in June and, by the end of the month, the first RAF bombs began falling over Turin. Pietro Ferrero and his family promptly fled Turin, returning to Alba to open yet another pastry shop (2).

Dogliani, Italy

As Italy’s fortunes in the war continued to decline and poverty, food shortages, and supply disruptions increased, Pietro Ferrero set to work developing a new, inexpensive sweet to broaden his market. Roughly imitating gianduiotti (which were still strictly a luxury good), Ferrero combined roasted hazelnuts, almonds, sugar (or, failing that, molasses), cocoa powder, and vegetable fat (3). Driving down the quantity of cacao solids reduced the cost, so that the product could be sold for less than one-fourth the price of chocolate. In a 1966 interview, Michele Ferrero referred to his father’s invention as “a pastone [i.e., mish-mash], a kind of gianduiotti, that was very good, but that cost little” (4).

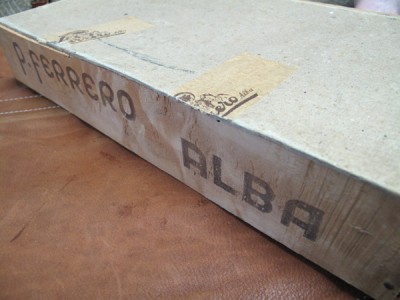

Early 1950s Giandujot box

Nearly a year after V-E Day, Pietro Ferrero’s small Alba factory released over six-hundred pounds of the pastone on the market, under the name Giandujot—Piedmontese for gianduiotto, the diminutive of Gianduia (5). Ferrero’s Giandujot was sold in slabs and loaves, wrapped in green and gold foil, intended to be sliced and eaten on bread as an energizing afternoon snack (merenda) (6). Consistent with its name, Giandujot was marketed with an illustration of Gianduia throwing his arms around two young children, an image that remained central to the company’s branding until the mid-1950s.

Ferrero distribution truck

Giandujot succeeded immediately and beyond all expectation. By the end of 1946 (the year in which it was released, in late spring), Ferrero had grown from a dozen employees to fifty and had produced over one hundred tons of Giandujot. The following year, Ferrero doubled his workforce and produced over 2,500 tons of Giandujot (7). Competitors took note. Mario Spagnoli, Technical Director of Perugina, marched into a board meeting carrying a package of Ferrero’s Giandujot and presented it to the members, announcing, “This is the future of confectionery” (8).

Outgrowing the small factory in the city center, Ferrero moved to a location west of the city on the banks of the Tanaro river. This decision nearly proved to be his undoing. On September 4, 1948, heavy rains in the Langhe fed the Talloria torrent that flowed into the Tanaro, flooding the surrounding plains. Water and mud rose in Ferrero’s factory above shoulder-height, sparing no part. Tremendous effort from Pietro Ferrero and his employees enabled partial resumption of production in under a week. The strain took a toll, however, and less than six months after the flood, Pietro Ferrero suffered a massive heart attack, dying at the age of fifty-one (9).

Notes:

1. Padovani, Gigi. Nutella: Un Mito Italiano. Rizzoli. Milan. 2004. Pp. 43-4. The basics of Ferrero history can be found in several sources (e.g., Ferrero 1946-1996: Un’Industria Attraverso Mezzo Secolo di Storia e di Costume, Turin 1996; Storia di un Successo: Ferrero la Più Grande Azienda Dolciaria del Mec, Turin 1967), though most are written for popular audiences and generally express the company’s official story. Padovani’s books (i.e., Nutella: Un Mito Italiano; Gnam! Storia Sociale della Nutella; and, with Clara Vada Padovani, Passione Nutella) are no exception. (Anyone attempting a critical history of Ferrero has his work cut out for him. The Ferrero family’s secrecy rivals that of John and Forrest Mars, Jr.)

2. Subbrero, Giancarlo. “La Ferrero di Alba: Appunti per un Profilo Storico,” in Il Cioccolato: Industria, Mercato e Società in Italia e Svizzera (XVIII-XX Sec.). FrancoAngeli. Milan. 2007. P. 154-5. Life, Vol. 8, No. 26. June 24, 1940. P. 30.

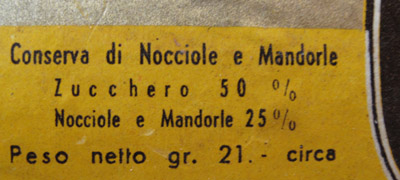

Ingredient description from early 1950s Giandujot box

3. Though the inclusion of almonds in Giandujot receives no mention in prior publications describing the product, extant labels from the early 1950s plainly state that they are an ingredient. In fact, at that time, the product was marketed as a “conserva di nocciole e mandorle” (i.e., hazelnut and almond jam/preserves). Padovani identifies the vegetable fat (i.e., the cocoa butter replacement) as coconut oil. Though he does not specify, it seems likely that the coconut oil (if that was indeed the fat Ferrero initially used) was hydrogenated, so the product would remain solid through a wider temperature range.

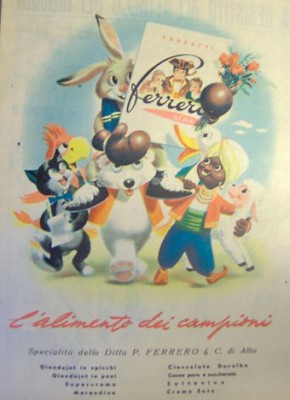

Ferrero promotional material from 1950s

4. Padovani, 47.

5. See Part 12.

6. Though most writers only refer to the distribution of loaves of Giandujot, Ferrero marketing materials from the 1950s also describe “Giandujot in spicchi,” or “wedges of Giandujot,” indicating that it was also sold in the traditional shape of gianduiotti.

7. Subbero, 155. See also, Padovani, 49.

8. Others at Perugina did not share Spagnoli’s enthusiasm. At that time, the company still maintained a reputation for high quality chocolate products. Many believed that emulating Ferrero would damage the Perugina brand. Perugina officials also felt incapable of duplicating Ferrero’s unique distribution system, not only placing products on shelves, but contracting with grocers and shopkeepers to cut and sell Giandujot by the slice. Buitoni, Bruno. Pasta e Cioccolato: Una Storia Imprenditoriale (intervista di Giampaolo Gallo). Casa Editrice Protagon. Perugia. 1992. Pp. 86-7.

9. Padovani, 50-1.