At present, national and online retailers offer few brands of gianduia to American consumers. Those fortunate enough to live near a good Italian market may have somewhat better options. Though we’ll discuss some of the more common brands shortly, limited and inconsistent availability make it difficult to advise on what to buy. Instead, let’s discuss how to buy (1).

Gianduia Bars

Rule #1: Buy gianduia as gianduiotti, not in bar form. Gianduiotti were the enduring invention of the Waldenses, the pride of Turin, and the namesake of Gianduia in the nineteenth century, historically preceding gianduia bars (tavolette) in Italy. Such historical originality warrants the respect of traditionalists. The size and shape of gianduiotti deliver a perfect, individually-wrapped, bite-sized portion, offering convenience, without overwhelming.

However, the real reason gianduiotti are preferable to bars lies in their differing composition. The high hazelnut content of gianduia paste makes it soft and somewhat tacky, unsuitable for molding. Molding bars with clean lines and enough firmness and rigidity to hold their form requires adaptation of the traditional formula. Specifically, it necessitates lowering the proportion of hazelnut (with its liquid-at-room-temperature oil) and adding cocoa butter (which is solid at room temperature and only melts completely a little below body temperature). Doing this undercuts several of gianduia’s greatest strengths: the intensity of hazelnut aroma, the soft, velvety texture, and the rapid melt and distribution of flavor from high hazelnut oil content. And in exchange for what? Improved shelf-stability? It’s just not worth it.

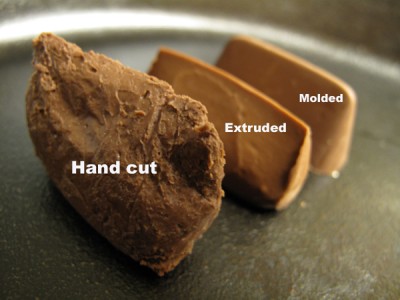

Rule #2: Seek hand-cut over extruded, and extruded over molded. When picking up a hand-cut gianduiotto—feeling its heft, its wedge-like shape, and the thick, crinkled foil in which it has been hand-wrapped—it is hard to avoid romanticism about this original method of formation that prevailed for nearly half a century. But romanticism is not the only reason to prefer hand-cut gianduiotti over extruded. Give the foil-wrapped gianduiotto a gentle squeeze and it yields to the pressure. Working by hand, makers can incorporate a greater percentage of roasted hazelnuts—as high as 40%. This results in a softer texture and more powerful hazelnut aroma than one finds in most extruded gianduiotti. Hand-cut gianduiotti are not currently made or imported for retail in America. Sadly, they’re uncommon even in Piedmont. Yet they are well worth the seeking.

Extrusion allows for a respectable percentage of hazelnut, usually no higher than 33%. Though not as soft as hand-cut, they are, on average, noticeably softer than molded gianduiotti. The traditional trio of ingredients can be balanced without concern for how the resulting paste may stick to a mold (2). Not all extruded gianduiotti are equal, but most are of acceptable quality and some are among the best made.

Extrusion allows for a respectable percentage of hazelnut, usually no higher than 33%. Though not as soft as hand-cut, they are, on average, noticeably softer than molded gianduiotti. The traditional trio of ingredients can be balanced without concern for how the resulting paste may stick to a mold (2). Not all extruded gianduiotti are equal, but most are of acceptable quality and some are among the best made.

The gap widens between molded gianduiotti and those made with the older methods, for the reasons described in Rule #1. The method requires a shift in the fat proportions so the pieces will release from the molds. They’re slicker, harder, and slower to melt on the tongue. While some artisanal shops in Piedmont mold by hand (with better or worse results), most molded gianduiotti are mechanically produced by industrial firms, which often compromise in other ways, as well (3). Watch the video above to see how dramatically molded, extruded, and hand-cut gianduiotti differ in hardness.

Rule #3: Buy from gianduia specialists. From its origins, gianduia was the product of chocolate makers—individuals and companies that transform dried cacao into finished chocolate. Today, most small shops in Piedmont work from couverture or from cacao liquor, rather than from the bean (4). Even so, they depend on common chocolate-making equipment to transform cacao mass, sugar, and hazelnuts into gianduia, including mélangeurs, roll refiners, and conches. With dedicated chocolate-making equipment, gianduia makers can produce a paste with smaller, more uniform particle size and more thorough coating of particles with fat—smooth, velvety, homogenous.

Rule #3: Buy from gianduia specialists. From its origins, gianduia was the product of chocolate makers—individuals and companies that transform dried cacao into finished chocolate. Today, most small shops in Piedmont work from couverture or from cacao liquor, rather than from the bean (4). Even so, they depend on common chocolate-making equipment to transform cacao mass, sugar, and hazelnuts into gianduia, including mélangeurs, roll refiners, and conches. With dedicated chocolate-making equipment, gianduia makers can produce a paste with smaller, more uniform particle size and more thorough coating of particles with fat—smooth, velvety, homogenous.

The reduction of particle size and homogenization of fats and nonfat solids made possible with chocolate-making equipment cannot be duplicated, and only poorly approximated, with the tools available to most small chocolatiers. Hazelnut praliné is not gianduia. Chocolate with chopped hazelnuts is not gianduia. The “flavor combination” of chocolate and hazelnuts is not gianduia. While we can hope that one of America’s talented small-batch chocolate makers will someday produce quality gianduia domestically, for now it must be sought from gianduia specialists in western Europe (and mainly Italy).

Extruded gianduiotto fondente by Caffarel (Luserna San Giovanni)

Rule #4: Remember gianduia’s dark past. Gianduia began as a dark chocolate product and remained exclusively so for at least a third of its history. Though most of the world knows gianduia in its milk chocolate form (to the extent they know it at all), gianduia fondente remains common in Piedmont. Beyond its historical primacy, many prefer dark chocolate gianduia for its cleaner flavor (absent milk’s sugars, proteins, and fats) and greater balance between bitterness and sweetness. Milk chocolate gianduia can be excellent; but most chocolate connoisseurs are likely to prefer the more traditional form.

Rule #5: Mind the cacao solids. In inspecting the ingredient list, look for gianduia made with cacao liquor (or mass or paste). While a bit of additional cocoa butter may be acceptable (or even necessary, for molded gianduiotti and bars), products that substitute cocoa powder and cocoa butter for cacao liquor should be avoided. It should go without saying that products containing “cocoa butter equivalents” or CBEs—industrial Newspeak for inexpensive vegetable fats used in place of cocoa butter—are best left on the shelf.

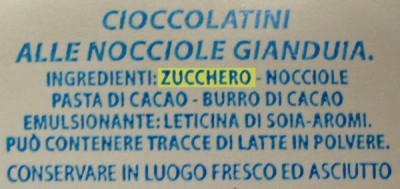

Rule #6: Beware those that lead with sugar. European labeling regulations, like those in the United States, require that ingredients be listed in descending order of weight. When reviewing the ingredient list, pay special attention to the leading ingredient. Sugar is cheaper than good cacao or hazelnuts, so many industrial producers use huge amounts of it. Under the current definitions in the Codex Alimentarius, a product could be nearly 50% sugar by weight and still be called gianduia (5). Sugar-heavy gianduiotti can be quite unpleasant—weak in hazelnut aroma, tacky (rather than velvety) in texture, and with poor melt characteristics.

Rule #6: Beware those that lead with sugar. European labeling regulations, like those in the United States, require that ingredients be listed in descending order of weight. When reviewing the ingredient list, pay special attention to the leading ingredient. Sugar is cheaper than good cacao or hazelnuts, so many industrial producers use huge amounts of it. Under the current definitions in the Codex Alimentarius, a product could be nearly 50% sugar by weight and still be called gianduia (5). Sugar-heavy gianduiotti can be quite unpleasant—weak in hazelnut aroma, tacky (rather than velvety) in texture, and with poor melt characteristics.

Sugar leading the ingredient list needn’t always be a deal-killer. You just have to do the math to estimate how much sugar is in there. For products made in Europe, the percentage of hazelnuts by weight will usually be included in the ingredient list. If a sugar-leading gianduia contains 37% hazelnuts, it has over 37% sugar. Best case scenario, it’s going to be quite sweet (though perhaps not overwhelmingly so), with strong hazelnut aroma (assuming TGL are used), and more subdued chocolate flavor (especially if it’s a milk chocolate gianduia, since a portion of the remainder will be dry milk solids). If you don’t mind gianduia with that profile, it might be worth a try.

Let’s pause for a brief, related comment. Gianduia is sweet. Not necessarily overwhelmingly sweet—and, on average, less sweet than what passes for chocolate in most supermarkets and convenience stores in America and Europe—but sweet, nonetheless. Not only is gianduia sweet, but it should be sweet. It arrived at a time when sugar was a prized luxury, rather than a constituent of every food product sold to every socioeconomic class. It developed, as did the companies that made it, alongside the expanding Italian beet sugar industry, turning a rare, seasonal extravagance into an affordable, popular product by the mid-twentieth century. Gianduia’s sweetness is unlikely to be a turnoff for most chocolate lovers, except in the extreme cases covered by Rule #6. But if you’re the kind of chocolate snob who dims the lights, closes his eyes, and meditates on Le 100% or Noir Infini, you’ve come to the wrong shop.

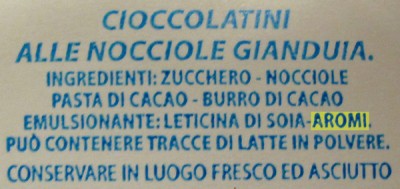

Rule #7: Avoid extraneous ingredients. Cacao liquor, roasted hazelnuts, and sugar (cane or beet) are sine quibus non. Though optional, milk solids, natural vanilla (vaniglia), and lecithin are also acceptable (6). If there’s anything else on the ingredient list, you should probably move on.

Rule #7: Avoid extraneous ingredients. Cacao liquor, roasted hazelnuts, and sugar (cane or beet) are sine quibus non. Though optional, milk solids, natural vanilla (vaniglia), and lecithin are also acceptable (6). If there’s anything else on the ingredient list, you should probably move on.

What else might turn up that would lead you to walk away? Vegetable fats other than cocoa butter or hazelnut oil. Vanillin (vanillina). Italian labeling regulations also allow vanillin to be included under the catch-all term “aromi” (with “aromi naturali” reserved for natural flavorings). Though blessedly rare, “diet” gianduiotti with artificial sweeteners have appeared on the market (7).

Some gianduia may include one gray area ingredient: almonds (mandorle). This is not common in Piedmont and may even be unique to Caffarel. Almonds are not foreign to Piedmontese culinary tradition. Though not as common as hazelnuts or chestnuts in the region, sweet and bitter almonds are used in a number of definitive local sweets and pastries, including ossa di morto, baci di dama, and of course amaretti. Long before gianduia’s invention, Spanish and Mexican chocolate makers frequently ground almonds (in modest proportions) with cacao, though for use in beverage form. With the spread of gianduia in the late nineteenth century, it would be natural for some makers to use almonds as a supplement or even substitute for hazelnuts, particularly in countries with little or no domestic supply of hazelnuts (e.g., France, Switzerland, Germany, et al.). Today, the Codex Alimentarius allows the inclusion of other nuts in gianduia, as long as the minimum hazelnut and cacao solid percentages are met and the total nut content does not exceed 60%. (Under that permissive standard, one could market as “gianduia” a product with 40% peanuts, 32% cacao solids, 20% hazelnuts, and 8% sugar, which is sheer lunacy.)

With that said, surviving descriptions of the earliest gianduia make no mention of almonds—only hazelnuts. While the combination of almonds with chocolate was common enough to merit mention in Mario Spagnoli’s 1926 manual Fabbricazione del Cioccolato, the author clearly distinguishes the product from gianduia by using the name cioccolato alla mandorla (i.e., almond chocolate). He describes gianduia as containing nothing other than hazelnuts, sugar, and cacao solids, and gianduiotti as being made exclusively in Italy (8). Definitions of gianduia in nineteenth and twentieth century Italian dictionaries mention no nut other than hazelnuts.

Today, artisanal and quality-oriented makers—even most industrial makers—in Piedmont use hazelnuts, and only hazelnuts, in gianduia (9). From a traditional perspective, almonds simply do not belong in gianduia. Whether Caffarel should be given a pass on this is debatable (10).

Rule #8: Check the date. Hazelnuts go rancid. Don’t buy product that’s near or past its “use by” or “best before” date. If you’re ordering online, ask the vendor for the expiration date before completing the order. Any retailer worth doing business with will happily tell you. Retard oxidation by storing gianduia in an airtight container in a cool, dark, and dry place. In recent years, some makers have begun including the harvest year of the hazelnuts in the ingredient list, offering another way of ensuring the hazelnuts are not past their prime.

Rule #9: Examine the hazelnut content. Hazelnuts are the heart of gianduia. If a maker is skimping, sliding by with the minimum necessary to call the product “gianduia” (i.e., 20% in Europe, though the term is unregulated in the US), move on. Quality makers have pride in their product and generally disclose the hazelnut content in the ingredient list by percentage weight. If the hazelnut content isn’t stated, there’s a good chance the product isn’t worth the cash or calories (11). Generally speaking, gianduia with less than one-third hazelnut content will be weak in aroma and the hazelnut flavor will be muted by the sugar or chocolate. Low hazelnut content also contributes to the rock-hard texture found in the many of the worst industrial gianduiotti (as seen in the video above).

More is not necessarily better. Ideally, gianduia strikes a synergistic balance between the ingredients, with no one dominating the others. Depending on the balance and quality of ingredients, a gianduiotto with 33% hazelnut content could well be better than one with 36%. Because of the need to keep gianduia solid at room temperature, it’s difficult to push the hazelnut content higher than 40% without compromising the traditional taste and texture.

![]() In addition to the quantity of hazelnut content, consider the form. Gianduia makers have long considered the roasting of hazelnuts to be a delicate art, crucial to the development of flavor and aroma in the final product. Rather than roasting hazelnuts in-house, some makers (often industrial firms) purchase hazelnut paste (pasta di nocciole). This entrusts the roasting to a third party, which an artisanal gianduia maker would be loathe to do, just as a truly artisanal chocolate maker would never outsource the roasting of cacao to third-party personnel and facilities.

In addition to the quantity of hazelnut content, consider the form. Gianduia makers have long considered the roasting of hazelnuts to be a delicate art, crucial to the development of flavor and aroma in the final product. Rather than roasting hazelnuts in-house, some makers (often industrial firms) purchase hazelnut paste (pasta di nocciole). This entrusts the roasting to a third party, which an artisanal gianduia maker would be loathe to do, just as a truly artisanal chocolate maker would never outsource the roasting of cacao to third-party personnel and facilities.

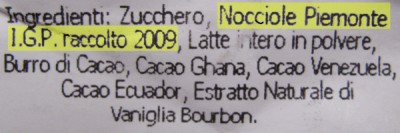

Rule #10: Demand Tonda Gentile delle Langhe. Tonda Gentile delle Langhe is the traditional hazelnut cultivar for gianduia and remains the best choice for flavor and aroma. The use of TGL among recognized masters of gianduia is so invariable that it serves as a useful litmus test for ingredient lists—in part because of the inherent quality of the nuts, but also as a demonstration of the maker’s general commitment to excellence. If a maker uses TGL exclusively, the ingredient list will reflect it. If you just see the generic term “hazelnuts” (nocciole), you’re stepping down the quality ladder.

Rule #10: Demand Tonda Gentile delle Langhe. Tonda Gentile delle Langhe is the traditional hazelnut cultivar for gianduia and remains the best choice for flavor and aroma. The use of TGL among recognized masters of gianduia is so invariable that it serves as a useful litmus test for ingredient lists—in part because of the inherent quality of the nuts, but also as a demonstration of the maker’s general commitment to excellence. If a maker uses TGL exclusively, the ingredient list will reflect it. If you just see the generic term “hazelnuts” (nocciole), you’re stepping down the quality ladder.

TGL sometimes appears on ingredient lists under the cultivar name (e.g., “nocciole varietà Tonda Gentile delle Langhe“). More commonly, you’ll find references to the European Union “protected geographical indication” for TGL hazelnuts grown in the traditional territory: Nocciola Piemonte I.G.P. or Nocciola del Piemonte I.G.P. Be aware that, while all “Piedmont Hazelnuts P.G.I.” are of the variety Tonda Gentile delle Langhe, not all Tonda Gentile delle Langhe hazelnuts are grown in the traditional territory, following the required discipline. The Protected Geographical Indication offers stronger protections against fraud and also assures the consumer that he’s supporting growers in Piedmont (12).

Tonda Gentile delle Langhe kernels.

With respect to nomenclature, consumers should also be aware that, in late 2009, Piedmont’s hazelnut industry consortia renamed TGL as “Tonda Gentile Trilobata”—round, mild, and trilobed (or trefoil), referring to the three-lobed kernel shape—in an effort to better distinguish and protect the product of Piedmont growers. The name change created some controversy, given the long history and clear geographical association of the name Tonda Gentile delle Langhe. For now, only the consortia and some growers appear to be using the new name. Chocolate makers, chocolatiers, chefs, grocers, and consumers throughout Piedmont have been sticking with the older, more elegant name.

Notes:

1. Many of these rules relate to ingredient lists. If an online or mail-order retailer does not include a product’s ingredient list on its web site, ask for it. If they won’t provide it on request, find a retailer who will.

2. Some may prize this balance more than the higher hazelnut content of hand-cut gianduiotti, which can be quite sweet.

3. While there are some good molded gianduiotti in Piedmont, a traveler who eschews molded altogether and seeks out extruded and hand-cut gianduiotti will spare himself a great many middling experiences.

4. Those working with liquor have no involvement in harvest, fermentation, drying, sorting, roasting, winnowing, and initial grinding. Those working with couverture begin with finished chocolate, having even less control over the quality and characteristics of the chocolate.

5. CODEX STAN 87-1981, Rev. 1 – 2003, §2.1.7.2. Gianduia is not currently defined in US regulations.

6. From 1929, items in the trade magazine Il Dolce show a growing interest, among Italian chocolate makers, in the use of lecithin. Its use became common in Italy by the mid-1930s.

7. Though “purity” was an ideal in the Italian chocolate industry from the late nineteenth century, Turinese makers were no more immune to the commercial lure of adulterants than were chocolate makers in other countries. Caffarel Prochet & Co. had an enforcement action brought against it for the use of adulterants—specifically, alabaster powder—in the early 1880s. In correspondence with his brother Matteo, Michele Prochet states that the use of adulterants was practiced by “everybody, more or less.” When similar charges were brought against Talmone in the 1890s—in their case, for using potato starch and fat other than cocoa butter—the industry rallied behind the brothers. In a filing by Caffarel Prochet & Co., Gay Revel & Co., Beata & Perrone, and Moriondo & Gariglio, the chocolate makers stated that, given the market conditions for sugar and cacao, it was impossible to make chocolate consisting solely of cacao and sugar for under 3.20 lira per kilogram. Given the economic challenges Turinese makers faced well into the twentieth century, it is likely that gianduia today is as pure as it has ever been. Bächstädt-Malan, Christian. Per Una Storia dell’Industria Dolciaria Torinese: il Caso Caffarel. Doctoral thesis (Economics and Business), Universitá degli Studi di Torino. 2002. Pp. 88-9. Gianolio, Bartolomeo and Enrico Cavaglià. Memoriale a Difesa nell’Interesse dei Signori Talmone (Enrico, Amedeo, Alberto, Gustavo e Michele), Appellanti da Sentenza 27 Giugno 1894 del Tribunale Penale di Torino. Tipografia Baravalle e Falconieri. Turin. 1895. Pp. 1, 5-6.

8. Spagnoli, Mario. Fabbricazione del Cioccolato. Ulrico Hoepli. Milan. 1926. Pp. 111-5.

9. That’s not to say that hazelnuts are the only nut combined with chocolate in Piedmont. However, when almonds or chestnuts are combined with chocolate, the product is never referred to as gianduia.

10. One could argue that this hinges on when the company began including almonds. If at any time prior to the First World War, Caffarel should be given latitude simply for antiquity’s sake. If the inclusion of almonds began as a response to supply disruptions during the First World War or during austerity and autarky through the Second World War, their use would be a legitimate deviation grounded in history. If, however, the use is more modern, motivated simply by cost calculations before or after the company was acquired by the Swiss company Lindt & Sprüngli, Caffarel deserves no special consideration (even though the company has, by dint of its name and history, sometimes received such consideration).

11. One notable exception is when buying hand-cut, hand-wrapped gianduiotti in Turin. Because each batch is different and because the makers do not sell outside their own shops, they generally do not include an ingredient list at all.

12. TGL grown outside of Piedmont have generally displayed all of the desirable kernel qualities—size, roundness, ease of pellicle removal, and excellent taste and aroma—as those grown in Piedmont. So far, growers have been unable to overcome the productivity and susceptibility challenges the cultivar has shown outside of its native territory. Until they do, it is usually safe to assume that TGL (with or without an I.G.P. designation) are grown in Piedmont.