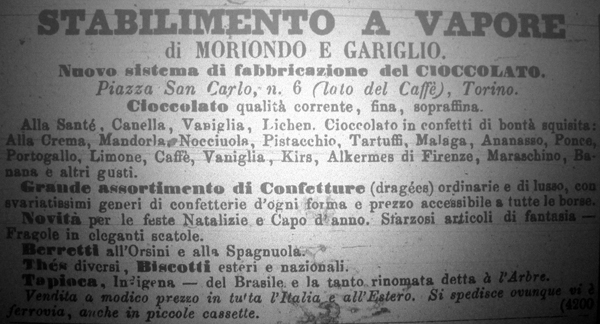

Understanding the nature of the cacao solids used in early gianduia requires a brief examination of the state of the art in Turin during the 1860s.

Understanding the nature of the cacao solids used in early gianduia requires a brief examination of the state of the art in Turin during the 1860s.

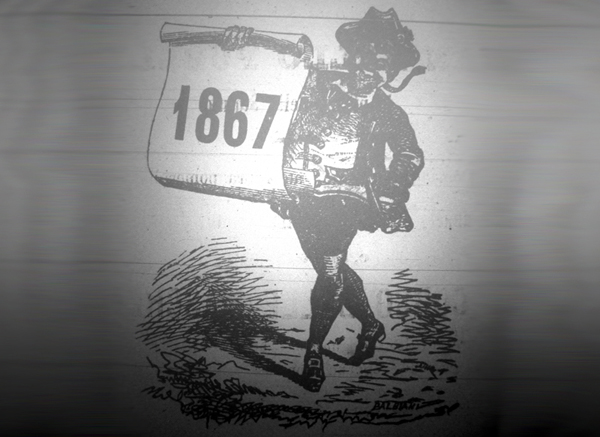

Most efforts to historically contextualize gianduia focus solely on the era of its presumed invention in the mid-1860s. However, as we’ve seen, many components of the gianduia myth first arose in the 1930s, through Cagliano’s article in Il Dolce (1932), Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co.’s “Gianduia 1865” marketing campaign (1936), and the booklet Il Cioccolato ed il Suo Valore Alimentare (1933). The 1930s witnessed a confluence of factors favorable to increased prominence and production of gianduia—a perfect storm, with Benito Mussolini at the eye.

We now jump forward to the 1930s. It was in this decade, between two World Wars, that the myth of gianduia was defined. Though a number of historical factors converged to elevate gianduia in this period (some of which will be discussed in Part 17), two of the key players were Walter Bächstädt and Paolo Audiberti (1).

The Napoleonic myth does not hold water (Part 4). The thirteen-year-old Michele Prochet did not invent gianduia in 1852 (Part 9). The best evidence for Prochet, Gay & Co.’s invention in 1865 is an unsubstantiated statement by Prochet’s company over thirty years after the fact, which openly acknowledges that the claim was contested (Part 13). The tales of gianduia’s naming first appeared over sixty years after the fact and are riddled with internal and external inconsistencies (Part 14). So where does that leave us?

The story of gianduia’s naming is as common as that of its creation. As with the prevailing account of its 1865 origin, the naming myths are also traceable to Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co.