Understanding the nature of the cacao solids used in early gianduia requires a brief examination of the state of the art in Turin during the 1860s.

Understanding the nature of the cacao solids used in early gianduia requires a brief examination of the state of the art in Turin during the 1860s.

We now jump forward to the 1930s. It was in this decade, between two World Wars, that the myth of gianduia was defined. Though a number of historical factors converged to elevate gianduia in this period (some of which will be discussed in Part 17), two of the key players were Walter Bächstädt and Paolo Audiberti (1).

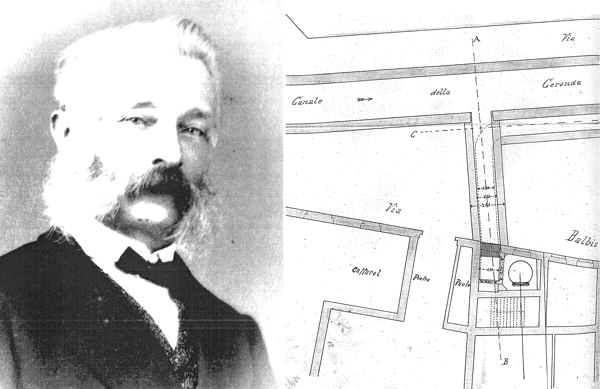

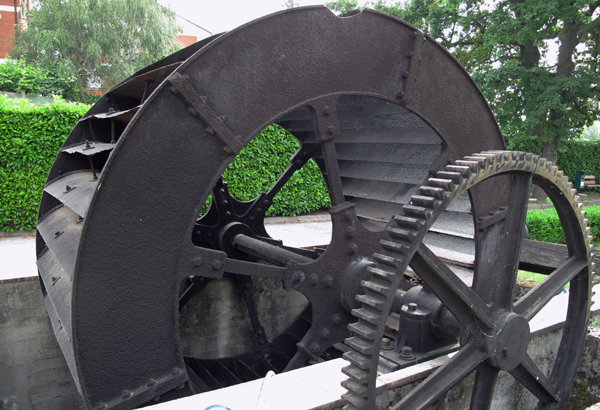

Following the 1837 death of the Bleniese inventor Giovanni Martino Bianchini, Paul Caffarel (pictured above) continued to manufacture chocolate using the same machine Bianchini had installed in the Watzenborns’ converted tannery. He was to be the first of a wave of Waldensian chocolate makers in Turin. Because of the Waldenses’ importance in the rise of gianduia, we will briefly introduce some of the key individuals and companies that will figure into the story ahead.

In the early decades of the nineteenth century, before the Waldenses could safely descend from their valleys, chocolate production in Turin was dominated by immigrants from Canton Ticino in Italian Switzerland—particularly from alpine villages in the Blenio valley. For over a century, harsh winters in the Alps, coupled with a predominately agricultural economy, encouraged seasonal migration for work at lower elevations, including in the population centers of northern Italy (1). Bleniese migrants often took work in the cities as peddlers, chestnut roasters, and, most importantly, cacao grinders.