Most efforts to historically contextualize gianduia focus solely on the era of its presumed invention in the mid-1860s. However, as we’ve seen, many components of the gianduia myth first arose in the 1930s, through Cagliano’s article in Il Dolce (1932), Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co.’s “Gianduia 1865” marketing campaign (1936), and the booklet Il Cioccolato ed il Suo Valore Alimentare (1933). The 1930s witnessed a confluence of factors favorable to increased prominence and production of gianduia—a perfect storm, with Benito Mussolini at the eye.

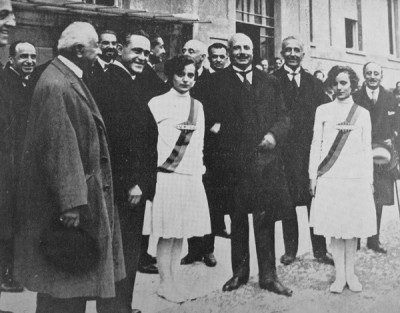

Giuseppe Belluzzo visits UNICA. (Il Dolce, Nov. 1927.)

As early as 1927, Mussolini’s regime began paying greater attention to Turin’s confectionery industry. Towards the middle of the year, the National Fascist Federation of Confectionery Industry was created under the umbrella of the National Fascist Confederation of Industry (1). In October, Giuseppe Belluzzo, Minister of National Economy, visited the Turin factory of UNICA, the confectionery conglomerate that included the former Talmone and Moriondo & Gariglio, among others (2).

In March of 1928, the confectionery trade publication Il Dolce became an official arm of the National Fascist Federation of Confectionery Industry (3). Over the remaining years of publication (through 1935), the magazine increasingly reflected Fascist ideological concerns and propaganda objectives (4). In 1932, Mussolini personally visited UNICA’s factory, drawing admiring crowds and a fawning report in Il Dolce (5). This was the same year that Cagliano published his account of gianduia’s origins in the magazine (6). One year later, the National Fascist Federation of Confectionery Industry published Il Cioccolato ed il Suo Valore Alimentare (7).

The basic story of gianduia appealed to the sense of intense nationalism associated with Italian Fascism. Gianduia was connected to Turin, Italy’s first capital and the philosophical epicenter of the Risorgimento. It bore the name of a powerful symbol of independence and national unification. And, with Italy’s continuing lag in industrialization, the government prized the growth and success of Turin’s confectionery industry (8).

Mussolini visits UNICA. (Il Dolce, No. 81, November 1932.)

Beyond their accounts of gianduia’s origins, both Cagliano and the anonymous author of Il Cioccolato ed il Suo Valore Alimentare appeal to nationalism in various ways (9). Both praise the excellence of Italian chocolate, claiming that it was at times internationally recognized as among the best in the world (10). Both make exaggerated claims about Italian mechanical innovation and modernization in chocolate-making (11). To prove the derivation of the Swiss chocolate industry from the Italian, both advance the false myth about Cailler learning his craft from Caffarel in 1815 (12). In both works, gianduia stands as one of a series of grand chocolate-related achievements of the Italian nation.

Throughout the 1930s, Fascist nationalism often found expression in the identification and celebration of local and regional foods. Propaganda campaigns “reinforced the notion that Italian cuisine was national patrimony worth defending” (13). The regime organized festivals to promote domestic breads, rice, grapes, and wine (14). This nationalistic streak sparked a surge of interest in, and writings about, the origins and history of distinctively Italian foods (15).

The Fascist-era creation of gianduia myths fit neatly with such propaganda objectives. In August of 1929, the National Fascist Federation of Confectionery Industry announced its collaboration with the Touring Club Italiano in providing material for the first Guida Gastronomica Italiana, observing that “all initiatives that bring honor to our Fatherland merit our most unconditional consent” (16). The Federation submitted a list of regional specialties, including gianduiotti, whose origins were described in terms drawn directly from Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co.’s re-printed 1899 statement (17). When the Guida Gastronomica finally went to press, gianduiotti received a brief mention as evidence of Turin’s “glorious tradition” in confectionery art (18). Continuing the emphasis on local and regional confectionery specialties, the National Fascist Federation of Confectionery Industry republished its fuller, more detailed list two years later (19).

Of itself, pride—even disproportionate pride—in distinctively Italian foods might have been a relatively harmless expression of nationalism. In reality, this boosterism worked in tandem with Fascist policies in furtherance of autarky—of economic (and alimentary) self-sufficiency. Even before the March on Rome, Fascist squads walked the streets to ensure that retailers were selling only Italian-produced goods (20). Through the 1930s, the Fascists worked to replace budding post-war consumerism with an ethic of consumption that prioritized the economic health of the nation over individuals’ wants and, in time, even over their nutritional needs (21). Mussolini’s government employed moral suasion, propaganda, state-sponsored science, regulatory coercion, and trade policy to move towards autarky.

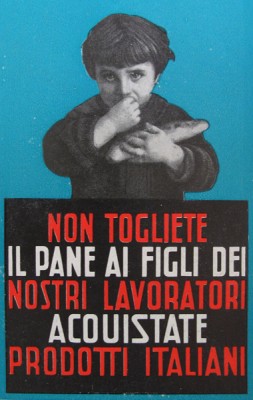

Il Dolce, No. 69, November 1931.

The confectionery industry was not immune from the regime’s efforts. In June of 1931, the National Fascist Federation of Confectionery Industry reprinted a circular from Minister Belluzzo, proclaiming that it was the moral duty of every Italian to prefer Italian products over comparable foreign products. In case moral duty proved insufficient, penalties were provided for noncompliant businesses (22). Later that year, as Fascist propaganda began replacing advertising on the covers of Il Dolce, this message was reinforced with the image of somber child holding a loaf of bread, over the caption: “Don’t Take Bread from the Children of Our Workers. Buy Italian Products” (23).

Despite official encouragement to “buy Italian,” the gradual shift towards autarky—and its bedfellow, austerity—proved devastating to Italian confectionery. Cost and availability of cacao had always been a problem for Turin’s chocolate makers, but Mussolini’s policies exacerbated the situation. Tariffs, import quotas, and the 1936 devaluation of the lira were damaging (24). Trade sanctions by the League of Nations following the invasion of Ethiopia (1935) and the alignment with Hitler’s Germany in the Pact of Steel and Tripartite Pact (1939-40) further isolated Italy, pushing the country closer to Mussolini’s autarkical ideal. The cacao crisis deepened. Cost and availability of sugar became problematic. In the thriving black market, towards the end of the war, chocolate sold for five times the official price and sugar nearly ten times (25). Export markets dried up. Resources flowed from Italy to Germany. Domestic consumers spent ever greater percentages of their income for basic foods, with little to spare for luxuries like chocolate or caramels. Turinese confectioners found themselves in a desperate struggle just to survive (26).

The Italian-German Alliance, Before and After (Il Cesare di Cartapesta: Mussolini nella Caricatura. GEC, 1945.)

In this economic setting, Italians turned to substitutes for ingredients whose cost or rarity put them out of ready reach (27). Gianduia became even more attractive to producers because—apart from its nationalistic associations and Italianità—the use of Piedmont hazelnuts reduced the need for cacao. Unlike prior periods for which the “necessity” meme has been invoked (e.g., the 1860s or during the Continental System), confectioners’ severe challenges in obtaining cacao and sugar during the Fascist era are well documented by contemporary sources (28). The most vivid illustration of the importance of gianduia to producers appears in the minutes of a special meeting of the board of Caffarel Prochet & Co. on April 16, 1942. In explaining the “less than rosy” sales projections for the year, the board notes that, “as of December 31, 1941, the use of almonds and hazelnuts in the products we manufacture has been forbidden, and we are unable to obtain the best material available for partial replacement of cacao” (29).

Mussolini chocolate molds (Caffarel, 170 Anni; 1996).

By prohibiting the heavy use of hazelnuts by Turinese chocolate makers, the government intended to make the non-animal protein and fat from the nuts available for laborers and soldiers, rather than as a luxury for the upper class (30). The increased demand for hazelnuts during the Fascist era—both as an ingredient for chocolate makers and as a nutritionally dense food for workers—led to the first serious efforts at cultivation of hazelnuts as a cash crop in Piedmont (31). Increased hazelnut output favored gianduia production during the Mussolini years and put hazelnut cultivation in Piedmont on the road to steady expansion through the remainder of the twentieth century.

Through the 1930s and early 1940s, Fascist economic policy and ideology drove production of, and storytelling about, gianduia. Gianduia would only grow in popularity and affordability during the post-war recovery, particularly during the years of the “economic miracle.” With greater abundance of hazelnuts and better economic times, manufacturers had no economic motive to deemphasize gianduia. A fair argument can be made that, second only to gianduia’s inventor, Benito Mussolini is the most important historical figure in the rise of Turin’s signature confection.

Notes:

1. Il Dolce, No. 23, January 1928. Pp. 19-22. This was during the early period of Fascist syndicalism, prior to the turn to corporatism in the 1934 reforms. See Welk, William. Fascist Economic Policy: An Analysis of Italy’s Economic Experiment. Russell & Russell. New York. 1938. Pp. 55-8.

2. Il Dolce, No. 21, November 1927. Pp. 221-4. UNICA was an acronym for Unione Nazionale Industria Cioccolato ed Affini.

3. Il Dolce, No. 25, March 1928. P. 2 (masthead).

4. As the most obvious sign of this turn, in late 1931 propaganda pieces began appearing on the magazine’s front cover, which had formerly been occupied by paid full-page advertisements.

5. Il Dolce, No. 81, November 1932. Pp. 349-52.

6. Cagliano, A. “Frammenti di Storia del Cacao e del Cioccolato con Particolari Cenni all’Italia e Torino.” Il Dolce: Rivista delle Industrie Italiane del Cioccolato, Biscotti, Caramelle, Confetture ed Affini. Year 7, No. 72, February 1932. Pp. 48-53.

7. “Il Cioccolato ed il Suo Valore Alimentare,” Rivista Semestrale di Studi Economici e Tecnici, Anno 1, n. 3. Edited by the Federazione Nazionale Fascista dell’Industria Dolciaria. Turin. November, 1933.

8. Mussolini’s embrace of Turin’s confectionery industry demonstrated some opportunistic flexibility, given his government’s general disdain for culinary indulgence. See Helstosky, Carol. “Fascist Food Politics: Mussolini’s Policy of Alimentary Sovereignty.” Journal of Modern Italian Studies. 9(1) 2004. P. 10.

9. With many similarities between the works, it seems possible that Il Cioccolato ed il Suo Valore Alimentare was written or edited by Cagliano.

10. Cagliano, 53. Il Cioccolato, 20.

11. “Exaggerated” is too soft a word. Cagliano falsely claims that Italy was the first nation to mechanically produce chocolate (51). Il Cioccolato falsely claims that Italy was among the foremost European countries for the modernity of its factories, capitalization, and technical ability (20-1). Not only did Italy lag in the early 1930s, but the gap would only grow as Mussolini’s autarkical objectives were more fully realized.

12. Cagliano, 52. Il Cioccolato, 25.

13. Helstosky [JMIS], 9-10.

14. Helstosky [JMIS], 6.

15. Helstosky, Carol. Garlic & Oil: Food and Politics in Italy. Berg. Oxford. 2004. P. 103.

16. Il Dolce, No. 42, August 1929. P. 196.

17. “Gianduiotti were created in 1865 by the former firm Prochet Gay & Co. and were given the name of givo (which in Piedmontese dialect means May bug). It was in 1867, at the time of the Fantastic Fair of Turin that this nickname was changed to that of Gianduia, as homage to the traditional Piedmontese mask.” Il Dolce, No. 42, August 1929. P. 197.

18. Touring Club Italiano (ed. Arturo Marescalchi). Guida Gastronomica d’Italia. Mondaini & Co. Milan. 1931. P. 22.

19. Il Dolce, July 1933. P. 210.

20. Helstosky [G&O], 59.

21. Helstosky [G&O], 66.

22. Il Dolce, No. 64, June 1931. Pp. 189-90.

23. Il Dolce, No. 69, November 1931. P. 1.

24. Bächstädt-Malan, Christian. Per Una Storia dell’Industria Dolciaria Torinese: il Caso Caffarel. Doctoral thesis (Economics and Business), Universitá degli Studi di Torino. 2002. Pp. 105-6.

25. Helstosky [G&O], 111-2. Though some of the same isolating forces were at work during the First World War, the effect was less harmful to Italian chocolate makers (Spagnoli, Mario. Fabbricazione del Cioccolato. Ulrico Hoepli. Milan. 1926. P. 113.).

26. Bächstädt-Malan, 108-18. To say they struggled to survive is no mere figure of speech. Many confectionery workers and managers (including Walter Bächstädt) were drafted and put in harm’s way during the war. Also, as the industrial capital of Italy, Turin was subjected to heavy, repeated bombing by the British and American air forces through the early 1940s that destroyed buildings and left large swaths of the city without electricity and water. Caffarel Prochet & Co.’s factory was one of many destroyed in the air raids.

27. Helstosky remarks that, in wartime cookbooks, “the names of the various dishes suggest that Italian women went from ‘cooking with little’ to ‘cooking with nothing’: torta autarchica; polpettine di finta carne (meatballs made with pretend meat); and polpettine fatte di nulla (meatballs made of nothing)” (Helstosky [G&O], 109). The Padovanis reprint a 1940 recipe by a San Giorgio Canavese confectioner for cioccolato autarchico, made with one kilo of darkly roasted almonds, two kilos of sugar, one kilo of hydrogenated vegetable oil, half a kilo of powdered milk, and vanilla—no cacao solids whatsoever. Padovani, Clara Vada and Gigi Padovani. Gianduiotto Mania — La Via Italiana al Cioccolato: Storia, Fortuna, Ricette. Giunti, 2007. Pp. 34.

28. Though the difficulty is already detectable in the early 1930s (e.g., in Il Dolce), the depth of the problem becomes more apparent in the minutes of special meetings of Caffarel Prochet & Co. during the war years (Bächstädt-Malan, 107-15). Oddly, the necessity meme so common in accounts of gianduia’s origins does not appear before or even during the Fascist era. It could be that subsequent twentieth century writers’ attribution of “necessity” as the instigation for gianduia’s invention represents a lingering outlook forged by living through autarky and austerity in Mussolini’s Italy.

29. Bächstädt-Malan, 109. Perhaps as a legacy of its trial by fire in this time of war, autarky, and austerity, Caffarel is the only Piedmontese maker of note to use almonds (albeit in a very small proportion), in addition to the traditional hazelnuts, for their gianduia.

30. Early in the Ethiopian invasion, Carlo Foà, in recommendations to the Provincial Fascist Federation of Milan, urged increases in production of vegetable sources of protein, such as peanuts, sesame, and soy, as well as efforts to reduce upper class fat and protein consumption to better provide for the nutritional needs of laborers (Helstosky [JMIS], 11-2).

31. Dardanello, Ferruccio. “IGP Nocciola Piemonte: Relazione Storico – Tecnico – Economica.” Camera di Commercio Industria Artigianato e Agricoltura di Cuneo, Allegato n. 7. December 20, 1993. (In support of PGI application, Dossier No.: IT/PGI/0117/0305.) P. 3.