In Noka Part 7, we employed process of elimination in an attempt to identify Noka’s couverture source. Onward…

When I began preparing a spreadsheet of single-origin chocolates months ago, I never would have guessed that the process of elimination would be so effective in determining Noka’s chocolate supplier. At best, I hoped it would narrow the field somewhat, with the remaining candidates for each origin blind taste-tested against Noka’s chocolate to nail down the sources. When I was unable to find any maker other than Bonnat whose chocolate fit the bill for any of the four origins, that rendered taste-testing superfluous.

But I did it anyway. Tasting would be the only way to confirm the results of the more analytic process described in Noka Part 7. Also, though I had every reason to believe Noka was using Bonnat for its Venezuelan single-origin, tasting would be the only way of telling which of Bonnat’s three Venezuelan chocolates Noka was using. Though this would require chiseling my way through pounds of premium single-origin chocolate from the world’s best makers, it was a sacrifice I was prepared to make.

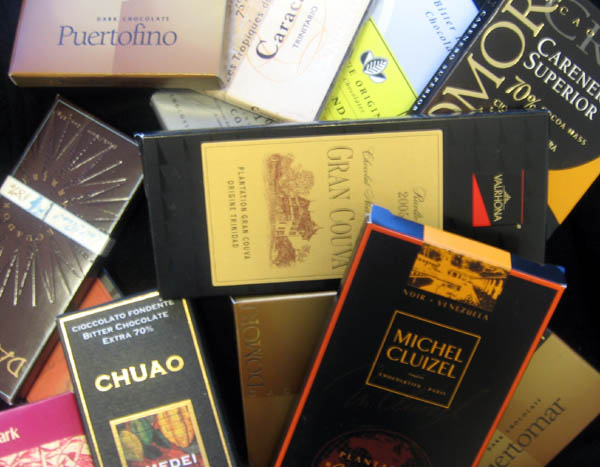

The taste-testing was not meant to be exhaustive. The idea was merely to see if there was an identifiable similarity between a given Noka variety and any blindly sampled single-origin chocolates from the same origin (broken up to conceal distinctive molding patterns). Each slate of single-origins was tasted alongside Noka’s chocolate multiple times.

Ivory Coast. With only two possibilities—Bonnat and Theo—this was the slimmest of the comparisons. Bonnat was the clear match for Noka’s “Bambarra.” The Theo chocolate, despite a slightly lower percentage of cacao solids, had a much bolder taste and greater bitterness and astringency. Texturally, the Noka and Bonnat both seemed to have high cocoa butter content, leaving an unusually fatty mouthfeel. (The only chocolate sampled that felt fattier was Hachez’s Arriba.) Judging from flavor alone (i.e., without thinking about child slaves), Bonnat’s chocolate tasted better than Theo’s. However, of the four Noka varieties, this one was predictably the weakest.

Trinidad. I assembled four chocolates to compare with Noka’s “Tamborina”: Bonnat (Trinité), Pralus (Trinidad), Amedei (Trinidad), and Valrhona (Gran Couva 2005). This tasting nicely demonstrates the relative insignificance of terroir as a factor in chocolate flavor. Despite the fact that all four chocolates were made from the same variety of bean (i.e., Trinitario) on an island smaller than Delaware, they taste dramatically different.

The Valrhona was noticeably sweeter than the others (which is to be expected, given its lower cacao percentage of 64%), lightly acidic, slightly nutty, and thin-tasting. Pralus was surprisingly mild for a 75%, with a fairly dark roast (but little bitterness) and gentle fruity flavor—easily the mellowest of this bunch. Amedei was fragrant and fruity, with just a touch of acidity, no bitterness, and long finish. Bonnat had a very dark roasted flavor (“smoky,” as one taster described it), verging on bitterness, but counterbalanced with strong, distinctive acidity (also detectable in the sharp fragrance).

Bonnat was a solid match for Noka’s “Tamborina.” Both were distinctive in their fragrance, acidity, and more rustic texture. How did the Bonnat stack up against the other Trinidads? Middle of the pack—ahead of Valrhona by a length, neck and neck with Pralus, with Amedei in the distance wearing flowers and having its picture taken with pretty girls.

Ecuador. I wasn’t able to get my hands on every Ecuadorian single-origin made. I had to settle for eight, though only one premium maker was left out of that assembly (i.e., Pierre Marcolini’s 72%). The line-up for comparison with Noka’s “Carmeñago” consisted of: Bonnat (Equateur), Pralus (Equateur), Plantations (Arriba), Domori (Arriba), Amedei (Ecuador), Dagoba (Los Rios), Chocovic (Guaranda), and Hachez (Arriba).

Though not as enjoyable, overall, as the Trinidadian and Venezuelan chocolates, this was an interesting and diverse bunch. The Pralus had very smooth texture and a mellow, rounded chocolate flavor, with just a little nuttiness. The Domori was comparatively untamed, with strong aroma, bracing astringency, and an edgily robust flavor. Amedei had a silky texture, almost no bitterness, more red fruitiness than any of the other Ecuadorian chocolates, a mild hint of coconut, and super-long finish. Dagoba came up a little short in the texture department (due to some grittiness), had more astringency than most, and so-so flavor and finish. Bonnat had a very typical Arriba flavor (in a good way), was darkly roasted and bitter (but not overly so), and had mild astringency. Chocovic had a light, sugary aroma, smooth texture, and a mellow chocolaty flavor with strong coconut notes. The Plantations 65% was smooth in texture, but rough around the edges in flavor, with big aroma and a bold and slightly bitter taste. Hachez had a very fatty mouthfeel from added cocoa butter, perhaps intended to cloak the strong bitterness and astringency of the underlying chocolate.

Bonnat was an easy match for Noka’s “Carmeñago,” with both having a very classic Arriba flavor, similar level of roast and astringency, and comparable texture and mouthfeel. Nothing else even came close.

Noka’s use of Bonnat for Ecuador seems like a pretty good choice. Though it wasn’t the best of the bunch, it did make a good showing. My notes show the following ranking (from highest to lowest): Amedei, Pralus, Bonnat, Chocovic, Domori, Vintage Plantations, Dagoba, and Hachez. (I’m not at all dogmatic about these rankings, by the way. Tastes vary in chocolate. Once you get beyond the most common flaws in beans and processing, chocolate lovers are going to disagree. With the exception of the Hachez, which was really out of its league, these chocolates were all good to great.)

Venezuela. I assembled a baker’s dozen of Venezuelan chocolates: Amedei (Venezuela and Chuao), Chocovic (Ocumare), Valrhona (Palmira 2005), Cluizel (Hacienda Concepcion), Bonnat (Chuao, Hacienda El Rosario, and Puerto Cabello), Pralus (Venezuela), and Domori (Carenero Superior, Puertomar, Puertofino, and Porcelana). Despite the number of chocolates in the field, finding a match for Noka’s distinctive “Vivienté” was little challenge.

Both of the Amedei chocolates were excellent—rounded and rich, with fruity notes, smooth texture, and long finish. Neither had the sharpness, lively acidity, and sour undercurrents of the Venezuelan chocolate Noka uses. The Chocovic, with its nutty, sugary aroma, almost no bitterness, and caramel-like sweetness, also failed to match the Noka. Valrhona’s plantation bar hinted at “Vivienté” with some acidity in the aroma, but ultimately proved to be a much milder, sweeter chocolate. Cluizel’s plantation bar was mellow, slightly sweet, and not very complex—nowhere near the character of Noka’s chocolate. The Pralus was a pleasant middle-of-the-road chocolate—like a good hot chocolate, having a nice rounded cocoa flavor, a fairly dark roast, just a touch of bitterness, and a smooth, lingering finish. Nothing like “Vivienté.”

All of the Domori chocolates were outstanding. The Carenero Superior was the roughest of the four, with a more forward bitterness, but strong aroma, and smooth texture. Puertofino was the most distinctive of the Domori lot, with a sharp aroma, prominent (but well-controlled) acid and sour elements, flawless texture, and great finish. Puertomar and Porcelana both had quintessential chocolate flavors, terrific aroma and intensity, wonderful balance, and perfect mouthfeel. Domori’s Venezeualan chocolates (particularly those in the Château line) are as good as chocolate gets. However, none had the same distinctive qualities as Noka’s “Vivienté.”

Lastly, Bonnat’s trio of Venezuelan chocolates. Bonnat’s Chuao was much weaker than Amedei’s definitive version from the same coastal valley. With a faint aroma, shortage of character, more pronounced bitterness, and a rather dark roasted flavor, it was also marred by a slightly chalky texture. A good chocolate, but no match for the thoroughbreds in this tasting. Hacienda El Rosario, from Maracaibo, had similar characteristics in roast and texture (though not quite as chalky as the Chuao), but a more rounded flavor, light acidity, and a subtle spiciness.

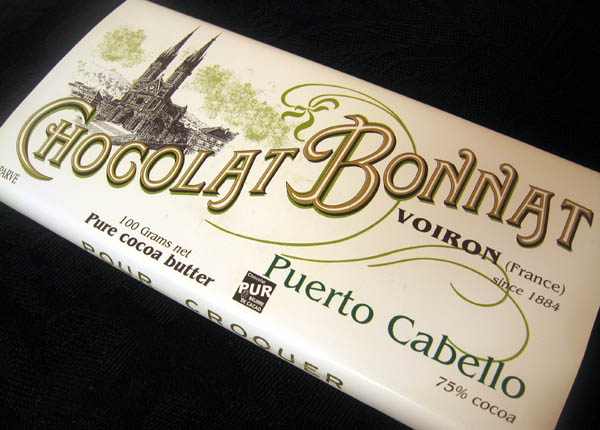

Then there was Puerto Cabello. The sharp, acidic aroma alone suggested I’d found the match for Noka’s “Vivienté.” Tasting it sealed the deal. Like the Venezuelan couverture Noka uses, Bonnat’s Puerto Cabello had a very distinctive flavor, with strong acidity, dark roast, slight astringency, a lingering sourness, and the more rustic texture common to Bonnat’s chocolates. If Noka’s “Vivienté” isn’t Bonnat’s Puerto Cabello, I’ll eat my hat (and post photos and detailed tasting notes).

Ranking the Venezuelan chocolates is tough, because so many of them are exceptional. But, if I had to do it, it would go as follows (from highest to lowest): Domori (Puertomar), Domori (Porcelana), Amedei (Venezuela), Domori (Puertofino), Amedei (Chuao), Pralus (Venezuela), Bonnat (Puerto Cabello), Domori (Carenero Superior), Bonnat (Hacienda El Rosario), Cluizel (Hacienda Concepcion), Valrhona (Palmira 2005), Chocovic (Ocumare), and Bonnat (Chuao).

The blind tasting consistently confirmed what was already clear from the process of elimination analysis. Noka is using Bonnat’s chocolates.

Katrina Merrem’s statement to me (in Part 6) that Noka’s couverture supplier is making its chocolate to her specifications appears to be a lie. Bonnat has been making single-origin chocolates from Venezuela, Ecuador, Ivory Coast, and Trinidad with 75% cacao solids (including additional cocoa butter), no vanilla, and no soy lecithin for many years–long before Noka came onto the scene.