Though gianduia is now available year-round, it was originally a seasonal product, available during late autumn and winter months.

Some have attributed gianduia’s original seasonality to the liturgical calendar—Advent, Christmastide, Epiphany, and Carnival. That may have been a factor, in some measure, given the constant struggle of nineteenth century Italians to obtain basic foods and the culinary extravagance reserved for holidays (1). Though gianduia’s association with Carnival, in particular, was both early and deep, it was but a secondary contributor to the confection’s limited availability.

Gianduiotti by Silvio Bessone (Vicoforte).

Chocolate makers fashioned gianduiotti in winter months primarily because that’s when hazelnuts were available. Tonda Gentile delle Langhe nuts in Piedmont generally reach maturity in the last week of August (2). The harvest, sun-drying to reduce water content, shelling, and transportation to market account for gianduia’s traditional appearance in October (3).

Torrone by D. Barbero (Asti).

The disappearance of gianduia in March arose from several factors. First, the high oil content of hazelnuts makes them perishable, susceptible to rancidity from oxidation and microbes, particularly when shelled, roasted, blanched, and ground (4). Storing the nuts unshelled, even in the absence of commercial refrigeration, could allow them to be used as late as the next harvest (albeit with some deterioration). However, the seasonal flexibility of Piedmontese food culture offered little motivation to hold hazelnuts for out-of-season use.

Nocciolini de Chivasso by Bonfante (dime for scale).

Second, the supply of hazelnuts was limited. As previously discussed, at the time of gianduia’s emergence hazelnuts were not cultivated as a cash crop (5). Also, the Piedmontese had incorporated hazelnuts in their cuisine and confectionery long before the Waldenses developed gianduia (6). Manifold, established uses for hazelnuts in winter cookery quickly depleted the seasonal supply of hazelnuts.

Gianduiotti by Cioccolato Puro (Pinerolo).

The third reason for the disappearance of gianduiotti in March relates to their composition. While the fat from cacao liquor (i.e., cocoa butter) melts at a little below body temperature, the fat from hazelnuts—and hazelnuts are mostly fat—is liquid at room temperature. The combination produces a soft, temperature-sensitive paste that’s much easier to work with, store, and distribute in cold weather (7).

The softness and temperature-sensitivity of gianduia led to another of the confection’s defining features. To prevent them from sticking together and from melting in the hand before consumption, gianduiotti were individually-wrapped with silver or gold paper or tin foil (8).

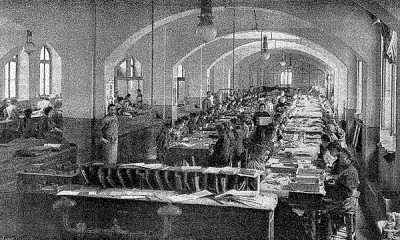

Hand-wrapping at Moriondo & Gariglio, 1898 (Ainardi, 85).

This made gianduiotti among the world’s first commercially produced individually-wrapped candies, decades before Leo Hirschfield’s Tootsie Roll (1896) or Milton Hershey’s Kisses (1907). Wrapping was done by hand, usually by women, well into the twentieth century (9). Caffarel Prochet & Co.’s first machine-wrapped gianduiotti left the factory in 1941 (10).

By the middle of the twentieth century, increased hazelnut production, commercial refrigeration, and the growing importance of gianduiotti in product lines led to the confection’s availability year-round (11).

1. “In the nineteenth century, at least half of the family budget went to purchase the staple food of polenta, bread, or pasta, along with a companatico, usually oil, onions, or other vegetables.” “The only time that Italians ate plentifully was on holidays, when food brought people together.” Helstosky, Carol. Garlic & Oil: Food and Politics in Italy. Berg. Oxford. 2004. Pp. 16, 15, 25. See also, Marsero, Mario. Dolci, Delizie Subalpine: Piccola Storia dell’Arte Dolciaria a Torino e in Piemonte. Lindau. Turin. 1995. Pp. 33-7.

2. This is early, relative to most hazelnut cultivars. Growers value precocity of nut maturation because it increases the odds of harvesting before weather worsens. Farinelli, D., M. Boco, and A. Tombesi. “Ulteriore Valutazione di Genotipi di Nocciolo (C. avellana) Ottenuti Mediante Incrocio tra le cv. Tonda Romana e Tonda di Giffoni.” 2° Convegno Nazionale sul Nocciolo. Giffoni Valle Piana. 2002. P. 160. See also (on precocity), De Salvador, F.R., M. Giorgioni, D. Massari, S. Bizzarri, P. Onorati, and F. Kaswalder. “La Collezione di Vico Matrino (VT) per il Rinnovo Varietale ed il Miglioramento Qualitativo del Nocciolo.” 2° Convegno Nazionale sul Nocciolo. Giffoni Valle Piana. 2002. P. 175.

3. Marsero, Mario. “Gianduia: Storia di un Cioccolato,” Pasticceria Internazionale, n. 141. 2000. P. 141.

4. Allen, J.C., and R.J. Hamilton. Rancidity in Foods. Aspen Publishers. New York. 1999. Pp. 251-2. As late as 1934, Guido Marucco describes hazelnuts as being consumed fresh at the time of harvest and dried through winter and into spring. “Noci e Nocciole nelle Industrie Dolciarie,” in Il Dolce, May 1934. P. 142.

6. Anonymous. Il Confetturiere Piemontese, che Insegna la Maniera di Confettare Frutti in Diverse Maniere. Beltramo. Turin. 1790. Pp. 5, 35, 48, 85, 128, 135, 363, 365, 369. See also, Il Dolce, May 1934. P. 144.

7. Try walking around Turin on a summer afternoon with a bag full of hand-cut gianduiotti. After a couple of hours, you’re likely to find a puddle of hazelnut oil at the bottom of the bag. (The smell of the loose oil will be indescribable, almost justifying the mess.)

8. Marsero [2000], 141. In Italy, as in America, tin foil began to be supplanted by aluminum foil in the 1930s and 1940s.

9. Ainardi, Mauro Silvio and Paolo Brunati. Le Fabbriche da Cioccolata: Nasscita e Sviluppo di un’Industria Lungo i Canali di Torino. Umberto Allemandi & C., 2008. P. 87. Marsero, Mario. Dolci, Delizie Subalpine: Piccola Storia dell’Arte Dolciaria a Torino e in Piemonte. Lindau. Turin. 1995. P. 75.

10. Caffarel S.p.A (ed.). Caffarel, 170 Anni: Avanti, Sempre Più Avanti (La Meravigliosa Storia del “Cioccolato d’Autore”). Caffarel S.p.A. 1996. P. 257

11. This perenniality extends to the menus of many of Piedmont’s best restaurants that are otherwise strictly seasonal. Oddly, many top restaurants in the United States better observe gianduia’s seasonality, cuing off of Oregon’s hazelnut season. (Of course, unlike many restaurants in Piedmont, American restaurants feel no pressure to make gianduia available for tourists in the off-season.)