We now turn to the third necessary component of gianduia: roasted hazelnuts. Before getting into specifics, some general information may be helpful.

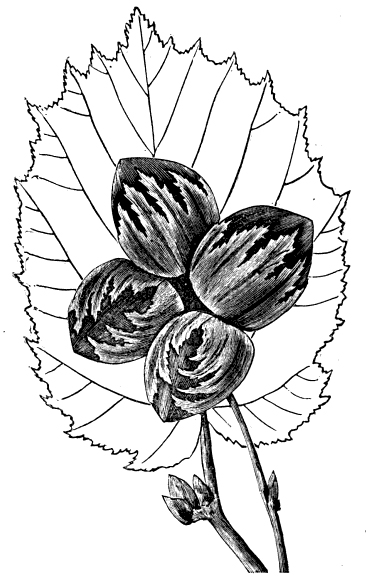

The genus Corylus, or hazels, consists of about fifteen species of deciduous trees and shrubs. Two of these species, the European hazel (C. avellana) and Giant filbert (C. maxima) are commonly cultivated for food use (1). The Giant filbert, more common in the Balkans, Turkey, and Caucasia, produces larger nuts, enclosed in a longer, more constricted husk (or involucure). The two species are fully interfertile, resulting in many hybrids.

The terms “hazelnut,” “filbert,” and “cob” have sometimes been used synonymously and sometimes not. In 1942, the American Joint Committee on Horticultural Nomenclature attempted to standardize American usage by referring to the genus (and nuts) as “filbert” (2). Despite the technical correctness of “filbert” in American English, in 1994 the Oregon Filbert Commission changed its name to the Oregon Hazelnut Commission to reflect the more common usage of “hazelnut” in domestic and international markets (3).

The European hazel and hybrids account for most of the production from the world’s leading producers. Turkey remains the leading source of hazelnuts, accounting for 65% of world production, based on 2007 statistics from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Italy is a distant second with 16% of world production. The United States, in third, accounts for about 4% of world production (almost entirely from Oregon’s Willamette Valley). While third place honors have varied in the nearly fifty years that the FAO has tracked international hazelnut production, in every year Turkey has led the world, followed by Italy.

The European hazel and hybrids account for most of the production from the world’s leading producers. Turkey remains the leading source of hazelnuts, accounting for 65% of world production, based on 2007 statistics from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Italy is a distant second with 16% of world production. The United States, in third, accounts for about 4% of world production (almost entirely from Oregon’s Willamette Valley). While third place honors have varied in the nearly fifty years that the FAO has tracked international hazelnut production, in every year Turkey has led the world, followed by Italy.

In Italy, as in Turkey, hazelnut cultivation and harvesting relies heavily on manual labor. The plants are allowed to follow their natural growth pattern as multiple-stemmed shrubs, limiting mechanization (4). Nuts are shaken from the trees (e.g., by beating the branches with sticks) or allowed to drop at maturity onto the swept ground below. They are collected (often with a vacuum hose), then dried either in the sun or indoors with gentle heating. (In Oregon, the plants are placed in orderly rows and trained or grafted to produce a single trunk and vertical habit, allowing mechanization throughout the growing season, ending with large sweepers and harvesters to collect the nuts after they’ve fallen to the ground.) Harvest time varies somewhat by geography, climate, and cultivar, but is generally in the fall.

Within Italy, the bulk of hazelnut production is in the central and southern regions of Campania, Lazio, and Sicily. Piedmont, in the northwest, is the fourth leading producing region, though only a distant fourth. Piedmont has hazelnuts on less than a third of the area under cultivation in Campania and about half the area under cultivation in Lazio and Sicily. The four regions combined account for over 90% of Italy’s hazelnut production, with Piedmont producing a little over 13%. Within Piedmont, almost all hazelnut production is from the adjoining provinces of Cuneo and Asti (5).

Despite Italy’s tremendous strength in hazelnut production through most of the twentieth century, at the time of gianduia’s invention in the second half of the nineteenth century hazelnuts were not yet cultivated as a cash crop in Piedmont. While wild hazels were abundant in the rocky hills of Monferrato, Roero, and the Langhe, the Piedmontese only casually propagated hazels for subsistence (e.g., trees near farm houses or in vineyards) and ornamental purposes (e.g., running along rural roads) (6). To the extent harvested and foraged nuts were not used by the locals, modest surpluses were sold to confectioners in Turin or even France (7). It was only in the closing years of the nineteenth century that the first dedicated hazelnut-shelling facilities emerged in Alba and Cortemilia (8).

Despite Italy’s tremendous strength in hazelnut production through most of the twentieth century, at the time of gianduia’s invention in the second half of the nineteenth century hazelnuts were not yet cultivated as a cash crop in Piedmont. While wild hazels were abundant in the rocky hills of Monferrato, Roero, and the Langhe, the Piedmontese only casually propagated hazels for subsistence (e.g., trees near farm houses or in vineyards) and ornamental purposes (e.g., running along rural roads) (6). To the extent harvested and foraged nuts were not used by the locals, modest surpluses were sold to confectioners in Turin or even France (7). It was only in the closing years of the nineteenth century that the first dedicated hazelnut-shelling facilities emerged in Alba and Cortemilia (8).

The delayed emergence of industrial processing and focused commercial production of hazelnuts in Piedmont suggests that gianduia was the horse drawing the hazelnut cart in the early decades of the twentieth century (9). This is hard to reconcile with the common narrative about gianduia emerging out of a superabundance of hazelnuts and shortage of cacao. Until production of gianduia created the demand to justify hazelnuts as a cash crop, prior agricultural practices could only have supplied hazelnuts on a very limited, seasonal basis.

Over the course of centuries, the relative isolation provided by the hills of Monferrato, Roero, and the Langhe permitted the gradual development of a unique cultivar of European hazel. That cultivar would come to be known as Tonda Gentile delle Langhe, of which more must be said.

The Langhe.

Notes:

1. Zohary, Daniel and Maria Hopf. Domestication of Plants in the Old World. Third Edition. Oxford University Press. 2002. Pp. 190-1.

2. Rosengarten, Jr., Frederic. The Book of Edible Nuts. Dover Publications. New York. 1984. P. 95.

3. Pace the American Joint Committee on Horticultural Nomenclature, I use the word “hazelnut” in these reports, not only because the Oregonians—with 99% of all US hazelnut production—know of which they speak, but because “hazelnuts” have always sounded more appetizing to me than “filberts.”

4. Me, G., C. Radicati, and C. Salaris. “Rejuvenation Pruning of Hazelnut cv. Tonda Gentile delle Langhe,” Proceedings of the III International Congress on Hazelnut. Acta Horticulturae: 351. 1992. P. 439.

5. Cristofori, Valerio. Fattori di Qualità della Nocciola. Tesi di Dottorato di Ricerca. Università degli Studi Tuscia di Viterbo, Dipartimento di Produzione Vegetale, Sezione Ortofloroarboricoltura. 2005. P. 7.

6. Dardanello, Ferruccio. “IGP Nocciola Piemonte: Relazione Storico – Tecnico – Economica.” Camera di Commercio Industria Artigianato e Agricoltura di Cuneo, Allegato n. 7. December 20, 1993. (In support of PGI application, Dossier No.: IT/PGI/0117/0305.) P. 1.

7. Casalis, Goffredo. Dizionario Geografico – Storico – Statistico – Commerciale – degli Stati di S.M. il Re di Sardegna, Vol. XVII. Turin. Presso Gaetano Maspero. 1848. P. 169.

8. Dardanello, 2.

9. The impact of Fascism on Italian agriculture must also be considered. Though Mussolini was less aggressive than he ought to have been in addressing food production, autarky and austerity pressured Italians into producing food however they could. With land reclamation and inefficient use of prime agricultural lands due to Mussolini’s “Battle for Grain,” it was natural to turn to the dry, rough hills of Piedmont that had historically proven ideal for hazelnuts.