Though Gianduia remained both puppet and political symbol through the 1860s, the character adopted a new function. Gianduia became the central figure in Turin’s celebration of Carnival—the setting for the probable first appearance of the confection that would come to bear his name.

In 1861, Turin reached its political peak as the seat of government for the newly formed Kingdom of Italy. With swelling civic pride, a group of prominent citizens banded together near the end of the following year to form the Society of Gianduia, with the principle goal of organizing and expanding Turin’s Carnival celebration (1). The Society was chaired by Count Ernesto di Sambuy, “one of the last great aristocratic public figures in Turin” (2).

Marco Minghetti (Giuseppe Saredo, 1861)

Before the Society’s plans for carnival could be fully implemented, a treaty was signed on September 15, 1864, between the nascent Italian government and Napoleon III—the September Convention. The treaty required that Italy respect the territorial sovereignty of the (still independent) Papal States, assume a proportional amount of the Pontifical debts relating to territories annexed by Italy, and take no action against the organization of a Papal army, in return for which France agreed to a staged withdrawal of troops from the Papal States. Additionally, to help assuage Papal fears that the Italian government intended to remain in Turin and promptly annex the Papal States (after which Rome would be made the capital), the September Convention included a secret, unpublished protocol that made the treaty conditional on the Italian government leaving Turin for elsewhere in Italy within six months (3).

Piazza San Carlo (Turin)

Less than a week after the September Convention was signed in Paris, news of the secret protocol spread through the streets of Turin. Upon learning that the capital was to be removed to Florence, the public began protesting immediately. Fearing for his safety, Prime Minister Marco Minghetti (who had negotiated the treaty) brought in gendarmes from surrounding towns. On the afternoon of September 21, gendarmes rushed an assembly in Piazza San Carlo, beating and sabering until the crowd dispersed. Later that evening, the protest resumed at the Ministry of the Interior and was dispersed by pointblank volleys, leaving 57 dead and many wounded. The following day, gendarmes and infantry fired into a dense crowd in Piazza San Carlo, leaving over 100 dead (4).

Sensing revolution, King Vittorio Emanuele II dismissed his entire Cabinet on September 23, 1864—only eight days after the signing of the September Convention. Nonetheless, the Italian Parliament approved the treaty in early October and the transfer of offices from Turin began at once. Fearing for his personal safety, Vittorio Emanuele also swiftly departed for Florence (5).

Fiera di Torino (Casimiro Teja, in Pasquino, No. 7, February 18, 1866)

A few months after the upheaval of public riots and the transfer of governance from Turin, the Society of Gianduia oversaw the city’s revamped carnival in 1865. Entertainment came in the form of masquerades, fireworks, and a wine exhibition (6). Responding to high unemployment, the city contributed 5,000 lire to the Society of Gianduia to host a benefit ball for unemployed workers and the families of the September massacres (7). The success and popularity of the effort led to expansion in 1866 to additional plazas and parade routes. A wine competition was added in 1867 (8). In the closing years of the decade, a wine lottery, livestock competition, and exposition of regional products and foods were added. A special jury issued awards to noteworthy wines, livestock, parade crews, and exhibition booths (9).

The character Gianduia featured prominently in all of these celebrations, in theater, song, and public appearances. The Society of Gianduia announced and promoted the celebrations months in advance in the Gazzetta del Popolo and (beginning in 1867) the Gazzetta Piemontese, issuing a series of bulletins (sometimes thirty or more) under the name of Gianduia. The culmination of the celebrations was the Fiera Fantastica di Gianduia. The Jury of Gianduia issued medals featuring the likenesses of Gianduia and Giacômëtta.

Gianduia and Giacômëtta (Dalsani, in Il Diavolo, No. 28, March 6, 1867)

The popular poet and songwriter Cesare Scotta penned a number of celebratory songs in Piedmontese that show the depth of local identification with the mask. Inspired by a lengthy, pseudo-Homeric poem of the same name (by Fra Chichibio, published in Il Fischietto), Scotta wrote “La Giandujeide,” portraying the life of Gianduia. The poem was performed in Piazza Vittorio during the 1868 carnival, with Scotta playing the role of the adult Gianduia. In a shorter song of the same title, Scotta penned the following chorus, repeated after every stanza:

“We sing / We shout / Suckling from the jug / Lifting the goblet / Hurray for Gianduia / And his Giandujot.” (10)

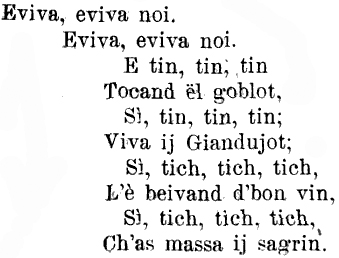

In “Ij Fieuj d’Gianduja” (i.e., “The Children of Gianduia”) Scotta wrote:

“Hurray, hurray for us! / Hurray, hurray for us! / And ding, ding, ding / Touching the goblet / Yes, ding, ding, ding / Long live the Giandujot / Yes, clink, clink, clink / It’s by drinking good wine / Yes, clink, clink, clink / That you kill your troubles.” (11)

In these and other songs, Scotta referred to the people of Turin and Piedmont as Giandujot, the plural diminutive of Gianduia. The songs portrayed the Turinese as Gianduia’s children—jovial, carousing, patriotic, and thirsty for wine. The Giandujeide became a recurring feature of Turin’s carnival celebrations until 1893.

However, Gianduia’s greatest role in Turin’s 1865 carnival was not as a celebratory figure, but as a political reconciler. During the celebrations of Sunday, February 26, King Vittorio Emanuele II returned to Turin to witness the spectacle. Riding in an open carriage through Piazza San Carlo—the scene of two post-September Convention massacres less than five months previous—Federico Dogliotto, on horseback, blocked the king’s path.

Dogliotto appeared in the guise of Gianduia, in shirtsleeves, but with the characteristic tricorne and pigtail. Carrying the flag of the Kingdom of Italy (i.e., the Italian tricolor with the shield of the House of Savoy), Gianduia approached the king, proclaiming, “See how I have given my coat? But, if necessary, I will give even this scrap of shirt for your good and that of Italy.” Vittorio Emanuele II, moved by the gesture, reached out to take Gianduia’s hand. Felice Cerruti Bauduc’s lithograph depicting the symbolic handshake (pictured at the top of this item) circulated widely through Piedmont, cementing the loyalty of the “children of Gianduia” to Vittorio Emanuele II and the Kingdom of Italy (12).

It is in this setting—Turin’s carnival of 1865—that gianduiotti allegedly first appeared.

Notes:

1. Torricella, Giuseppe. Torino e le sue Vie, Illustrate con Cenni Storici. Tipografia di Giovanni Borgarelli. Turin. 1868. Pp. 182-3.

2. Cardoza, Anthony L. Aristocrats in Bourgeois Italy: The Piedmontese Nobility, 1861-1930. Cambridge University Press. 1997. P. 117.

3. O’Clery, Patrick Keyes. The Making of Italy. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, & Co., Ltd. London. 1892. Pp. 340-3.

4. O’Clery, 343-5.

5. Dicey, Edward. Victor Emmanuel. Marcus Ward & Co. London. 1882. P. 283.

6. Torricella, 183.

7. Bracco, Giuseppe. “Il Cioccolato nella Città di Gianduia,” in Il Cioccolato: Industria, Mercato e Società in Italia e Svizzera (XVIII-XX Sec.). FrancoAngeli. Milan. 2007. P. 15. Also, Gianeri, Enrico. Gianduja nella Storia, nella Satira. Famija Turineisa. Turin. 1962. Pp. 98-9.

8. Gianeri, 99.

9. Gazzetta Piemontese (now La Stampa), February 9 and 14, 1869. We will soon return to the issue of jury prizes.

10. Scotta, Cesare. (Trans. Kevin McCabe.) Cansson Piemonteise Edite e Inedite d’ Cesare Scotta. Stamparia Nassional d’ Botero Luis. Turin. 1868. P. 177.

11. Scotta (Trans. Kevin McCabe), 180.

12. Ricci, Matteo (ed.). Scritti Postumi di Massimo D’Azeglio, a Cura di Matteo Ricci. G. Barbera, Editore. Florence. 1871. P. 447.