Unlike the development of a beet sugar industry, Napoleon’s second contribution to gianduia’s invention was not an outgrowth of the Continental System. In fact, the policy predated the Berlin Decree by more than a decade. In the closing years of the eighteenth century, Napoleon extended unprecedented civil rights to the Waldenses in Piedmont.

The original Waldenses (also Vaudois or Valdese) are traced to Valdesius (or Waldo or Valdes) of Lyon, a twelfth-century merchant who, in a fit of conscience, sold all he owned, gave to the poor, and began preaching and gathering followers, who came to be known as the “Poor of Lyon.”

The voluntary assumption of poverty and public teaching by laity raised concerns among Catholic authorities. Varying accounts from the Third Lateran Council of 1179 relate that Valdesius and his followers were judged schismatics or, less harshly, ordered to desist from public preaching unless otherwise instructed by their priests (1). This begrudging tolerance ended in 1184 with the Council of Verona, under Pope Lucius III, in which the Waldenses were anathematized. Continuing concern with unauthorized preaching by the Waldenses led to expanded denunciation in the Fourth Lateran Council, under Pope Innocent III (2).

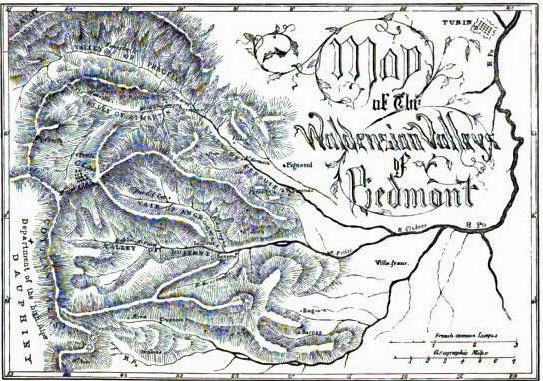

Map of the Waldensian Valleys of Piedmont (from The Waldenses; William Beattie, 1838)

Between 1182 and 1184, Archbishop Jean Bellesmains expelled the Waldenses from Lyon. The Waldenses’ illiteracy contributed to the lack of documentary evidence of their movements in this early diaspora. However, in 1205, two groups of the “Poor” began drawing the attention of Catholics in the Italian peninsula: the “Poor Leonists” and the “Poor Lombards.” By the early 1300s, Waldensian populations were firmly ensconced in the eastern and western valleys of the Cottian Alps—including, on the Piedmontese side, Val di Susa, Val Chisone, and Val Pellice.

Though Catholic writers labeled these people “Waldenses,” it remains unclear what, if any, connection or continuity the Piedmont populations had with the original Poor of Lyon (3). Analysis of Piedmont Waldensian beliefs in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries reveals a mildness of heresy comparable to that of the original Poor of Lyon, with unauthorized preaching remaining a bone of contention (4). Mildness notwithstanding, “from the 1230s onwards the life of religious movements deemed heretical was increasingly dominated by the fact of ecclesiastical inquisition” (5).

In the early fourteenth century, Bernard Gui, Inquisitor of Toulouse, included a chapter on the Waldenses in his Practica Inquisitionis Heretice Pravitatis (i.e., Conduct of Inquisition into Heretical Wickedness), based on his experience with the Waldenses of Occitan France (6). (Gui famously appears as a character in Piedmont-born novelist/semiotician Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, which is conjecturally set “along the central ridge of the Apennines, between Piedmont, Liguria, and France” in the midst of a tangle of orders and heresies involving apostolic poverty, including Waldensianism (7).)

Sacra di San Michele, Val di Susa

Shortly after Gui completed his Inquisitor’s Manual, Inquisition commenced in Piedmont under Alberto di Castellario in 1335 (8). Though Cathars were the primary quarry, Alberto uncovered Waldsenses in Giaveno, in Val Sangone (9). Subsequent efforts targeted other Waldensian valleys. Tommaso di Casasco led the inquisition of Val di Lanzo in 1373. Antonio di Settimo di Savigliano, based in Pinerolo, combed through western Piedmont in 1387-9, after Pope Gregory XI complained to Amadeo VI of Savoy of the openness with which heretics lived and proselytized in Piedmont (10). Fra Giovanni di Susa operated in Carmagnola for nearly two decades. As late as 1491, a papal bull was issued authorizing Angelo Carletti and the bishop of St-Jean-de-Maurienne to lead an armed crusade against the Waldenses of the eastern valleys (11).

When Cattaneo was authorized by papal bull in 1487 to root out heresy in the Dauphiné, Savoy, and Piedmont, he led a bloody crusade on the Waldenses of the Dauphiné (in the western valleys), resulting in the deaths of 160 suspected Waldenses by burning, hanging, and being thrown off of cliffs (12). Though not directly impacting the Piedmontese Waldenses, the abuses of the crusade in the Dauphiné contributed to a gradual turn of sentiment against the Inquisition.

Inquisitorial treatment of Waldenses for the better part of two centuries showcased the full spectrum of excesses associated with the institution—torture, extortion, expropriation, and executions. Though Waldenses in France fared poorly, persecution strengthened the Piedmont Waldenses, fostering an internal cohesion in the communities that would serve them well as they faced subsequent trials (13).

Waldensian Church at Bobbio Pellice, Val Pellice (from The Waldenses; Beattie, 1838)

By the mid-sixteenth century, most of the Waldenses united with Swiss Calvinists in the Reformation, though the Waldenses of the lower valleys in Piedmont maintained their own identity (14). In 1560, Emanuele Filiberto, Duke of Savoy, sought to restore control over the Waldensian valleys with the Edict of Nice, prohibiting and penalizing the hearing of Protestant preaching. When it became apparent the Edict was being ignored by the Waldenses, the Duke ordered military forces into the valleys. In a series of mountain skirmishes, the Waldenses repelled the Duke’s forces, resulting in the 1561 Treaty of Cavour, which accorded the Waldenses a limited right to exercise of their religion (15).

Nearly a century later, Carlo Emanuele II (great grandson of Emanuele Filiberto) renewed persecution. In 1655, the Duke assembled an army of 4,000 against the Waldenses. Recognizing the impossibility of effective resistance, the Waldenses sent emissaries to assure the duchy of their submission. In April, the Marquis of Pianezza ordered the Waldenses to house the army, receiving reluctant acquiescence. The military occupation of Waldensian villages rapidly devolved into a widespread massacre known as the Pasque piemontesi (i.e., the Piedmont Easter), with refugees fleeing into France and Switzerland (16). News of the massacre and dispersal reached England and made the Waldenses a cause célèbre, prompting a national fast, collection of donations for support of the survivors and refugees, and a sonnet by John Milton, “On the Late Massacre in Piedmont” (17).

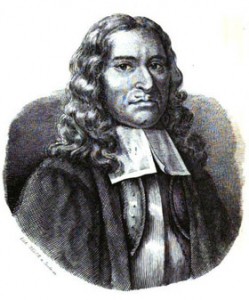

Henri Arnaud (from Histoire de l'Église Vaudoise, Vol. 1; Antoine Monastier, 1847)

In 1689, many exiles returned to Piedmont from Switzerland under the leadership of Henri Arnaud, in what the Waldenses refer to as “the Glorious Return.” The following decade offered little respite. In 1697, the duchy of Savoy expelled over 3,000 Waldenses from Val Chisone, only permitting resettlement when war with France made the Waldensian presence expedient to Savoy.

The duchy continued to devise repressive measures in the early eighteenth century. An edict in 1716 forbad assemblies of more than ten Waldenses in a single location. A 1721 decree required that all newborn babies (including those of the Waldenses) be baptized Catholic (18). Protestantism was banned outright in 1730 (19).

Pinerolo by Moonlight (from The Waldenses; Beattie, 1838)

In 1739, the Savoyard Royal Society began offering generous loans for land purchases, provided the borrower was either a Catholic purchasing Waldensian land or a Waldensian abjuring his heresy and joining the Catholic fold. The administration built a school in Pinerolo in 1743 for compulsory Catholic education of Waldensian youth (20). The remaining Waldenses in Piedmont found that “the valleys had become a ghetto” (21).

On March 2, 1796, the twenty-six-year-old Napoleon Bonaparte was named Commander in Chief of the Army of Italy. Despite considerable numerical superiority of the enemy, within two weeks of taking command in the field Napoleon severed lines of communication between the Piedmontese troops and their Austrian allies, marched on Turin, and negotiated the Armistice of Cherasco, dislodging the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia from the First Coalition and securing the Army of Italy’s rear and flank (22).

Luserna San Giovanni (from The Waldenses; Beattie, 1838)

Later that year, the Waldenses appealed to Carlo Emanuele IV with a number of requests for expanded civil liberties (e.g., the right to hold elected office, elimination of required contributions to the expenses of the Catholic Church, the right to establish a school in San Giovanni, etc.), all of which were either flatly refused or indefinitely deferred for further consideration (23).

By spring of 1797, Napoleon’s continued success in the campaign, culminating in the Treaty of Leoben, made it clear that the French and their revolutionary principles would not soon be gone. Carlo Emanuele reversed himself with a decree in July that freed the Waldenses of required contributions for expenses of Catholic worship, eliminated prohibitions on holding elective office, ensured equal taxation between Waldenses and Catholics, and permitted the Waldenses to repair existing churches and build new ones (24).

Russian and Austrian success in northern Italy in late 1799 threatened the improved conditions of the Waldenses, who by this point had energetically thrown in their lot with the French. However, within eight months, Napoleon had returned from Egypt, become First Consul, led the Army of the Reserve through the Great St. Bernard pass, defeated the Austrians at Marengo, and restored French control over the territory (25). This proved decisive for the Waldenses.

As Tourn writes, “The revolution led to the Napoleonic Empire, and in that context the ghetto disappeared for good, both as a juridical and a social reality. New Empire laws recognized the right of all citizens to the religion of their choice, freely and without discrimination. Lands which for centuries Waldenses had cultivated only as young hired hands could now be bought. Valley merchants could at last think of expanding their commerce…. The hated ‘Hostel for Waldensian Catechumen’ was closed, and with it the pervading fear that their children would be kidnapped and brought up as Catholics” (26). With French control restored, England withdrew its financial support from the Waldenses. The French administrator for Piedmont promptly replaced the funding—an action later ratified by Napoleon personally (27).

With the fall of Napoleon and return of Vittorio Emanuele I, a measure of persecution returned. When Napoleon escaped from Elba and returned to Paris, the king moderated his stance towards the Waldenses, recognizing the possibility of renewed Waldensian collaboration with the French (28).

Carlo Alberto (from Vita di Carlo-Alberto; C. Augusto Vecchi, 1851)

In February of 1848, Carlo Alberto, King of Piedmont-Sardinia, approved a constitution (the Statuto) heavily influenced by the Napoleonic Code and issued letters-patent that expressly conferred full and equal civil and political rights on the Waldenses (29). Carlo Alberto’s liberal attitudes towards the Waldenses were shaped by his youth and education in Paris and Geneva during the Napoleonic era (30). An early and persistent Francophile, Carlo Alberto had even served under Napoleon, being appointed a lieutenant of dragoons at the age of sixteen (31). Though some prejudice and discrimination against the Waldenses lingered after the new constitution, Carlo Alberto made permanent many of the revolutionary ideals brought to Piedmont by Napoleon a half century before.

Civil rights under the Napoleonic Code and the Statuto paved the way for Waldenses to leave their valley refuges and seek opportunity in the plains of Piedmont and the capital city of Turin. This was key because, as we shall see, Waldenses came to play a crucial role in the industrialization of chocolate-making in Turin. More to the point, Waldenses invented gianduia.

Notes:

1. Cameron, Euan. Waldenses: Rejections of Holy Church in Medieval Europe. Blackwell Publishers, 2000. P.17.

2. Cameron [2000], 21.

3. Cameron, Euan. The Reformation of the Heretics: The Waldenses of the Alps, 1480-1580. Clarendon Press, 1984. Pp. 7-11.

4. Ibid., 68.

5. Cameron [2000], 63.

6. Cameron [2000], 92-3

7. Eco, Umberto (trans. William Weaver). The Name of the Rose. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 1994. Pp. 3-4.

8. Audisio, Gabriel (trans. Claire Davison). The Waldensian Dissent: Persecution and Survival, c. 1170 – c. 1570. Cambridge University Press, 1999. P. 40.

9. Lambert, Malcolm D. The Cathars. Blackwell, 1998. P. 290.

10. Cameron [1984], 26.

11. Cameron [1984], 26.

12. Cameron [1984], 32.

13. Cameron [2000], 67.

14. Cameron [1984], 155-66.

15. Cameron [1984], 155-66.

16. Audisio, 205.

17. Audisio, 206.

18. Tourn, Giorgio (trans. Camillo P. Merlino). The Waldensians: The First 800 Years (1174 – 1974). Claudiana, 1980. P. 158.

19. Audisio, 211.

20. Tourn, 162.

21. Audisio, 211.

22. Chandler, David G. The Campaigns of Napoleon. Scribner, 1973. Pp. 63-76.

23. Muston, Alexis. The Israel of the Alps: A History of the Persecutions of the Waldenses. Ingram, Cooke, & Co., 1853. P. 280.

24. Ibid., 281.

25. Chandler, 253-98.

26. Tourn, 169.

27. Muston, 286.

28. Muston, 288-9.

29. Homer, Michael W. “New Religions in the Republic of Italy,” Regulating Religion: Case Studies from Around the Globe (ed. James T. Richardson). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2004. Pp. 204-5. Audisio, 211-2.

30. Duggan, Christopher. The Force of Destiny: The History of Italy Since 1796. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008. P. 84.

31. Godkin, G.S. Life of Victor Emmanuel II: First King of Italy. Macmillan & Co., 1880. P. 8.