Most of the information presented to this point has been publicly available, at least for those with enough interest to seek it out. As a practical matter, only some specialty retailers, chocolate makers, and serious fine chocolate consumers have been aware of it. For many observers, that circumstantial evidence is more than enough to convince them that the Masts were not on the up-and-up in their first couple of years in business. Others may require more direct proof.

(After repeated requests to Rick Mast for an interview at a time and place of his choosing, his public relations representative declined on his behalf.)

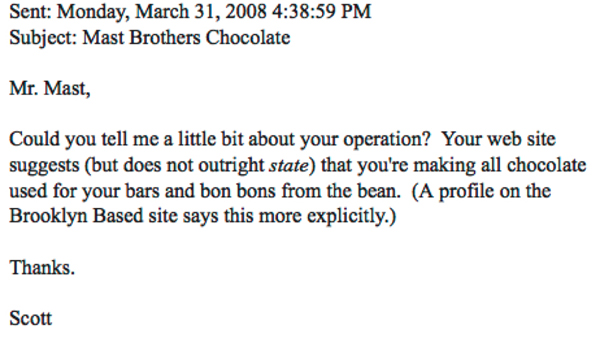

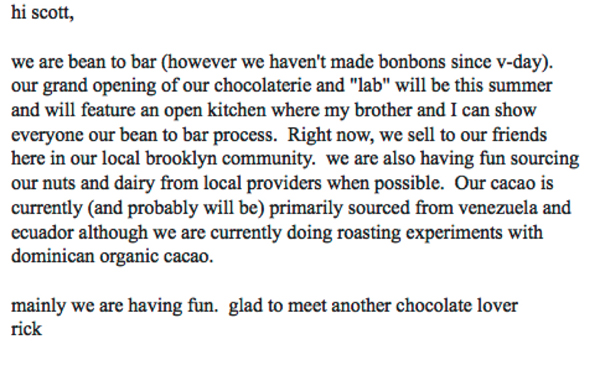

Back in early 2008, after trying several Mast Brothers bars and disbelieving that they had made the chocolate, I had a brief email exchange with Rick Mast. On March 31, I wrote:

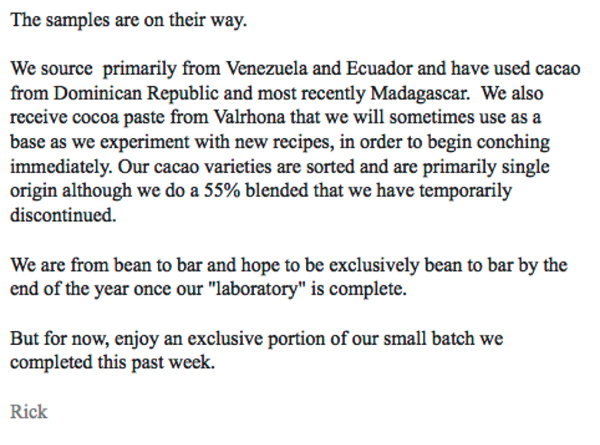

On April 3, Rick Mast responded:

Notwithstanding the ebullient tone, Mast failed to offer any substantive detail about their operation and neatly sidestepped the question about whether they were making all chocolate from the bean. So, I asked again, more directly:

Notwithstanding the ebullient tone, Mast failed to offer any substantive detail about their operation and neatly sidestepped the question about whether they were making all chocolate from the bean. So, I asked again, more directly:

Rick Mast never responded. Though not an admission, I construed Mast’s evasion and then silence, combined with the evidence of my senses in tasting the chocolate, as an answer.

Masts at the flea market (June 29, 2008)

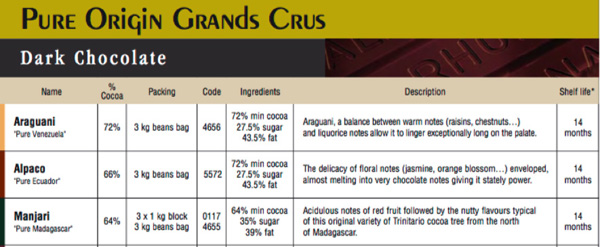

Months later, in late June of 2008, Art Pollard was in New York City for the Summer Fancy Food Show. Along with Clark Goble, Pollard had founded Amano Artisan Chocolate (in 2006), one of the premier craft chocolate makers in the United States. On the weekend, Pollard visited the Brooklyn Flea with a small group (including a member of the Manhattan Chocolate Society), where he met the Mast Brothers peddling their bars. He scanned the range of products on the table while talking chocolate with Rick Mast, when he saw a couple of bars that surprised him: a dark milk chocolate and a Trinidad single-origin bar. Pollard had experimented with making milk chocolate, but was unable to get whole milk powder of an acceptable quality without committing to a minimum order far beyond his needs. Likewise, in trying to find cacao sources in Trinidad, he had run into dead ends. Cacao production in the country was low—the workers drawn away from cacao plantations to more lucrative oil field work—and nearly all of that was under contract to major French and Italian makers. Impressed and curious, he asked, “Where were you able to get cacao in Trinidad?” Rick Mast replied, “Oh, these three we make,” pointing to the flavored bars of unspecified cacao origin, “and the other three are Valrhona,” referring to the single-origin bars and dark milk chocolate.

In a discussion thread on The Chocolate Life website in April of 2009, someone with the username “Fortnum” asked: “Can anyone confirm that they KNOW the Mast Brothers are actually manufacturing chocolate from bean to bar? Several things I have seen here and there have made me really doubt it. I would like to be sure.” Pollard responded: “I have spoken with the Mast Brothers. They were up front with me that some of their chocolate they make and some they do not. If you ask them specifically, they will tell you which is which; but, unfortunately, it isn’t always very clear from their advertising/statements that some of their chocolate is made elsewhere or is a blend. They are using Santha class machines. Nice guys.”

Mast Brothers, February 2008

In the summer of 2008, Betty Hallock was researching and interviewing for a Los Angeles Times article on the rise of small bean-to-bar chocolate makers in the United States, including Mast Brothers. When Hallock heard whispers of the Masts’ remelting, she asked them about it. According to Aubrey Lindley (co-owner of Cacao, in Portland, Oregon), who spoke with her during her preparation of the article, Hallock said Mast Brothers admitted to her that they were remelting for some of their products and indicated that they planned to go entirely bean-to-bar once their new factory opened. In the final article, Hallock made only passing mention of “a couple of cocoa-loving brothers [who] are building a ‘chocolaterie and laboratory’ in the south Williamsburg neighborhood” of Brooklyn, included no quotes from the Masts, omitted the Masts from a sidebar company listing of “Chocolate Made in America,” and instead focused the article on several established and unquestionably bean-to-bar makers (“Think chocolate can’t get any better?” LA Times, July 16, 2008). (At time of publication, Hallock received, but did not respond to, multiple requests for comment made over a one-month period. She has since confirmed the reporting.)

Rick Mast began corresponding with Alan McClure, the founder of Patric Chocolate and one of the most highly regarded craft chocolate makers in America, in spring of 2008. Having heard rumors of the Masts’ remelting, in a phone conversation in late 2008 McClure asked Rick Mast directly whether there was any truth to it. Mast acknowledged that they had used Valrhona for some products, but assured him that it was all in the past and that they had gone fully bean-to-bar.

There’s a pattern to these accounts, with Rick Mast’s reluctant admission in private, claims of using Valrhona, and insistence that he and his brother were making at least some chocolate. Only later did I learn that Rick Mast had followed the same pattern in correspondence with the friend who sent me Mast Brothers bars in early 2008. When Larry Gober, a chef in Tulsa, Oklahoma, enquired about mail order availability of Mast Brothers chocolate, on February 28, 2008, Rick Mast offered to send some bars: “We are more interested in perfecting our craft and getting feedback from those as passionate as us about chocolate…. The only thing we ask in return is for you and your friends to give us your HONEST opinion. We can take it.”

Gober replied by email on the same day, thanking Rick, and asking: “Quick question, what chocolate are you sourcing? Are you doing single origin or blending? Are you doing from bean to bar?” The following afternoon, Rick Mast responded:

Mark that. After nearly six months of selling to the public, Rick Mast expressed a hope that the Mast Brothers would be “exclusively bean-to-bar” in another ten months. Despite copping to remelting, Mast disingenuously professed that “we are from bean to bar.” At the risk of stating the obvious, that’s not how it works. You don’t operate a gluten-free bakery, if you merely hope to eliminate gluten from your baked goods at some future date. If you have meat on your menu, you don’t run a vegetarian restaurant. To claim otherwise is to lie. Yet less than one week ago, in response to questions from Grub Street about the first two reports in this series, Rick Mast doubled down on that lie, breezily reassuring the press and public that, “Needless to say, we were then and are now a bean to bar chocolate maker.”

Several times throughout 2008, the Masts privately confessed that they were remelting. However, in public, with their customers, and to the press (apart from Betty Hallock), they presented themselves solely as bean-to-bar makers, even hypocritically contrasting themselves with remelters. (“Unlike the many chocolatiers who use couverture—discs of premade chocolate that can be remelted for confections and bars—Rick and Michael Mast count themselves among a small cadre of artisans who make their chocolate from cocoa bean to bar” [“A Brotherly Love of Chocolate,” New York Sun, April 16, 2008].)

That smacks of fraud. It doesn’t matter whether all or some lesser percentage of the chocolate the Masts sold was remelted. The scandal is that that any of it was, just as it would be if Tiffany & Co. substituted cubic zirconia in any diamond engagement rings. That said, the remelting appears to have been substantial and to continue well beyond Rick Mast’s early target date for his company to end the fakery.

In spring of 2008, Brady Brelinski visited the Mast Brothers’ table at the Brooklyn Flea, where he spoke with the brothers, and—after hearing they were making their chocolate from the bean—purchased three single-origin bars. He brought the bars to a Manhattan Chocolate Society tasting on April 20, where the tasters were favorably impressed by the chocolate quality.

The three Mast Brothers bars were Ecuador 66%, Venezuela 72%, and Madagascar 64%. The percentages and origins exactly matched those of three of Valrhona’s single-origin couvertures from that year’s product catalog: Alpaco (Ecuador 66%), Araguani (Venezuela 72%), and the old warhorse Manjari (Madagascar 64%).

By Rick Mast’s admission to Art Pollard in mid-summer of 2008, at least half of the bars they were selling that day were remelted. Customers who purchased Mast Brothers’ Trinidad single-origin bars were likely getting Valrhona’s Gran Couva. But if the single-origins and dark milk chocolate at that time were faked, as the Masts had indicated, is it probable that they were making the dark bars of unspecified cacao origin from the bean? It strains credibility to imagine that the Masts would source cacao, make chocolate from it, conceal the geographic origin and percentage of cacao solids, and use it in a flavored bar.

Handmade Holiday Craft Fair (December 7, 2008)

Near the end of 2008, as the brothers moved into their CBVL period, the picture became even more troubling. Following more than a year of inexplicable nondisclosure of ingredients to consumers, bar after bar was revealed to include the “dumbed down” ingredients the Masts insist they eschewed in their bean-to-bar production from the beginning: cocoa butter, vanilla, and soy lecithin. This was not a onesy-twosy thing. Scores of photos from social media (dated or date-checked with metadata), images and ingredient lists from retailers’ web sites and blogs (via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine), and reviews and notes from meticulous chocophiles show nothing but that formulation, until the appearance of some early two-ingredient labels in May of 2009. Indeed, because of the amount of product the Masts pushed onto the market, many of their bars with cocoa butter, vanilla, and soy lecithin appeared on shelves well into 2010. (In a visit to New York City in January of 2010, CBVL-phase bars were all I could find at Murray’s Cheese and Dean & DeLuca.)

Manhattan Chocolate Society (March 21, 2009)

On March 21, 2009, a half-dozen members of the Manhattan Chocolate Society visited the Mast Brothers’ North 3rd Street store for a tour led by Rick Mast. The Masts’ transitional equipment was present and there were some signs of chocolate-making on a small scale. However, underneath a counter in the factory, Brady Brelinski and George Gensler also observed containers of fèves—the distinctive, thumbprint-shaped form of Valrhona’s couverture. They did not see vanilla beans, bulk cocoa butter, or soy lecithin (liquid or powder) in the shop, nor did they hear Rick Mast mention the use of those ingredients in the Masts’ chocolate-making process. While in the shop, they picked up three Mast Brothers bars for a tasting later in the day: a 75% with nibs (of unspecified cacao origin), a 60% dark milk chocolate (of unspecified cacao origin), and a 75% Dominican Republic. The ingredient list for each bar included cocoa butter, vanilla, and soy lecithin.

The Masts affirm that they were two-ingredient chocolate makers from the beginning; but, for over six months, the chocolate they sold had ingredient labels showing added cocoa butter, vanilla, and soy lecithin. Most industrial couverture (including from Valrhona) includes added cocoa butter, vanilla, and soy lecithin. The Masts repeatedly admitted, in private, that they used industrial couverture in their bars. It’s easy enough to connect the dots, even without considering the sensory evaluations of experienced chocolate tasters or the output limitations of the Masts’ equipment. In their first two years, the Masts appear to have built their company and their reputation largely on mountains of chocolate that they did not make.

Some may contend that this is all ancient history—that, whatever the Masts’ indiscretions in their first two years, they did eventually open their shop to the public, scale up the equipment, order cacao in serious quantities, and fully become what they had pretended to be. But trust is vital in the chocolate business. As a cranky old chocophile once wrote, “Not that you lied to me, but that I no longer believe you, has shaken me.” Now the Masts are in the midst of another transition. They’ve taken on a partner to help fund their growth and are currently making the rounds soliciting substantial private equity investment for an even greater expansion. At the same time, they’re becoming less transparent about their operations and, therefore, demanding more confidence from their customers.

Mast factory makeover (photo by Dean Kaufman)

The recent remodel of the Masts’ 111 North 3rd Street shop, closely matching the look and function of their London boutique, drastically reduced its production capacity, removing all but eight grinders (with three of them attractively framed by picture windows). According to two Mast employees (who asked not to be identified by name), the grinders are primarily for demonstration and display purposes, as nearly all production has been shifted to the Masts’ factory at 46 Washington Avenue, near the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The Navy Yard factory has remained closed to the public. To a request about the possibility of a paid private tour, Diana Donohue, Brooklyn General Manager for Mast Brothers, declined and responded that, “At this time we do not offer tours of the factory on Washington Avenue.”

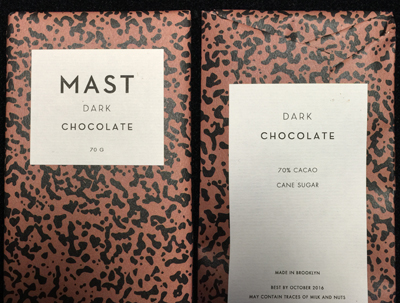

Mark Christian (of the C-spot) says, “I’ve told Rick and Mike to their faces, ‘You guys are not in the chocolate business; you guys are in the wallpaper business.’ They’re kind of sensitive to the criticism; but at the same time, they’re very astute. They’re doing business right now. They’re not doing chocolate. Chocolate is just a vehicle to the business. The wallpaper is part of that. They understand it.” Consistent with Christian’s contention, the brothers recently released their “2016 Collection,” devised by their in-house Creative Director, Nathan Warkentin, a former menswear designer. Joining the Masts in 2012, “Warkentin has been actively taking elements off the bars’ labels ever since, ditching long descriptions of provenance in favor of straightforward ingredient lists and letting the packaging patterns speak a bit more loudly instead” (“The Influences of Mast Brothers Creative Director Nathan Warkentin,” Sight Unseen, Monica Khemsurov).

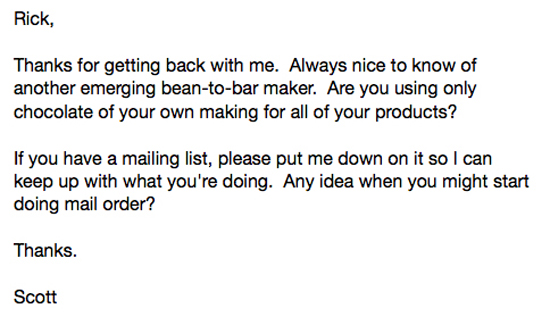

New Mast bar (without statement of origin)

The Masts’ did not merely pare back the descriptions of provenance. They eliminated them. Of the twelve bars in the new lineup, none specifies the cacao’s source or country of origin. In their book, the Masts declared that one of the seven guiding standards for their “principled growth” was to “Connect customers to the source. We are nothing without our farmers. In every way possible, we must pay tribute to them and share their work” (MBC, 5). Yet, with this move, they have entirely effaced the farmers, commodifying cacao in the same fashion as the industrial giants of chocolate. Let that sink in for a moment. Without stating the cacao origin, the Mast Brothers are free to use absolutely any cacao they can get their hands on, at any price, in any bar. Without knowing the origin, a customer has no way of assessing the probable quality of the cacao, the environmental sustainability of its production, the fairness of pricing for the farmers, or the absence of abusive labor practices (e.g., child slavery). (Additionally, none of the bars includes any trade or organic certification for any ingredient.) Customers and retailers concerned about such matters will not be content to admire the latest wallpaper designs, while trusting the Masts’ undisclosed sourcing decisions. Implicitly, the Masts bank on indiscriminate buyers for whom the packaging is the product.

Touting the Mast Brothers’ transparency in a 2010 radio interview with Jessica Harris, Michael Mast proclaimed, “That’s why we’re so open about what we’re doing and how we have an open factory, so people can really see what’s going on, and there’s no mystery behind it, and there’s no mystery in the ingredients or the process” (“From Scratch,” NPR). The Masts have now turned their backs on all of that, returning most of their production to the “black box” and enshrouding their ingredients in mystery.

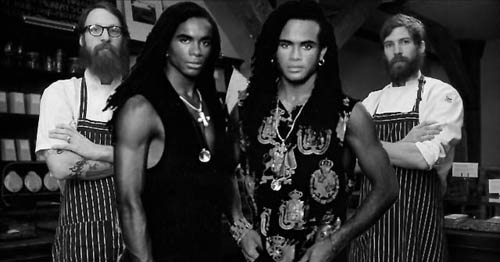

In 1989, two photogenic young men styled their hair with matching ostentatious braids, posed on an album cover, stood behind microphones, and moved their lips. Their album held the top spot in the Billboard Top 200 for eight weeks, spawned three #1 hits, earned a Grammy for “best new artist,” and sold over seven million copies. It all came crashing down when their producer revealed that Rob Pilatus and Fab Morvan did not sing a single note on the album.

In 1989, two photogenic young men styled their hair with matching ostentatious braids, posed on an album cover, stood behind microphones, and moved their lips. Their album held the top spot in the Billboard Top 200 for eight weeks, spawned three #1 hits, earned a Grammy for “best new artist,” and sold over seven million copies. It all came crashing down when their producer revealed that Rob Pilatus and Fab Morvan did not sing a single note on the album.

Rick and Michael Mast were the Milli Vanilli of chocolate. They costumed themselves with quaint clothing and showy beards. (In the fall of 2008, Michael Mast even dyed his hair and beard red to better match his brother in photographs.) They talked the talk of authenticity and “reconnecting” the public to lost foodways. By May of 2008, they publicly proclaimed themselves the “Leaders of the Chocolate Revolution.” They won over celebrity chefs, then piggybacked on their credibility. Packaging trumped product. They crafted their public image magnificently. To this day, you can’t read an article about the Masts that doesn’t effuse about the beards and the paper. (When they calculate optimal media-ripeness, count on the beards to be shaven, generating more Mast mania!)

Though an appealing façade, the early Mast Brothers was a Potemkin chocolate factory, churning out remolded, repackaged industrial couverture. With lies that foundational, a cloud of doubt descends on every claim. After the sweeping deception that the Masts made the chocolate that they sold under their family name, even the confessions of using Valrhona must be independently verified. While we can confirm that they remelted some Valrhona, that doesn’t mean they didn’t also use Belcolade (with which Rick Mast became familiar in the weeks he spent “apprenticing” in Jacque Torres’s shop), Callebaut, or other then-common and affordable couvertures. Who really made the chocolate that Dan and David Barber tasted when the brothers visited Blue Hill at Stone Barns in early 2008? Were the many retailers who carried Mast Brothers bars complicit in the charade or were they as clueless as their customers?

It might be satisfying to untangle all of the unanswered questions from the Masts’ early years. However, after learning that Stephen Glass fabricated sources, there’s little point in granular fact-checking of his complete published works. The Masts did not become pariahs in the fine chocolate world because of their beards, publicity, or product mediocrity. It was because of their lies.

[Go to Part 1, Part 2, or Part 3. Supplemental matter will appear on the DallasFoodOrg Tumblr.]