If the first gianduiotto appeared during the politically pivotal 1865 carnival season, it would contribute significantly to the confection’s legend, associating it with Gianduia’s symbolic reconciliation of the Turinese with Vittorio Emanuel II in the interest of the Risorgimento. But did it?

The most common account of the invention of gianduiotti is that Michele Prochet first introduced them during Turin’s 1865 carnival celebrations. At the time, the story goes, the pieces were called by the Piedmontese name givo, only later taking on the name of Gianduia.

As with the 1852 invention myth, most modern accounts of the 1865 appearance of gianduiotti draw—directly or, more often, indirectly—from Cagliano’s February 1932 article in Il Dolce (1). He writes that gianduia “had its official, historical consecration in 1865, in which year Prochet, Gay & Co. began marketing gianduia, popularly known as gianduiotti.”

Cagliano does not cite any source for these claims, though his article clearly relies heavily on information provided to him by personnel of Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. (2). That information includes a hodgepodge of false company lore, such as the 1826 origin of the Caffarel company (3), the alleged apprenticeship of Swiss chocolate luminary François-Louis Cailler under Caffarel in Turin (4), and the 1852 invention of gianduia paste by Michele Prochet (5).

Cagliano does not cite any source for these claims, though his article clearly relies heavily on information provided to him by personnel of Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. (2). That information includes a hodgepodge of false company lore, such as the 1826 origin of the Caffarel company (3), the alleged apprenticeship of Swiss chocolate luminary François-Louis Cailler under Caffarel in Turin (4), and the 1852 invention of gianduia paste by Michele Prochet (5).

Cagliano’s errors and anachronisms about Caffarel history almost certainly flowed from the corresponding ignorance of Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. in the early 1930s. After all, the Caffarel family no longer had ties to the company after 1897 (6). Michele Prochet’s direct knowledge of Caffarel history would have been limited, since he had not even been born at the time Paul Caffarel went into business and was only six years old when Caffarel died (7). Yet when Prochet died in 1904, even that tenuous link with Caffarel history broke. In 1922, the widow of Prochet’s surviving partner sold the company to an unrelated group of investors (8). By the time Cagliano published the article in question, Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. had recently reemerged from bankruptcy with yet another group of owners (9).

Given the numerous changes in ownership and control over the company, Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. in the early 1930s could not be considered a reliable source of information about the previous century’s events. Cagliano’s numerous errors confirm this. If the story of gianduia’s 1865 invention is to be maintained, we must look to older and more reliable sources. Unfortunately, the historical record offers few clues at present.

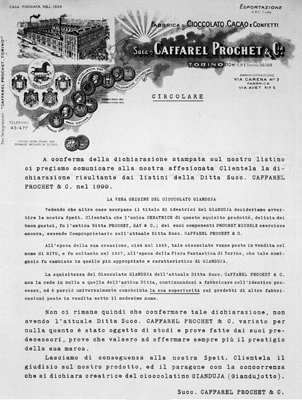

Undated early twentieth century circular from Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co.

The strongest evidence supporting the 1865 invention theory comes in the form of an early twentieth century circular from Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co (10). Though undated, the document was issued at least after 1906 and possibly after 1928 (11). At least four decades (and possibly six or more) had passed since the 1865 carnival. At this point, the Caffarel family no longer had any stake in the business and Michele Prochet had already died (12). Prochet’s surviving partner Ernesto Malan was only eight years old in 1865. Malan’s widow and heir to the company, Noelie Charbonnier, was only two during that key carnival season (13).

Given the intervening decades and multiple changes in ownership, it is unlikely that at the time the circular was published the principals of Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. had any direct knowledge about the invention of gianduia. Perhaps for that reason, the circular purports to reprint an earlier statement by the company, dated in 1899. This 1899 statement provides the substance of the circular, including the claim that gianduia was the original creation of Prochet, Gay & Co. in 1865 (14).

In 1899, Michele Prochet was running Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. He had returned from retirement in 1897 to rescue the company from seven years of mismanagement (15). Though the earliest extant record of Prochet’s operation in Turin is the appearance of Prochet, Gay & Co. in the Guida Commerciale Marzorati-Paravia di Torino in 1866, we cannot preclude the possibility that he was already operating the preceding year (16). If the twentieth century circular accurately transcribes the 1899 statement, its credibility improves considerably, in that Michele Prochet (a) was operating the company at the time the statement was made and (b) was active in Turin’s chocolate industry during the mid to late 1860s.

From Prima Esposizione D'Arte della Città di Venezia, 1895: Catalogo Illustrato

However, the greatest evidentiary strength of the 1899 statement is also its greatest weakness. While Prochet was undeniably in a position to know of which he spoke, he was also quite far from disinterested. At sixty years of age, Prochet was claiming that he invented gianduia over thirty years previously. He claimed this at a time when he was trying to restore the fortunes of Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. after years of mismanagement and accumulated debt. And, as the statement’s text indicates, Prochet staked his claim precisely because other companies at the time were also claiming to have invented gianduia (17).

Though Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. began incorporating the invention claim in its marketing in the early years of the twentieth century (as evidenced by boxes from 1905-6 and publicity cards from 1910), there is no evidence at present indicating that the company (or Prochet) made any such claim prior to 1899 (18). In fact, in 1895, less than five years before Prochet’s first known invention claims, the company merely described gianduia as a “specialty” of the house, in much the same way that Talmone and Moriondo & Gariglio did in the 1890s (19)(20).

Looking at the data dispassionately, all one can conclude from the circular—even if one assumes its authenticity and that of the 1899 statement it transcribes—is that in 1899 Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. nakedly claimed that Prochet, Gay & Co. invented gianduia, while recognizing that other companies were contemporaneously staking their own invention claims.

From Rivista Mensile del Club Alpino Italiano, Vol. XIII, January 1894

Who were the other contenders for the title of inventor? This question has avoided the scrutiny of historians for the better part of a century. One likely candidate is Michele Talmone. Talmone continuously operated his factory in Turin from 1850 through the key period of the mid to late 1860s (21). He lived long enough to witness the rise and international dissemination of gianduia (22). At the time he passed the company to his sons, most of them were in their early twenties, old enough to have familiarity with the company’s operations and to build on its success. A full decade before the 1899 Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. statement, Michele Talmone’s heirs had made Talmone the largest chocolate company in Turin, rivaled only by Moriondo & Gariglio (23).

As was the case with Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. near the turn of the century, Talmone claimed to have invented gianduiotti. In 1904, an anonymous author contributed a lengthy article on the history of chocolate to the Almanacco Italiano. In discussing the processing of cacao at the time, the author relies heavily on sources affiliated with Talmone, including Dr. Benedetto Porro (24). In listing some of Talmone’s best known products (beginning with their signature soluble cocoa powder and Cioccolato delle Piramidi), the author describes gianduiotti as “the ancient invention of this house” (25).

Talmone advertisement, 1896

The fact that Talmone’s invention claims were repeated by an almanac author falls well short of bullet-proof historical evidence. Yet it is no weaker than the story that has prevailed for nearly a century, based on one magazine author’s reliance on a contested, non-extant, turn-of-the-century claim by Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. (26).

Thirty-four years after Turin’s 1865 carnival celebrations, there was no apparent consensus on the inventor of gianduia. Yet after Cagliano’s 1932 article appeared in Il Dolce, the claims of Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. have enjoyed nearly eight decades of deference, despite the fact that no new evidence has come to light to corroborate those claims and no alternative hypotheses have been explored. That late-blooming consensus—largely manufactured—cannot bridge the evidentiary gap from the 1860s to the close of the century. As unsatisfying as it is to have to admit this, we have no reliable evidence, at this time, to pinpoint gianduia’s inventor or year of invention.

Notes:

1. Cagliano, A. “Frammenti di Storia del Cacao e del Cioccolato con Particolari Cenni all’Italia e Torino.” Il Dolce: Rivista delle Industrie Italiane del Cioccolato, Biscotti, Caramelle, Confetture ed Affini. Year 7, No. 72, February 1932. Pp. 52-3.

2. As previously mentioned, Michele Prochet joined with Caffarel in 1877. The company went through several changes in ownership and management from the mid-1860s until the time Cagliano wrote his article.

3. Christian Bächstädt-Malan dates Paul Caffarel’s first operations to 1832, the year in which Jean Jacques Watzenborn sold his recently-inherited factory (operated by Bianchini) to Caffarel. See, Per Una Storia dell’Industria Dolciaria Torinese: il Caso Caffarel. Doctoral thesis (Economics and Business), Universitá degli Studi di Torino. 2002. Pp. 68.

4. Cagliano claims that Cailler apprenticed under Caffarel in 1815, before going into business for himself in Switzerland in 1819 (52). This, of course, contradicts the 1826 date Cagliano offers for the origin of Caffarel’s company. Bächstädt-Malan shows that, at the time Cailler opened for business in Switzerland, Paul Caffarel was still living in San Giovanni in Val Pellice (36). Chiapparino cites, and rightfully questions, Wolfgang Mueller’s 1957 work (Seltsame Frucht Kakao: Geschichte des Kakao und der Schokolade) which, in addition to repeating the 1815 Cailler story (for which, Chiapparino notes, there is no corroborating evidence in biographies of Cailler), states that Caffarel was operating outside Porta Susa in Turin in 1802 with two machines made by the Genovese Bozelli and the Piedmontese Doret (L’Industria del Cioccolato in Italia, Germania e Svizzera. Il Molino. Bologna. 1997. P. 248). In addition to the improbability of Paul Caffarel operating an industrial chocolate company at the age of eighteen, this conflicts with the documented facts of the Watzenborns’ ownership of the property and its operation as a tannery at that time.

5. See “Part 9: Did Michele Prochet Invent Gianduia in 1852?” (The answer is, “no.”)

6. Bächstädt-Malan, 94.

7. Further, at the time Prochet joined with Caffarel, the second generation owner (Isidore Caffarel) had already died. The third-generation heir, Alberto Ernesto Caffarel, was fifteen when Prochet took the reins.

8. Bächstädt-Malan, 100.

9. Bächstädt-Malan, 101.

10. Caffarel S.p.A (ed.). Caffarel, 170 Anni: Avanti, Sempre Più Avanti (La Meravigliosa Storia del “Cioccolato d’Autore”). Caffarel S.p.A. 1996. P. 254.

11. The company letterhead on which the circular is printed displays a number of awards received, including a gold medal at the 1906 International Exposition in Milan and what appears to be a gold medal from the 1928 Commercial Exposition in Turin.

12. If the date of the circular could be firmly established, we would know whether the company at the time was under the control of Prochet’s surviving partner Ernesto Malan (through 1916), Malan’s widow Noelie Charbonnier (through 1922), the Balzola-Capietti-Annone investor group (through 1931), or Walter Bächstädt and Paolo Audiberti (from 1931 on). Without knowing who controlled the company at the time of the printing, it is impossible to draw firm conclusions about credibility and motivations.

13. Bächstädt-Malan, Tables 7 and 8.

14. It is worth noting that the 1899 statement does not claim that gianduia was created by Michele Prochet, but by Prochet, Gay & Co. This could reflect humility and generosity towards his partners, if the invention was Prochet’s. Contrariwise, it could mean that gianduia was actually invented by one of Prochet’s partners, both of whom continued to operate after their split with Prochet. If so, Gay, Revel & Co. could also claim to have been the originators, as could (in the same, derivative fashion Caffarel does) their successor in 1906, the Società Anonima Italiana Cioccolato ed Affini (aka SAICA).

15. Bächstädt-Malan, 93-4. In Prochet’s absence, Alberto Ernesto Caffarel, grandson of founder Paul Caffarel, proved the Italian proverb: La prima generazione costruisce, la seconda mantiene, la terza distrugge (i.e., the first generation builds, the second maintains, the third destroys).

16. Ainardi, Mauro Silvio and Paolo Brunati. Le Fabbriche da Cioccolata: Nasscita e Sviluppo di un’Industria Lungo i Canali di Torino. Umberto Allemandi & C., 2008. P. 56.

17. “Seeing how other companies usurp the title of inventors of gianduia, we wish to warn our dear customers that the only creator of this exquisite product, delight of gourmands, was the former firm Prochet, Gay & Co., whose member Michele Prochet continues to operate as a co-owner of the present firm Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co.” (Caffarel 254).

18. Caffarel, 188, 291. The dating of the boxes and cards is not beyond question, as this corporate history, overseen by Carlo Bächstädt-Malan (not to be confused with his nephew Christian Bächstädt-Malan, whose excellent work has been cited elsewhere), is unreliable in many places.

19. Reading that discrepancy in the most charitable light, Prochet was still in retirement in 1895, but had returned to operate the company by the time the 1899 statement was made. Less charitably, but more realistically, if the invention claim had ever been incorporated in Caffarel, Prochet & Co. marketing before Prochet’s 1890 retirement, it is hard to imagine the company would not continue to include it in his absence. And, given the strutting and puffery of late nineteenth century chocolate advertising, it is almost inconceivable that the inventor of a product as popular as gianduiotti would wait over thirty years before asserting that claim in advertising.

20. Caffarel, Prochet & Co. advertisement in Prima Esposizione D’Arte della Città di Venezia, 1895: Catalogo Illustrato. Fratelli Visentini. Venice. 1895. Talmone advertisement in Rivista Mensile del Club Alpino Italiano. Vol. XIII. Turin. January 1894. Moriondo & Gariglio advertisement in Guida di Torino. Roux Frassati & Co. Turin. 1898. P. 63. See also, Prima Esposizione D’Arte della Città di Venezia, 1895: Catalogo Illustrao (page preceding Caffarel, Prochet & Co. ad cited above).

21. There is no question about whether Talmone was in business in 1865, whereas the earliest record of activity for Prochet, Gay & Co. is in 1866.

22. Michele Talmone died in Turin on September 11, 1882. The dissemination of gianduia will be discussed in more detail in a subsequent report.

23. Annali di Statistica: Statistica Industriale, Fascicolo XVII, Notizie sulle Condizioni Industriali della Provincia di Torino. Ministero di Agricoltura, Industria e Commercio. Direzione Generale della Statistica. Tipografia Eredi Botta. Rome. 1889. P. 72.

24. Referenced only as Professor Porro in the article, this was Dr. Benedetto Porro of the Scuola Municipale di Chimica Cavour. Talmone retained the chemist as an expert witness in responding to allegations of the use of adulterants in their products in the mid-1890s. See, Gianolio, Bartolomeo and Enrico Cavaglià. Memoriale a Difesa nell’Interesse dei Signori Talmone (Enrico, Amedeo, Alberto, Gustavo e Michele), Appellanti da Sentenza 27 Giugno 1894 del Tribunale Penale di Torino. Tipografia Baravalle e Falconieri. Turin. 1895.

25. “Diva Caraca: Curiosità Storiche Aneddoti e Varietà sul Cacao; Sue Virtù Prodigiose,” in Almanacco Italiano: Piccola Enciclopedia Popolare della Vita Pratica, e Annuario Diplomatico, Amministrativo, e Statistico (Year 10, 1905). R. Bemporad & Figlio. Florence. 1904. (P. 495.) A similar, but less unambiguous claim, appeared in the 1903 version of the same almanac (p. 406).

26. Considering the marketing mileage that Caffarel has gained from its uncontested invention claims for eighty years, Venchi (the present-day corporate descendent of Talmone) would do well to invest in some research to see whether Talmone’s invention claims preceded those of Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. and whether there is any corroborating evidence to support those claims.