From March through October of 1847, King Carlo Alberto issued a series of edicts expanding freedom of the press, including the right of publications to comment on matters of public administration (1). Within months, Turin was flooded with new newspapers with decidedly liberal and revolutionary editorial stances.

One such paper, Il Risorgimento, edited by Camillo Cavour, strongly advocated for a constitution (2). In March of 1848, Carlo Alberto proclaimed the Statuto, a constitution informed by that of the French, which formally granted broad freedom of the press. (As previously noted, it was also in this time of reform that the Waldenses were accorded civil liberties.) Inspired by French and English satirical papers that circulated among Turin’s educated class (including London’s Punch, which took its name from the English puppet descended from the Neapolitan Pulcinella), the satirical press in Piedmont was born in 1848.

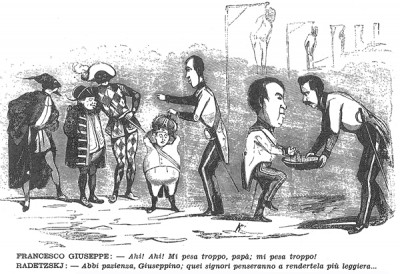

On November 2, 1848, a Turinese attorney, Nicolò Vineis, and cartoonist, Icilio Pedrone, launched Il Fischietto (3). One month later, the paper gave Gianduia his first appearance in a political cartoon (pictured to the left). Pedrone drew Gianduia standing beside Pantalone and Arlecchino—the commedia dell’arte characters representing Piedmont, Veneto, and Lombardy, respectively. The eighteen-year-old Franz Joseph I, succeeding his uncle to the Austrian throne on December 2, is infantilized by the artist, complaining of the weight of the crown to his “papa,” Austrian Field Marshal Josef Radetsky. Radetsky urges “little Joseph” to be patient, pointing to the three Italian masks who are already planning to lighten the king’s load (4).

On November 2, 1848, a Turinese attorney, Nicolò Vineis, and cartoonist, Icilio Pedrone, launched Il Fischietto (3). One month later, the paper gave Gianduia his first appearance in a political cartoon (pictured to the left). Pedrone drew Gianduia standing beside Pantalone and Arlecchino—the commedia dell’arte characters representing Piedmont, Veneto, and Lombardy, respectively. The eighteen-year-old Franz Joseph I, succeeding his uncle to the Austrian throne on December 2, is infantilized by the artist, complaining of the weight of the crown to his “papa,” Austrian Field Marshal Josef Radetsky. Radetsky urges “little Joseph” to be patient, pointing to the three Italian masks who are already planning to lighten the king’s load (4).

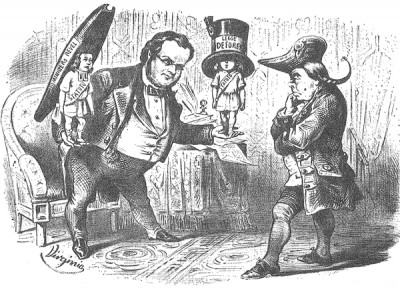

Virginio (Fischietto, No. 48, April 22, 1858)

While Pedrone’s early drawing used Gianduia simply as a symbol of Piedmont, he and other notable cartoonists, such as Francesco Redenti, Ippolito Virginio, and Casimiro Teja, quickly grew more sophisticated in their use of the character (5). Piedmont’s driving role in the unification movement made Gianduia a useful symbol of the Risorgimento itself. Sometimes Gianduia carped at Cavour; sometimes he cheered him on. (Redenti even depicted Camillo Cavour as Gianduia.)

Redenti (Fishietto, No. 155, December 27, 1859)

Gianduia voiced complaints and encouragement about Piedmont’s involvement in the Crimean War and the War of 1859. While Gianduia was invariably the protagonist in Piedmontese political cartoons, reactionaries and satirical illustrators from other regions often portrayed the character as an antagonist. Cartoonists used Gianduia to comment on every major political figure or event of the 1850s, providing a constant drumbeat for independence and unification (5).

Mata (Lampione (Florence), No. 1, March 1, 1862)

Virginio (Fischietto, No. 21, February 18, 1858)

By the early 1860s, the image of Gianduia had become as powerful and versatile for propaganda or polemic as Uncle Sam or John Bull, in their respective countries. The identification was so complete that Cavour himself occasionally referred to Piedmont simply as Gianduia in correspondence (6). Describing the indispensability of Piedmontese support in a Parliamentary struggle in 1857, Cavour wrote to the Marquis D’Azeglio, “Without Gianduia, we would’ve been fried” (7).

Notes:

1. Picca, Cesario. Senza Bavaglio: L’Evoluzione del concetto di Libertà di Stampa. Edizioni Pendragon. Bologna. 2005. Pp. 20-1. These advances were consolidated with the proclamation of the Statuto the following year.

2. Chiala, Luigi (ed.). Lettere Edite ed Inedite di Camillo Cavour (Volume I). Roux e Favale. Turin. 1884. P. cxii.

3. Manno, Antonio and Vincenzo Promis. Bibliografia Storica degli Stati della Monarchia di Savoia (Vol. I). Fratelli Bocca Librai di S.M. Turin. 1884. P. 237.

4. Il Fischietto. No. 20. December 16, 1848.

5. Gianeri, Enrico. Gianduja nella Storia, nella Satira. Famija Turineisa. Turin. 1962. Pp. 27-52. Gianeri’s book is the definitive history of political and artistic uses of Gianduia in the nineteenth century.

6. “Common sense always helps Gianduia in difficult moments.” Massari, Giuseppe. Il Conte di Cavour: Ricordi Biografici. Tipografia Eredi Botta. Turin. 1875. P. 208.

7. Chiala (Vol. II), 505.