In the early decades of the nineteenth century, before the Waldenses could safely descend from their valleys, chocolate production in Turin was dominated by immigrants from Canton Ticino in Italian Switzerland—particularly from alpine villages in the Blenio valley. For over a century, harsh winters in the Alps, coupled with a predominately agricultural economy, encouraged seasonal migration for work at lower elevations, including in the population centers of northern Italy (1). Bleniese migrants often took work in the cities as peddlers, chestnut roasters, and, most importantly, cacao grinders.

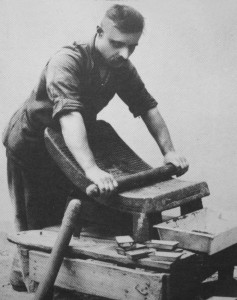

Bleniese cacao grinder (from L'Oro Bruno; Pusterla Cambin and Foni, 2007)

Working with cacao developed a marketable skill set that permitted many Bleniese laborers to remain in the cities year-round. As chocolate consumption started to spread beyond the upper class, many individual chocolate makers left the employ of wealthy families and began fulfilling orders for hotels and monasteries, with the more entrepreneurial opening chocolate shops. Business growth allowed more family and extended relations to be brought from Ticino, forming interlocked family networks that vertically integrated the chocolate business in Turin—distribution of raw materials, production of chocolate, as well as wholesale and retail sales (2).

Nicaraguan women grinding chocolate (from Cocoa and Chocolate; Arthur Knapp, 1920)

For the first two decades of the nineteenth century, the prevailing methods of chocolate making in Turin remained highly laborious, with grinding done by hand using a prea—a concave stone table very similar to the Aztec metate (3). This labor-intensiveness provided simple opportunity for early Bleniese immigrants, but became a significant competitive advantage for them as their connections to Ticino provided a ready supply of labor to fuel growth. Listings of chocolate makers and merchants in Turin from this period are strewn with names of families from Canton Ticino: the Barreras, Emas, Giambones, Bianchis, Giulianos, and Giroldis (4). Yet the ingenuity of one Bleniese chocolate-maker changed the game decisively.

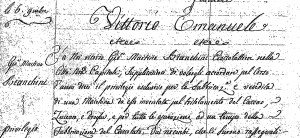

Bianchini's patent (from Per Una Storia dell'Industria Dolciaria Torinese; Christian Bächstädt-Malan, 2002)

Giovanni Martino Bianchini was born in Campo, Canton Ticino, in 1778. By his early forties, he found his way into the chocolate industry of Turin. On July 17, 1819, Bianchini petitioned King Carlo Felice for a patent for “a machine [he] invented for the trituration of cacao, sugar, and drugs, and for all of the operations in connection with the manufacture of chocolate” (5).

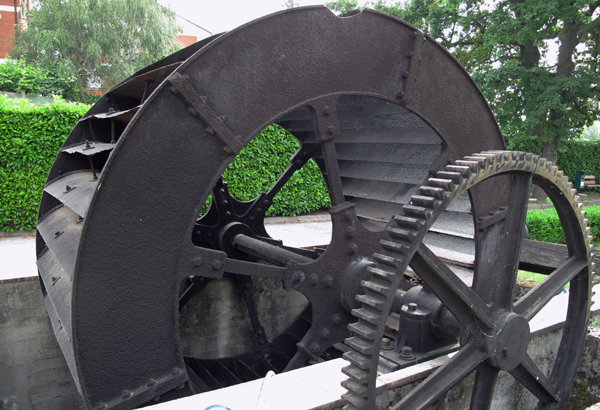

Bauermeister mélangeur; Amano Artisan Chocolate (Orem, Utah)

While the patent models and the actual device no longer exist, contemporary accounts describe a complex water wheel-powered device that served a number of purposes, including cleaning and sorting cacao (possibly with a cylinder sieve), roasting (probably with a rotating drum), winnowing and sorting nibs, grinding (probably in a manner similar to French mélangeurs), and refining (probably also with granite wheels or cylinders) (6).

Though Bianchini’s invention shared features of machines then in use in other countries, it was the first step towards industrialization of chocolate in Piedmont (7). Substituting hydropower for manpower enabled more and faster production, greater uniformity and refinement in texture, and lower costs. Bianchini had the idea, the machine, and—on November 26, 1819—the royal patents (8). All he lacked was the water.

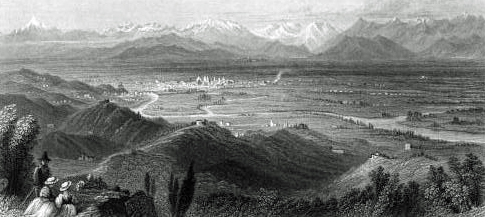

Turin and plains of Piedmont (from The Waldenses; Beattie, 1838)

Near the foot of the Cottian and Graian Alps, Turin sits in a plain delineated by three rivers—the Stura di Lanzo, Sangone, and Po—and is bisected by a fourth, the Dora Riparia. The rivers provided practical and strategic advantages in the city’s early history, but became even more instrumental to its economic development in the Middle Ages with the construction of bealere.

Bealere were artificial watercourses fed by the rivers. Generally at ground level and with earthen banks, bealere often ran beside rural roads or along agricultural field boundaries. Canalizing river water rendered more land arable, supporting greater population in the city. Bealere also powered proto-industrial mills—grain mills, textile mills, tanneries, forges, paper mills, etc. The nineteenth century saw public works projects to enlarge and fortify Turin’s bealere, as well as to construct modern canals (9).

At the close of the eighteenth century, Napoleon’s policy of religious tolerance in northern Italy coaxed some Waldensian families from their valley refuges. One such family was that of Jacques Philippe Watzenborn (formerly Landeau) who, along with his wife Madeleine and four children, left his home in the Waldensian community of San Giovanni (in Val Pellice) to settle in the Valdocco quarter of Turin (10).

In 1799, shortly before Napoleon reaffirmed control over Piedmont in the Battle of Marengo, Watzenborn purchased a piece of land along the Canal of Turin, with a cottage, garden, and orchard. A tanner, by trade, Watzenborn converted the property into a tannery. In 1805, he installed a waterwheel to turn a liming drum and to mill acorns to produce tannic acid. Watzenborn died a few years later, leaving the property to his widow Madeleine and children. Madeleine Watzenborn continued to operate the tannery for over a decade, applying for and obtaining a concession from the City of Turin for a new waterwheel in 1817 (pictured at the top of this article). The concession stipulated that the waterwheel be limited to specifically permitted, tanning-related uses (11).

Turin and the Dora Riparia (from The Waldenses; Beattie, 1838)

In 1820, the widow Watzenborn and her son Jean Jacques wrote to the Mayor of Turin describing changing circumstances in the tanning business that prompted her to request a modification in permitted use for the waterwheel. She went on to describe a local chocolate manufacturer, Giovanni Martino Bianchini, and his patented invention for using waterpower to make chocolate. The city granted the request (12).

Less than one year after the revised concession, Giovanni Martino Bianchini had installed and was operating his invention in the building housing the former tannery. When the concession expired in 1828 and the city demanded removal of the waterwheel, Madeleine Watzenborn agreed to pay higher license fees to keep the chocolate factory in operation.

Within three years of renewing the concession, the widow Watzenborn died. On May 1, 1832, her son and heir Jean Jacques executed a bill of sale transferring ownership of the land and factory to a fellow Waldensian from San Giovanni, Paul Caffarel (13).

Paul Caffarel (from Caffarel, 170 Anni; 1996)

Upon taking ownership, Caffarel—under the Italianized name Paolo Caffarelli—adopted a more hands-on approach with the factory, working alongside Giovanni Martino Bianchini until the latter’s death in 1837 (14). Caffarelli blamed the patented machine for a lingering sadness that he felt contributed to Bianchini’s illness and death, noting that the inventor made constant exertions and expenditures to modify and improve his machine, without ever realizing the profits to which he felt entitled (15).

For the chocolate industry in Turin, Caffarel’s purchase of the Watzenborn factory and Bianchini’s death symbolize the passing of the baton from artisanal Bleniese immigrants to the early industrialism of the Waldenses. While the names Watzenborn and Bianchini are lost to history, Caffarel remains familiar to chocolate cognoscenti to this day.

Notes:

1. Chiapparino, Francesco. “Tecnologie, Capitali e Mercati: I Rapporti Italo-Svizzeri nel Settore del Cioccolato,” in Il Cioccolato: Industria, Mercato e Società in Italia e Svizzera (XVIII-XX Sec.). FrancoAngeli. Milan. 2007. P. 173.

2. Lorenzetti, Luigi. “Emigrazione, Imprenditorialità e Rischi: I Cioccolatai Bleniesi (XVIII-XIX Secc.),” in Il Cioccolato: Industria, Mercato e Società in Italia e Svizzera (XVIII-XX Sec.). FrancoAngeli. Milan. 2007. P. 44.

3. Chiapparino [2007], 173.

4. Pusterla Cambin, Patrizia and Valentina Foni. L’Oro Bruno: Cioccolato e Cioccolatieri delle Terre Ticinesi. Museo storico etnografico di Blenio. 2007. Pp. 50-70. See also, Ainardi, Mauro Silvio and Paolo Brunati. Le Fabbriche da Cioccolata: Nasscita e Sviluppo di un’Industria Lungo i Canali di Torino. Umberto Allemandi & C., 2008. Pp. 50-1.

5. Ainardi, 45.

6. Ainardi, 46.

7. The functional description of the device hews closely to established mechanical processes used in industrial chocolate making outside of Italy at the time, raising some doubt about the “independence” of Bianchi’s invention.

8. Ainardi, 47.

9. Ainardi, 15-17.

10. At the time, San Giovanni was a separate municipality from Luserna, just across the Pellice torrent. In 1872, the two were combined into the present-day Luserna San Giovanni.

11. Ainardi, 18-19.

12. Ainardi, 18-19.

13. Bächstädt-Malan Camusso, Christian. Per Una Storia dell’Industria Dolciaria Torinese: il Caso Caffarel. Doctoral thesis (Economics and Business), Universitá degli Studi di Torino. 2002. Pp. 69-70. Less than a month later, Jean Jacques Watzenborn married Paul Caffarel’s daughter, Marie Pauline Caffarel.

14. Given the persecution Waldenses still faced outside their native valleys in Piedmont, most who moved into the plains and Turin Italianized their surnames to maintain a low profile. For example, Madeleine and Jean Jacques Watzenborn were known in Turin as Maddalena and Giacomo Giovanni Watzembourn.

15. Ainardi, 49.