The Napoleonic myth does not hold water (Part 4). The thirteen-year-old Michele Prochet did not invent gianduia in 1852 (Part 9). The best evidence for Prochet, Gay & Co.’s invention in 1865 is an unsubstantiated statement by Prochet’s company over thirty years after the fact, which openly acknowledges that the claim was contested (Part 13). The tales of gianduia’s naming first appeared over sixty years after the fact and are riddled with internal and external inconsistencies (Part 14). So where does that leave us?

Unfortunately, at present, we cannot pinpoint gianduia’s inventor or date of invention. Recognizing that, however, is the first step towards breaking loose from nearly a century-long feedback loop of charming, but historically unsound folklore and commercial propaganda. Finding real answers will require digging into nineteenth century publications and manuscripts.

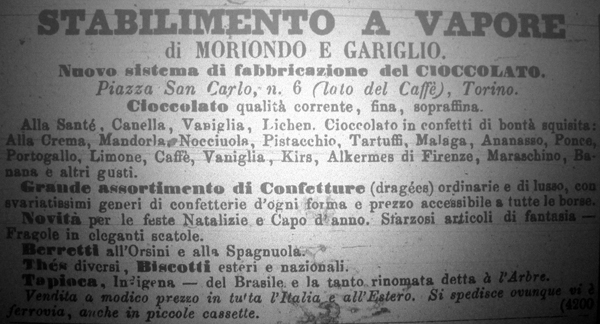

Gazzetta Piemontese, January 2, 1869.

While carnival season in the late 1860s seems like a credible time for the emergence of gianduia, given the reinvigorated celebrations under the direction of the Society of Gianduia, the natural seasonality of gianduia, and the maturing chocolate industry in Turin, sources from the period offer no persuasive evidence of the existence of gianduiotti. The extensive coverage of carnival in the newspapers of the day might raise hopes of finding descriptions of or advertisements for gianduiotti. However, the papers provide little evidence (1).

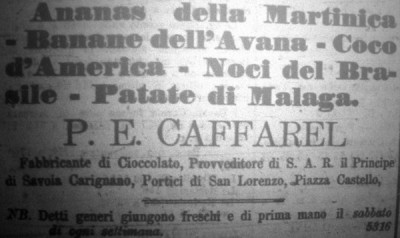

Caffarel publicity card, 1870.

Neither editorial content nor bulletins from the Society of Gianduia mention anything resembling gianduiotti. Advertisements from chocolate makers and chocolatiers are few and unhelpful. A January 1869 advertisement from P.E. Caffarel, “Fabbricante di Cioccolato,” does not even tout chocolate, but rather pineapples from Martinique, bananas from Havana, Brazil nuts, and sweet potatoes from Malaga (2). 1869 advertisements for Moriondo & Gariglio make passing mention of cioccolato alla nocciola (3). While tantalizing, these references are buried in a broad laundry list of chocolate confections flavored with almonds, pistachio, sweet potato, pineapple, banana, Alchermes, Kirsch, coffee, vanilla, lemon, et al., suggesting that it was a bonbon of some sort, rather than a gianduiotto. An 1870 publicity card from Caffarel mentions nougat and hazelnut pralines, but no gianduia (4).

Until further research reveals contemporary evidence of gianduia in the 1860s, we must examine the subsequent pattern of diffusion. Traditionally, it has been believed that gianduiotti began as a thoroughly local product, but quickly spread throughout Italy and beyond. This successful diffusion would be remarkable, considering the relative insignificance of Turinese chocolate makers on the world stage.

From the 1860s to 1880s, Turinese chocolate companies remained proto-industrial enterprises of relatively modest scale. In 1889, only five mechanized chocolate factories operated in Turin: Talmone, Moriondo & Gariglio, Gay & Revel, Giuliano, and Caffarel, Prochet & Co. All together, the five companies employed only 102 workers (over three-fifths of them in the Waldensian-owned shops) (5). For perspective, the Swiss chocolate maker Sprüngli at the same time had over five times the number of employees as all of the chocolate factories in Turin combined (6). Suchard, even larger and already multinational, was at the time building a model village, named Cité Suchard, for the workers of its main factory in Neuchâtel and was acquiring a 100,000-tree cacao estate in the Dominican Republic (which fell far short of supplying the company’s raw material requirements) (7).

The spread of gianduia in the international market could not, therefore, result from the size or productivity of Turinese makers. It would be a testament to their ingenuity, production quality, and, perhaps, to their marketing skill.

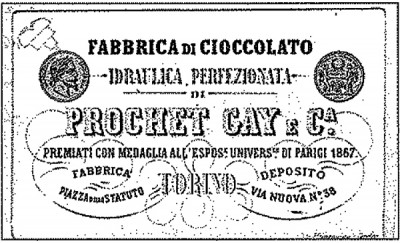

Prochet, Gay & Co. publicity card, 1870.

National and universal expositions may have served as the primary vector for international awareness of gianduia. Prochet, Gay & Co. participated in the 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris, two years after the company allegedly invented gianduiotti (8). The jury awarded the Waldensian newcomers a medal for quality (9). The obverse of the Ponscarme-designed medal, as depicted in a Prochet, Gay & Co. publicity card from 1870, reveals that it was a bronze (10). The fact that the medal appeared prominently on the publicity card offers a clue to the purpose of Prochet’s appearance at the Exposition and that of other Turinese makers in subsequent expos and fairs. The Waldensians (and, later, non-Waldensians such as Moriondo & Gariglio) did not participate solely out of a desire to penetrate foreign markets, but to obtain international recognition for purposes of domestic marketing.

When Prochet, Gay & Co. attended the next world exposition in Vienna in 1873, Moriondo & Gariglio also appeared, receiving a medal of merit (11). More notably, however, G. Phillips Bevan, reporting for the Royal Commission on the Vienna exposition, observes that the Swiss giant “Cailler & Cie., of Vevay, exhibited hazel-nut chocolate” (12). Bevan also notes that “H. Goll, [of] Lausanne, showed chocolates, for which he claimed absolute purity, together with some new confectionery, such as pine kernel and almond kernel chocolate” (13). He is silent on the subject of Italian chocolate (14).

If gianduia was invented in Turin in the mid-1860s and taken by Prochet, Gay & Co. to the 1867 Paris exposition, foreign chocolate makers and confectioners would naturally take note and possibly imitate. Swiss experimentation with nut chocolates in 1873 would be consistent with that. Yet, the present lack of contemporary evidence of gianduia’s existence in Turin during the 1860s compels us hypothesize—however blasphemously—that the Swiss may have independently invented chocolat à la noisette or even been a source of inspiration for Turinese gianduia and gianduiotti (15). Resolving this critical uncertainty will require further research of period documents (16).

When the Exposition Universelle returned to Paris in 1878, Gay & Revel (Michele Prochet’s former partners) and Moriondo & Gariglio received silver medals (17). Moriondo & Gariglio received a gold medal in the Paris Expo of 1889, as well as in several regional and national expositions, from Cape Town to Amsterdam (18).

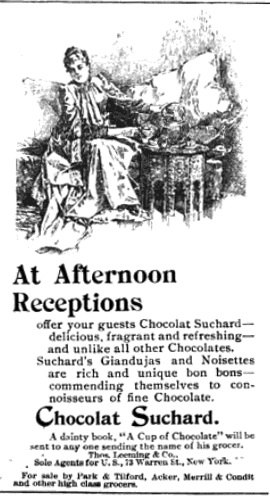

Suchard ad for giandujas. Life, November 15, 1894.

Apart from world expositions, gianduia continued to spread outside of Italy through the latter decades of the century. In 1885, a French Jesuit returning from a mission to Armenia saw sacks of hazelnuts loaded into the ship, destined for chocolate makers in Marseille who found it more economical to make chocolat à la noisette (19). By 1889, the Association of Swiss Analytical Chemists recognized chocolat à la noisette as an established form of chocolate product (20). In the 1890s, advertisements for Swiss-made gianduia (using the Italian term) appeared in the United States in Life magazine and the San Francisco Call (21).

Recognition and acceptance of gianduia continued across Italy, as well. Gianduia soon began appearing in Italian lexicons and dictionaries. Fanfani and Frizzi’s 1883 Nuovo Vocabolario Metodico della Lingua Italiana includes a lively description of gianduia as “small balls or morsels of superfine, tender chocolate, of irregular form, which are sold wrapped in silver paper….and are now commonly consumed in all of Italy by people of a certain affluence” (22). Policarpo Petrocchi’s 1892 dictionary includes “Cioccolatini Gianduia” (i.e., little chocolates of Gianduia) under the general entry for chocolate; but in an expanded, two-volume dictionary two years later, Petrocchi lists “Gianduiotti” as a synonym for cioccolatini Gianduia under the general entry for Gianduia (23). Before long, gianduia also began appearing in Italian books on food and cooking (24).

At the turn of the century, foreign travel and guidebooks specially noted and recommended gianduiotti. Henry Lyonnet devotes an entire chapter in his 1897 book of travel essays to the history of Gianduia (the mask) in Piedmont, describing the confections bearing the name as “those delicious bonbons of chocolat à la noisette that are enveloped in small paper wrappers of gold and silver, and that bring joy to children” (25). (Lyonnet opens the chapter aptly: “Si vous ne connaissez pas Gianduja, vous ne connaissez ni Turin, ni aucune ville du Piémont.“) In The Gourmet’s Guide to Europe (1903), Nathaniel Newnham-Davis recommends gianduiotti as a fitting way to end a meal in Turin (26). Baedeker’s 1906 Handbook for Travellers states that “The chocolate made in Turin (Gianduia) is noted” (27).

While it seems likely that the fusion of chocolate and hazelnuts originated in Piedmont, Piedmont unquestionably became the world capital of gianduia. By the early twentieth century, it had become a signature of Turinese gastronomy, as well as a permanent fixture in European confectionery.

1. This is based on a review of the carnival season issues of Gazzetta del Popolo (from 1865 through 1873) and Gazzetta Piemontese (from 1867 through 1873). Coverage becomes more sporadic in 1872 with the reorganization of carnival under a new Society of Gianduia (with bulletins issued by Gianduia II). Given the importance of the Christmas season to chocolate makers and confectioners, review of December issues is also warranted. (If someone wants to send me a complete microfilm collection of both papers from 1860 to the close of the century, I’m game.)

2. Gazzetta Piemontese, January 2, 1869.

3. Gazzetta del Popolo, January 1 & 3, 1869.

4. Even so, this does show that chocolate and hazelnuts were being paired at the time. Though sample size is a problem, the peculiar silence about gianduiotti in chocolate makers’ advertising seems to persist for decades, until the 1890s, when all of the major players are aggressively advertising gianduiotti. Increased advertising at the turn of the century could also be a result of improving economic conditions at the time. “The period from the 1890s until the First World War has often been characterized as one of improvement for both the economic and physiological health of the nation.” (Hesltosky, Ruth. Garlic & Oil: Food and Politics in Italy. Berg Publishers. New York. 2004. P. 33.)

5. Annali di Statistica: Statistica Industriale, Fascicolo XVII, Notizie sulle Condizioni Industriali della Provincia di Torino. Ministero di Agricoltura, Industria e Commercio. Direzione Generale della Statistica. Tipografia Eredi Botta. Rome. 1889. P. 72.

6. 150 Years of Delight: Chocoladefabriken Lindt & Sprüngli AG, 1845-1995. Chocoladefabriken Lindt & Sprüngli. Kilchberg. 1995. P. 44.

7. Dawson, William Harbutt. Social Switzerland: Studies of Present-day Social Movements and Legislation in the Swiss Republic. Chapman & Hall, Ld. London. 1897. P. 90. Clarence-Smith, William Gervase. Cocoa and Chocolate, 1765-1914. Routledge, 2000. P. 105.

8. The Expo began in April. If the 1899 Succ. Caffarel Prochet & Co. statement is accurate, the 1867 name change—of givo to gianduia—would have already occurred before Prochet, Gay & Co’s arrival in Paris.

9. Ainardi, Mauro Silvio and Paolo Brunati. Le Fabbriche da Cioccolata: Nasscita e Sviluppo di un’Industria Lungo i Canali di Torino. Umberto Allemandi & C., 2008. Pp. 80-1.

10. Caffarel, Prochet & Co.’s late-nineteenth century claims to have been present at the 1867 Expo appear to be derived from Prochet, Gay & Co.’s participation. However, Paolo Ernesto Caffarel was present in Paris in late 1867, as evidenced by a diploma from the Académie Nationale, Agricole, Manufacturière et Commerciale. Caffarel S.p.A (ed.). Caffarel, 170 Anni: Avanti, Sempre Più Avanti (La Meravigliosa Storia del “Cioccolato d’Autore”). Caffarel S.p.A. 1996. Pp. 44-5.

11. Ainardi, 88. Whether Moriondo & Gariglio or Prochet, Gay & Co. brought gianduia to the exposition is unknown.

12. Reports on the Vienna Universal Exhibition of 1873, Part IV; Presented to Both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty. George E. Eyre and William Spottiswoode, Printers to the Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty. London. 1874. Pp. 213-4.

13. Reports on the Vienna Universal Exhibition of 1873, Part IV, 213.

14. Reports on the Vienna Universal Exhibition of 1873, Part IV, 210-2. It should also be noted that Bevan devotes more words to the Italian exhibitors than the Swiss.

15. Also, we cannot simply assume that Swiss experimentation with hazelnut chocolate began in 1873. If additional research pushes that date back, it will further narrow the window for proof of Turinese invention.

16. Though I believe gianduia was invented in Turin in the mid to late 1860s, the loosely-held conviction is based on little more than hunch, recognition that important sources remain to be scoured, and affection for the Waldenses and Piedmontese who made gianduia one of the most sublime expressions of the art of chocolate.

17. Anfosso, Carlo. “Torino Industriale,” in Torino (Bersezio, Vittorio, et al.). Roux e Favale. Turin. 1880. P. 801. The prior year, Michele Prochet had left Prochet, Gay & Co., then one of the largest makers in Turin. Anonymous. “The Industries of Turin,” Journal of the Society of Arts (No. 1,296. Vol. 25, p. 974). George Bell & Sons, September 21, 1877.

18. Ainardi, 88.

19. Annales de la Propagation de la Foi, vol. 57. Lyon. 1885. P. 168.

20. Zeitschrift für Nahrungsmittel-Untersuchung und Hygiene. Bayer & Comp. Vienna. 1889. P. 104.

21. Life, Nov. 15, 1894. San Francisco Call, Dec. 18, 1899, p. 3.

22. Fanfani, Pietro & Giuseppe Frizzi. Nuovo Vocabolario Metodico della Lingua Italiana, P. I. Libreria d’Educazione e d’Istruzione. Milan. 1883. P. 841. The specification of “superfine” set the product above the lower quality categories established by manufacturers (e.g., fina and corrente) for chocolates containing lower percentages of cacao solids and, in many cases, what we would now consider adulterants.

23. Petrocchi, Policarpo. Nòvo Dizionàrio Scolàstico della Lingua Italiana. Fratèlli Trèves, Editori. Milan. 1892. P. 204. Petrocchi, Policarpo. Nòvo Dizionàrio Universale della Lingua Italiana, Vol. I. Fratèlli Trèves, Editori. Milan. 1894. P. 1038.

24. Cougnet, Alberto. Il Ventre dei Popoli: Saggi di Cucine Etniche e Nazionali. Fratelli Bocca, Editori. Turin. 1905. P. 480. Ciocca, Giuseppe. Il Pasticciere e Confettiere Moderno. Ulrico Hoepli. Milan. 1907. P. lv.

25. Lyonnet, Henry. Excursions, Historiques et Littéraires. Paul Ollendorff, Éditeur. Paris. 1897. P. 43.

26. Newnham-Davis, Lieut.-Col. Nathaniel and Algernon Bastard. The Gourmet’s Guide to Europe. Grant Richards. London. 1903. P. 160. This holds today, as many Michelin-starred restaurants in Piedmont include a house-made gianduiotto among the mignardises.

27. Baedeker, Karl. Italy: Handbook for Travellers. First Part: Northern Italy, including Leghorn, Florence, Ravenna, and Routes through Switzerland and Austria. Charles Scribner’s Sons. New York. 1906. P. 28.