Having introduced the Waldensian dramatis personæ, we move on to the next oft-cited date for the origin of gianduia: 1852.

The basic narrative is that, in 1852, Michele Prochet (pictured above), one of the Waldensian principles of Prochet, Gay & Co., stumbled upon the idea of grinding hazelnuts with chocolate. Some common variations on the story have a (usually unspecified) Caffarel either replacing or, less ungenerously, collaborating with Prochet (1). Some qualify that Prochet’s invention was of simple gianduia paste and not gianduiotti (2). Some transplant the scarcity/necessity memes from the Napoleonic narrative into mid-century Turin (3). Though the story is common in both English and Italian publications, none provide any contemporaneous evidence for the 1852 invention of gianduia, whether by Prochet or anyone else.

The earliest extant source for the story (and its probable origin) is an article by A. Cagliano in the February 1932 issue of the trade magazine Il Dolce (4). Cagliano writes that “…the first company that had the idea of combining [roasted] hazelnuts with chocolate was Prochet, Gay & Co.” and dates the invention in 1852 (5). Cagliano later repeats that “The true inventor [of gianduia paste] was Mr. Michele Prochet” (6).

The earliest extant source for the story (and its probable origin) is an article by A. Cagliano in the February 1932 issue of the trade magazine Il Dolce (4). Cagliano writes that “…the first company that had the idea of combining [roasted] hazelnuts with chocolate was Prochet, Gay & Co.” and dates the invention in 1852 (5). Cagliano later repeats that “The true inventor [of gianduia paste] was Mr. Michele Prochet” (6).

The eighty-year gap between this supposed invention by Prochet and the first known written record of it raises some doubt about the reliability of the information. Those doubts are exacerbated by errors and anachronisms in the account, the key one being the 1852 date (7). While Cagliano has Prochet, Gay & Co. operating in Turin in 1852, the earliest record of Prochet’s professional activity in the city is in 1866 (8).

There’s no record of Michele Prochet Italianizing his name, as had most of the key mid-century Waldensian chocolate-makers (e.g., Landeau/Watzemborn, Caffarel/Caffarelli, Talmon/Talmone). This would be consistent with his arrival on the scene long enough after the 1848 Statuto and letters-patent for greater religious tolerance to have blossomed in Turin, making the 1866 date more plausible. (Similarly, Prochet’s partners, Gay and Revel, did not change their distinctively Waldensian surnames.)

Grave marker for Michele Prochet (Luserna San Giovanni)

Most damaging to Cagliano’s chronology, Michele Prochet was born in San Giovanni on March 25, 1839. If Cagliano’s date were correct, it would mean Prochet was pioneering industrial chocolate-making in Turin and inventing gianduia at the tender age of thirteen (9).

The myth that Michele Prochet invented gianduia in 1852 should be abandoned (10).

Notes:

(1) Meldolesi, Alessandra. L’Italia del Cioccolato. Touring Editore. Milan. 2004. Pp. 96-7. See also, Mantovano, Laura. I Maestri del Cioccolato. G.R.H. S.p.A. 2004 P. 200. See also, Coady, Chantal. The Chocolate Companion: A Connoisseur’s Guide. Running Press. 2006. P. 49.

(2) Ainardi, Mauro Silvio and Paolo Brunati. Le Fabbriche da Cioccolata: Nasscita e Sviluppo di un’Industria Lungo i Canali di Torino. Umberto Allemandi & C., 2008. P. 108.

(3) Blythman, Joanna. “Chocolatissimo!” The Guardian, March 23, 2002. See also, Segan, Francine. “La Dolce Vita: Italian Chocolate.” Tribune Media Syndicates. 2008.

(4) Cagliano, A. “Frammenti di Storia del Cacao e del Cioccolato con Particolari Cenni all’Italia e Torino.” Il Dolce: Rivista delle Industrie Italiane del Cioccolato, Biscotti, Caramelle, Confetture ed Affini. Year 7, No. 72, February 1932. Pp. 48-53. This article was part of a serialization of an unpublished manuscript by Cagliano, with articles appearing in Il Dolce over the course of several years.

(5) Cagliano argues that Prochet’s originality was in grinding roasted hazelnuts with cacao, after setting forth a dubious claim that chocolate had previously been combined with raw hazelnuts in the Americas. In support of this, Cagliano cites Tractatus Novi de Potu Caphé, de Chinensium Thè, et de Chocolata (1685)—a Latin translation of a French text by the pseudonymous Philippe Sylvestre Dufour, aka Jacob Spon (Traitez Nouveaux & Curieux du Café, du Thé, et du Chocolate), compiling, editing, and translating from, among others, seventeenth century Spanish works by Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma (Curioso Tratado de la Naturaleza y Calidad del Chocolate) and Bartolomeo Marradon (Diálogo del Uso del Tavaco, los Daños que Causa, y del Chocolate e Otras Bebidas).

(5) Cagliano argues that Prochet’s originality was in grinding roasted hazelnuts with cacao, after setting forth a dubious claim that chocolate had previously been combined with raw hazelnuts in the Americas. In support of this, Cagliano cites Tractatus Novi de Potu Caphé, de Chinensium Thè, et de Chocolata (1685)—a Latin translation of a French text by the pseudonymous Philippe Sylvestre Dufour, aka Jacob Spon (Traitez Nouveaux & Curieux du Café, du Thé, et du Chocolate), compiling, editing, and translating from, among others, seventeenth century Spanish works by Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma (Curioso Tratado de la Naturaleza y Calidad del Chocolate) and Bartolomeo Marradon (Diálogo del Uso del Tavaco, los Daños que Causa, y del Chocolate e Otras Bebidas).

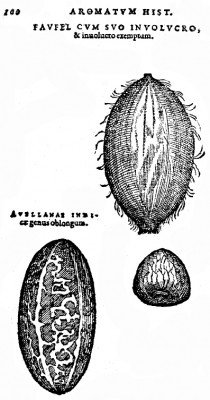

"Indian Hazelnuts"/Betel Nuts (from Aromatum; Cristóvão da Costa, 1596)

While Colmenero (not Marradon, pace Cagliano) does provide a chocolate recipe with the addition of “almonds” and “hazelnuts,” according to René Moreau’s annotations that were included in the Latin translation on which Cagliano relies (pp. 158-9) and in the French by Dufour/Spon (pp. 288-9), those terms referred to New World nuts, rather than their European counterparts. In an effort to identify Colmenero’s avellanas, Moreau quotes the Portuguese natural historian Cristóvão da Costa for a description of what Moreau mistranslates as “noisettes des Indes Occidentales.” This also misses the mark, since da Costa’s auellanae Indicae were betel nuts—seeds of the areca palm—from the East (not West) Indies. The 1593 Latin original of da Costa’s Aromatum includes an illustration of these “Indian hazelnuts” which cannot possibly be mistaken for European hazelnuts. Betel nuts were, of course, as foreign as European hazelnuts to the Americas.

Whether Colmenero’s avellanas were Brazil nuts, cashews, or some other New World nut, seed, legume, or drupe, they were not European hazelnuts (Corylus avellana), which did not—and, indeed, could not—grow in cacao-producing regions of the Americas. While Europeans, particularly the Spanish, did come to grind cacao with Old World almonds (even in Mexico, after their introduction there—a practice which continues today), a suitable ratio was maintained for consumption of chocolate as a beverage. In Colmenero’s recipe, the ratio of nuts to other solids (prior to combining with water to make it drinkable) is less than 1:10.

In other words, with respect to the nuts, Colmenero does not claim what Cagliano thinks he claims. Further still, Colmenero’s elaborate chocolate beverage—which contains more anise than nuts, in addition to chiles, vanilla, cinnamon, achiote, ear flower, and mecaxochitl (which wasn’t as easy to find in seventeenth century European markets as you might think)—could hardly be considered a conceptual antecedent of gianduia. On this issue, as on others, Cagliano proves unreliable.

(6) Cagliano [February 1932], 52.

(7) As we will see in a subsequent discussion, some of Cagliano’s mistakes offer clues as to the source of his information.

(8) Aindardi, 56.

(9) This inconsistency between the 1852 narrative and the date of Prochet’s birth was perspicaciously noted by the Padovanis in their recent work, Gianduiotto Mania — La Via Italiana al Cioccolato: Storia, Fortuna, Ricette. Giunti, 2007. P. 54.

(10) The absence of any contemporary written evidence for the existence of gianduia (or a gianduia-like substance) in the 1850s is even more problematic than the prior silence (e.g., during the years of the Continental System), due to the abundance of print media in Turin in the decade following King Carlo Alberto’s expansion of press freedom in 1847.