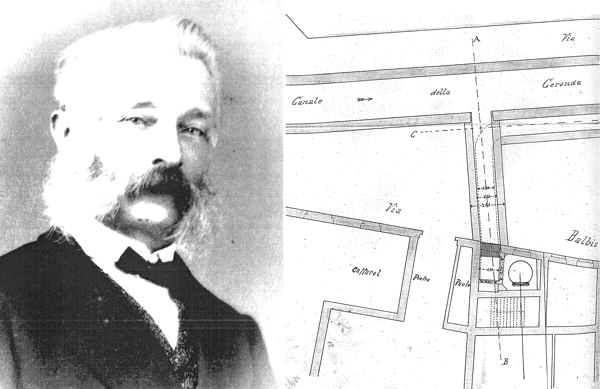

Following the 1837 death of the Bleniese inventor Giovanni Martino Bianchini, Paul Caffarel (pictured above) continued to manufacture chocolate using the same machine Bianchini had installed in the Watzenborns’ converted tannery. He was to be the first of a wave of Waldensian chocolate makers in Turin. Because of the Waldenses’ importance in the rise of gianduia, we will briefly introduce some of the key individuals and companies that will figure into the story ahead.

Guida Commerciale Marzorati-Paravia di Torino, 1842

The Guida Commerciale of Turin of 1842 (the first published after Bianchini’s death) listed most chocolate makers in the city simply by name and address. Cafferel was listed with greater detail than his contemporaries, due to the novelty of mechanization: “Caffarelli, Father and Son, Manufacturers of Chocolate by Means of Hydraulic Machinery, by Privilege of His Majesty” (1). Caffarel retained this distinction until the 1851 Guida, when Giuseppe Risso was also listed as a “Manufacturer of Chocolate by Machine” (2). The use of water- and steam-powered equipment quickly became both a competitive necessity and a selling point for chocolate makers in Turin, featuring prominently in directory listings and advertisements.

Talmone advertisement, 1896

The 1859 Guida introduced another influential Waldensian chocolate maker, Michele Talmone (3)(4). Talmone, a native of the Waldensian community of Villar Pellice (in Val Pellice), began his own business in 1850, possibly after leaving the employ of Paul Caffarel (5). His 1,500 square meter factory on Via Balbis was located a block away from Caffarel’s in Borgo San Donato and also derived waterpower from the Bealera di Torino (6). Talmone’s company would later become an early promoter of gianduia, a trend-setter in marketing, and the largest chocolate-making company in Turin (7).

Guida Commerciale di Torino, 1866

Another Waldensian company that played a major role in the history of gianduia appeared in the 1866 Guida, Prochet, Gay & Co. The company was owned by three Waldenses, Michele Prochet, Jean Henri Gay, and Barthelemy Revel (8). Prochet was born in San Giovanni Pellice, the Waldensian valley community that had previously been home to the Watzenborns and Caffarel (9). His factory was located on Piazza Statuto, a short distance from those of Caffarel and Talmone, also drawing waterpower from the Canal of Turin (10). Prochet’s skill and creativity were quickly recognized with a medal at the 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris (11). Prochet, Gay & Co. lasted little more than a decade (leaving the new company Gay & Revel). However, as we shall see, Michele Prochet continued to impact Turin’s chocolate industry into the early years of the twentieth century.

Moriondo & Gariglio advertisement in the Gazzetta del Popolo, 1869

As Borgo San Donato became the center of Turin’s chocolate industry, makers jockeyed for expansion rights and for additional water power. Responding to industrial demand, the city completed the Ceronda Canal in 1869, and several chocolate makers, including Caffarel, Talmone, and Prochet, Gay & Co., applied for power from the canal’s right branch (12). One key maker to gain water rights on the Ceronda Canal was Moriondo & Gariglio, a partnership of Agostino Moriondo and Francesco Gariglio. Though not Waldenses, Moriondo & Gariglio became a market leader by the end of the century, rivaling Talmone in size and with a reputation for quality gianduiotti.

The sudden rise of the Waldenses in Turin’s chocolate industry may seem improbable, given the institutional obstacles they faced due to their faith. However, they did possess some advantages. First, in the mid-nineteenth century, industrial chocolate-making remained an essentially open field, since most Turinese makers were still grinding by hand. The overwhelming economic advantages of mechanization allowed for swift dominance of the market.

Second, political and ecclesiastical persecution in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had pushed Waldenses by the tens of thousands into France and western Switzerland, areas with robust chocolate cultures. The Glorious Return and subsequent resettlement brought some of that culture (and probably technology) back to the Waldensian valleys of Piedmont (13).

Ruins of the Fort of Mirabouc, Val Pellice (from The Waldenses; William Beattie, 1836)

Third, and most crucially, centuries of persecution forced the Waldenses to develop a deep communal cohesiveness. What had been a survival mechanism in the mountains became a reflexive business strategy in the city. Though the Waldensian entrepreneurs were competitors, they were often family. Some business/family relationships were generational and others sibling, but many were by marriage.

As previously mentioned, shortly after Paul Caffarel purchased the Watzenborn mill, he gave his daughter’s hand in marriage to Jean Jacques Watzenborn (14). Michele Prochet’s brother, Matteo, married Milca Caffarel, daughter of Pierre Paul Caffarel (son of Paul Caffarel) and Olympe Gay (15). Michele himself was married to the daughter of Jean Jacques Revel. The following decade, Michele Prochet joined Ernesto and Pierre Paul Caffarel to form Caffarel Prochet & Co. (16). Michele Talmone’s wife was from the same line (Gonin) as Marie Madeleine Watzenborn (17). The Waldensian family Malan appeared, by marriage, in the lines of Matteo Prochet, Michele Talmone, and Walter Bächstädt (who took the helm of Caffarel Prochet & Co. in the early 1930s) (18).

The dizzying cycle of connections demonstrates that, for nearly a half century after moving into Turin, Waldensian chocolate-makers retained a significant measure of social cohesion, whether by deliberate choice or external marginalizing forces.

The closing decades of the nineteenth century saw the rise of other significant chocolate companies, both Waldensian (e.g., Rostan) and non-Waldensian (e.g., Baratti & Milano, Silvano Venchi) (13). However, there’s no need to discuss them at this point, since they arrived on the scene after the birth of gianduia.

Notes:

1. As previously noted, many Waldenses living in Turin Italianized their names in an effort to avoid persecution and discrimination, as well as to make their names pronounceable to Piedmontese and Italian speakers. Paul Caffarel became Paolo Caffarelli.

2. Ainardi, Mauro Silvio and Paolo Brunati. Le Fabbriche da Cioccolata: Nasscita e Sviluppo di un’Industria Lungo i Canali di Torino. Umberto Allemandi & C., 2008. P. 53.

3. Ainardi, 55.

4. Talmone is Italianized from the Waldensian surname Talmon. (See note 1.)

5. Ainardi, 1, 82. Uncharacteristically, Ainardi does not cite his source for the claim that Talmone worked for Caffarel. Elsewhere in the same book, Paolo Brunati writes that Talmone opened his shop after returning from Switzerland, where he had studied chocolate making, probably based on a similar story in Enrico Gianeri’s Storia di Torino Industriale: Il Miracolo della Ceronda (p. 104). Ainardi’s work in the book is meticulous and based on primary and archival materials (particularly from the Archivio Storico della Città di Torino and Archivio di Stato di Torino), but more specific information is needed to support this claim. Christian Bächstädt-Malan fails to mention any employment relationship with Talmone in his well-researched dissertation on Caffarel.

6. Ainardi (Brunati), 104.

7. Annali di Statistica: Statistica Industriale, Fascicolo XVII, Notizie sulle Condizioni Industriali della Provincia di Torino. Ministero di Agricoltura, Industria e Commercio. Direzione Generale della Statistica. Tipografia Eredi Botta. Rome. 1889. P. 72.

8. Ainardi, 82.

9. Michele Prochet’s brother, Matteo, was a prominent, highly visible member of the community in his role of Chairman of the Board of Evangelization. Rostan, Rev. Francesco. “Com. Matteo Prochet of Italy: An Appreciation,” in The Missionary Review of the World, Vol XX., No. 9 (New Series), September 1901. Pp. 685-6.

10. This concentration of factories made Borgo San Donato the heart of Turin’s chocolate industry until growth, competition, and the availability of additional waterpower along the Ceronda Canal pushed development in different directions.

11. Ainardi, 81.

12. Ainardi, 17.

13. Bächstädt-Malan Camusso, Christian. Per Una Storia dell’Industria Dolciaria Torinese: il Caso Caffarel. Doctoral thesis (Economics and Business), Universitá degli Studi di Torino. 2002. P. 63.

14. “Focus on Gianduia, Part 7: Swiss Chocolate in Early Nineteenth Century Turin,” Note 13.

15. “Michel Prochet” (pedigree chart), Archivio Tavola Valdese, Fondazione Centro Culturale Valdese. Torre Pellice. 2007.

16. Bächstädt-Malan, 86.

17. “Watzenborn” (pedigree chart), Archivio Tavola Valdese, Fondazione Centro Culturale Valdese. Torre Pellice. Also, Talmone family grave site in the Cimitero Monumentale di Torino.

18. “Michel Prochet” (pedigree chart), Archivio Tavola Valdese, Fondazione Centro Culturale Valdese. Torre Pellice. 2007. Also, Bächstädt-Malan, Tables 6-9. Also, Talmone family grave site in the Cimitero Monumentale di Torino.