Having discussed the traditional tripartite composition of gianduiotti (i.e., sugar, cacao, Tonda Gentile delle Langhe), we now turn to their shape and three methods of formation.

Gianduiotti from Barbero (Cherasco).

According to the 1899 statement from Caffarel Prochet & Co., gianduiotti were originally sold as givo, the Piedmontese word for a May bug or, figuratively, a cigar butt (1). This presumably reflected the stubby shape of the product. Nineteenth century references to gianduiotti rarely describe a specific shape, though irregularity is sometimes noted, as in an 1883 dictionary referring to them as “small balls or morsels…of irregular form” (2).

Eventually, gianduiotti became standardized and took on the now-canonical form, which many Italian writers have described as a citrus wedge or an overturned boat. Paucity of historical evidence makes it impossible to pinpoint when this happened, though it seems likely that the familiar shape became universal in the late nineteenth century, with the growth of firms such as Talmone and Moriondo & Gariglio, both of which were known for the quality of their gianduiotti. Print photos survive of Moriondo & Gariglio’s molding and wrapping room, in which dozens of women sat before marble tables fashioning and wrapping gianduiotti by hand (3). Extant gianduiotti molds from the first decade of the twentieth century also bear the characteristic shape (4). With the rise of mechanized formation of gianduiotti in the twentieth century, the early diversity and irregularity of shape were further reduced.

The distinctive shape of gianduiotti derives from their composition. The fat content of Tonda Gentile delle Langhe hazelnuts generally ranges from 62-65% (5). Of that, over 90% consists of unsaturated fatty acids, which are liquid at room temperature (6). (The liquid fat content is noticeable simply by spinning some hazelnuts in a food processor, as seen below.) The high unsaturated fat content of nineteenth century gianduia paste made it soft and tacky—difficult to mold with any definition (and without mess).

Hand-cutting gianduiotti at A. Giordano (Leinì).

Most writers on gianduiotti agree that the earliest method for making gianduiotti involved tabling the gianduia paste with palette knives, cutting off bite-sized pieces, and depositing them on a chilled plate or marble slab to firm up, before being wrapped by hand (7). Some historical evidence seems to support this theory. Ainardi refers to an 1898 Exposition description of “a group of workers intent on cutting gianduiotti” in the factory of Moriondo & Gariglio, and an 1884 description of Moriondo & Gariglio workers making gianduiotti by hand (8).

Moriondo & Gariglio workers cutting gianduiotti in 1898 (Ainardi, 12).

In 1929, when the National Fascist Federation of Confectionery Industry worked with the Touring Club Italiano to compile the Guida Gastronomica d’Italia, the Federation’s submission on gianduiotto stated that “its characteristic, true, and original form is obtained solely by the hand-crafting of workers of special ability” (9). Hand-cut gianduiotti tend to be less precisely shaped, moister, even slightly sticky to the touch. (The hand-cut gianduiotti pictured at the top of this article are from Gerla in Turin.)

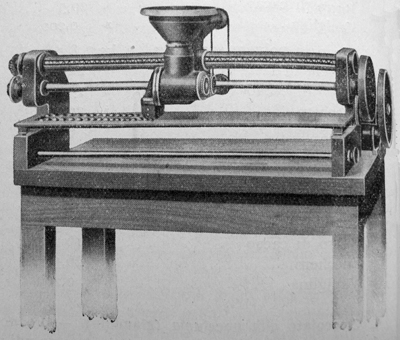

Carle & Montanari gianduiotti extruder (Kemeny, 1949).

The second common method for making gianduiotti is extrusion (10). Italians had long been familiar with extrusion, in both pastry and pasta secca (11). In the early decades after the invention of gianduia, shops extruded gianduia manually, with pastry bags or syringes. In 1907, a 23-year-old ex-Fiat mechanic invented the first motorized gianduiotti extruder (12).

Extruded gianduiotti by Gertosio (Turin).

Though other mechanical extruders also hit the market by the 1920s (e.g., Enrico Battaggion), they were used only by larger makers. Smaller makers in Turin continued to rely on metal pastry syringes (13). Extruded gianduiotti are more uniform and symmetrical in shape than hand-cut, usually slightly firmer, have smoother sides, and come to a sharp edge at the crest.

Molded gianduiotti from Peyrano (Turin).

The third common method is molding (14). Molding of chocolate products was common enough in the late nineteenth century that efforts to mold gianduia paste were inevitable.

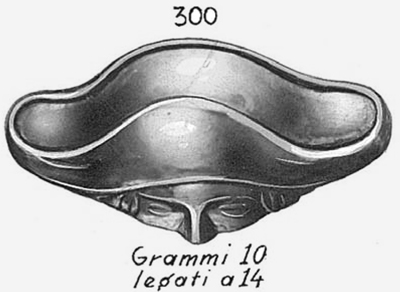

Gianduiotto molds (Sartorio, 1930).

However, as previously discussed, the hazelnut content of the earliest gianduia paste rendered it soft and sticky, unsuitable for molding. Molding could only become commercially practicable by increasing the percentage of saturated fat—most economically, by adding cocoa butter. Since the market for cocoa butter (as a byproduct of cocoa powder production for beverage use) only arose after the spread of the Van Houten press and “dutching” in the decades following the emergence of gianduiotti, molding of gianduiotti was not common among chocolate makers in the 1860s and 1870s.

Hinged gianduiotto molds circa 1910 (Caffarel, 252).

Metal molds for gianduiotti became more common in the twentieth century. Some of the earliest extant molds (from 1910) allow two halves of the mold to be opened on a hinge, implying a texture still too tacky to be easily released (15). By the 1920s, many small makers made gianduiotti with metal molds, individually and in sheets (16). One 1930 catalog features a collection of stainless steel gianduiotto molds of varying sizes and shapes, including a fanciful depiction of Gianduia’s hat that approximates the traditional gianduiotto form (17).

Gianduia-shaped gianduiotto mold (Sartorio, 1930).

By the latter half of the twentieth century, the economical advantages of mechanical molding made this the most common method, particularly among industrial makers. Molded gianduiotti are, of course, the most uniform in size and shape, usually firmer than hand-cut or extruded pieces, smoother and glossier in finish (due to higher cocoa butter content), and rounded at the top edge (to release more easily from the molds).

Hand-cutting, extrusion, and molding are all capable of producing gianduiotti with the traditional wedge shape. However, from the connoisseur’s perspective, the methods are not equally favored—a point to which we will return.

Notes:

1. Caffarel S.p.A (ed.). Caffarel, 170 Anni: Avanti, Sempre Più Avanti (La Meravigliosa Storia del “Cioccolato d’Autore”). Caffarel S.p.A. 1996. P. 254.

2. Fanfani, Pietro & Giuseppe Frizzi. Nuovo Vocabolario Metodico della Lingua Italiana, P. I. Libreria d’Educazione e d’Istruzione. Milan. 1883. P. 841.

3. Ainardi, Mauro Silvio and Paolo Brunati. Le Fabbriche da Cioccolata: Nasscita e Sviluppo di un’Industria Lungo i Canali di Torino. Umberto Allemandi & C., 2008. Pp. 85, 87.

4. Caffarel, 252.

5. Ebrahem, K.S., D.G. Richardson, R.M. Tetley, and S.A. Mehlenbacher. “Oil Content, Fatty Acid Composition, and Vitamin E Concentration of 17 Hazelnut Varieties, Compared to Other Types of Nuts and Oil Seeds,” Proceedings of the III International Congress on Hazelnut. Acta Horticulturae: 351. 1992.

6. Valentini, N., G. Zeppa, L. Rolle, and G. Me. “Caratterizzazione Chimico-Fisica e Sensoriale delle Nocciola Tonda Gentile delle Langhe.” 2° Convegno Nazionale sul Nocciolo. Giffoni Valle Piana. 2002. P. 284.

7. Marsero, Mario. Dolci, Delizie Subalpine: Piccola Storia dell’Arte Dolciaria a Torino e in Piemonte. Lindau. Turin. 1995. P. 75. See also, Ainardi & Brunati, 109. See also, Padovani, Clara Vada and Gigi Padovani. Gianduiotto Mania — La Via Italiana al Cioccolato: Storia, Fortuna, Ricette. Giunti, 2007. Pp. 76-7.

8. Ainardi, 89, 93.

9. Il Dolce, No. 42, August 1929. P. 196.

10. Marsero, Mario. “Gianduia: Storia di un Cioccolato,” Pasticceria Internazionale, n. 141. 2000. P. 141. Padovani & Padovani, 80-1.

11. Screw-presses for dry pasta were in use in Naples in the early seventeenth century and gradually spread. (Dickie, John. Delizia! The Epic History of the Italians and their Food. Sceptre. 2007. Pp. 161-3.) Though fresh pasta has always prevailed in Piedmont (e.g., tajarin and agnolotti), pasta secca was not unknown and became even more common after unification. For syringe extrusion in pastry, see Il Confetturiere Piemontese, che Insegna la Maniera di Confettare Frutti in Diverse Maniere. Beltramo. Turin. 1790. Pp. 14, 16, 64.

12. “The Manufacturing Confectioner.” Vol. 87, No. 10. October 2007. P. 98. The inventor, Enrico Carle, later moved to Milan, formed Carle & Montenari, and became a major manufacturer of chocolate equipment (today under the control of SACMI).

13. Spagnoli, Mario. Fabbricazione del Cioccolato. Ulrico Hoepli. Milan. 1926. Pp. 114-5.

14. Marsero [2000], 141. Padovani & Padovani, 78-9.

15. Caffarel, 252.

16. Spagnoli, 115. Spagnoli approves of the use of molding, since it results in uniformly sized pieces that work well with mechanical wrapping devices.

17. Fabbrica Italiana Lavorazione Stampi C. Sartorio. “Catalogo N. 2. Stampi per Cioccolato in Acciaio Inossidabile.” Turin. 1930.