To this point, we’ve discussed the pre-history of gianduia up to the 1850s. Now, let’s step back and look at the origin of Gianduia, the commedia dell’arte mask and namesake of gianduia and gianduiotti. The traditional origin story of Gianduia, the mask, begins with two puppeteers, Giambattista Sales and Gioachino Bellone (1).

In the closing years of the eighteenth century, Turin’s Piazza Castello often had a circus atmosphere, with performers and salesman of every kind busking and hustling. One such entertainer was Umberto Biancamano (stage name: Giôanin d’ij ôsei), a noted puppeteer who popularized Gironi, a puppet with a tricorn hat, a brown tailcoat trimmed in red, a ruddy complexion, and a fondness for wine (2).

The young Giambattista Sales attended and studied Biancamano’s performances. Inspired by the master, Sales began putting on his own shows in the courtyard of his house, with a stage improvised from crates. Recognizing the difficulty of competing with established acts in Turin, Sales teamed up with Gioachino Bellone, obtained a portable stage, and began a tour of the regions south and east. To appeal to a wider audience, the pair Italianized the Piedmontese “Gironi” to “Gerolamo.”

Piazza Castello (Turin)

After stops in Testona, Pessione, and Felizzano, Sales and Bellone arrived in Genoa. Genovese audiences responded to the puppet Gerolamo with special enthusiasm. The young puppeteers were probably unaware that Gerolamo Durazzo was the Doge of the Ligurian Republic and, following French annexation, a Senator and Count of the Empire (3). The local authorities regarded the puppet’s buffoonery as treasonous and promptly issued a decree expelling Sales and Bellone from the territory (4).

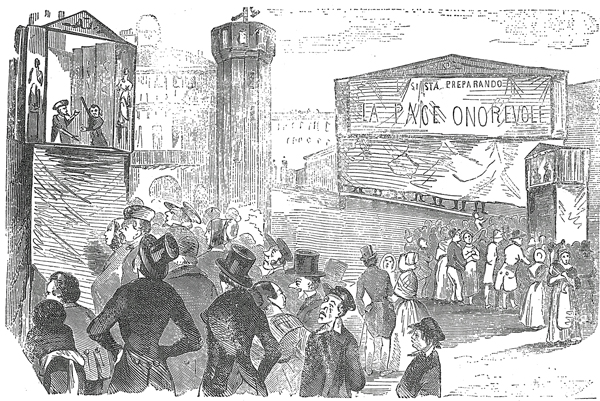

Upon returning to Turin, the puppeteers began performing their new routines, locating their stage a respectful distance from Piazza Castello, where Biancamano still operated. One night, they performed a comedy by Padre Ringhieri titled, “Artabano the First: The Tyrant of the World, with Gerolamo, his Confidant and King by Combination.” Some audience members sympathetic to Napoleon regarded the comedy as an attack on the Emperor and his younger brother Jérôme—or, in Italian, Girolamo—who had recently been made King of Westphalia. The police intervened and broke up the show. The puppeteers were charged with impersonating the King of Westphalia with a puppet and subjecting him to public ridicule (5). Treason again.

Gianduia (Marionette Lupi, Turin)

After being released from prison, Sales traveled to Callianetto, near Asti, where he resumed his performances. In 1808, Sales changed the puppet Gerolamo’s name to Gianduia. Though etymological speculation continues, the dominant theory is that Gianduia was a contraction of the Piedmontese “Giôan d’la dôja”—or “John of the jug,” referring to the earthenware bottle of Barbera carried by the puppet (6).

Sales refined the character of Gianduia, moving it away from its roots as Gironi and into something more distinctive of Piedmontese self-image—clever, brave, willful, independent, drily witty, and fond of good wine. Sales found a wife for the character (Giacômëtta) and provided him with a surname (Crinòira) (7).

Giacômëtta (Marionette Lupi, Turin)

On November 25, 1808, Sales presented Gianduia to Turin for the first time in “The Magic Ring, or The 99 Misfortunes of Gianduia.” The show was well received by audience members, regardless of political affiliation; and the police, while present, saw no need to take any action, since there was no mention of Gerolamo. Once again, Sales and Bellone went on tour, even returning to Genoa without incident.

The pair returned to Turin in 1811 and rented Teatro Gallo as a permanent location for their shows. After several years of success, Sales and Bellone moved into the former Theater San Rocco in 1819, renaming it the Theater of Gianduia (8). The 1820s brought further popularity and expansion, with the establishment of Sales Circus in the southeast part of the city (9). The decade also saw the rapid evolution of Sales’s puppets into more finely controlled marionettes (10).

Though puppetry in Turin during the first half of the nineteenth century served primarily as entertainment, it also provided an outlet for political expression in a period of severely limited freedom of the press. The improvisational form offered censors a constantly, rapidly moving target. Puppeteers could prudently shape the performance, rousing the crowd by skewering an unpopular public figure or reining in the material to avoid provocation. Cloaking political comment in humor made it less obvious and objectionable to authorities. As further protection, Gianduia spoke Piedmontese, which would not be understood by French or Tuscan monoglots.

From these seeds, Gianduia’s full transformation from popular marionette to political symbol began in the late 1840s (11).

Notes:

1. Strafforello, Gustavo (ed.). La Patria: Geografia dell’Italia (Provincia di Torino). Second edition. Unione Tipografico-Editrice Torinese. 1907. P. 212.

2. Bianchi, Nicomede. Storia della Monarchia Piemontese dal 1773 sino al 1861. P. 240.

3. Bianchi, 240.

4. Gianeri, Enrico. Gianduja nella Storia, nella Satira. Famija Turineisa. Turin. 1962. P. 4. Gianeri has provided the most thorough treatment of Gianduia to date, though he tends to accentuate picaresque elements of the puppeteers’ biographies.

5. Gianeri, 5.

6. Battaglia, Salvatore. Grande Dizionario della Lingua Italiana (Volume VI, Fio – Grau). Unione Tipografico-Editrice Torinese. Turin. For Barbera as Gianduia’s wine of choice, see: Viriglio, Alberto. Torino e i Torinesi: Minuzie e Memorie. Andrea Viglongo & C., Editori. Turin. 1980 (original, 1898). P. 206. Alarni, Fulberto. Sonetti e Poesie Varie in Vernacolo Piemontese. F. Casanova, Editore. Turin. 1889. P. 137. Scotta, Cesare. Cansson Piemonteise Edite e Inedite d’ Cesare Scotta. Stamparia Nassional d’ Botero Luis. Turin. 1868. P. 183. Gianeri, pp. 3, 100.

7. Gianeri, 4, 8.

8. Molineri, G.C. (et al.). Torino. Roux e Favale. Turin. 1880. P. 487.

9. Gazzetta Piemontese, No. 37, March 27, 1830. P. 207.

10. Gianeri, 15-16. However, Molineri dates the transition to marionettes in 1845 (488).

11. In the video below: Marionette Lupi (Raoul Cristofoli and Daniela Trezzi), performing Cappuccetto Rosso (i.e., Little Red Riding Hood). Turin’s Gianduia Theater and Marionette Museum are descended from Luigi Lupi, a nineteenth century contemporary and rival of Sales, with whom Gioachino Bellone partnered in 1876 (Gianeri, 22-5). The marionettes in the video and pictured in the report above are the original nineteenth century wooden pieces used by the Lupi family, as are the hand-painted backdrops.

Of the Lupi marionettes, Susan Young writes, “The marionette of the Lupi are unrivaled in their beauty and meticulous attention to detail. The costumes and furnishings were made by skilled craftspeople and each marionetta possessed a complete wardrobe, including items which would never be seen by the audience. In this respect, the Lupi typify the almost obsessive quest for perfection in the staging which was a distinguishing feature of the most renowned marionettisti.” (Shakespeare Manipulated: The Use of the Dramatic Works of Shakespeare in ‘teatro di figura’ in Italy. Associated University Presses. 1996. P. 32.)